In Florida, a state senate committee wants to make it illegal to cause discomfort to white people. This bill, which reads like a scene from 1984, is a doozy. You can, and should, read the full text of it here.

The bill purports to “protect individual freedoms and prevent discrimination in the workplace and in public schools.” But it then proceeds to define “individual freedoms” and “discrimination” in ways that are unrecognizable to the plain, historic meaning of those words.

Here’s a quick tour. The bill notes that the State Board of Education (SBE) “requires that instruction on the required topics must be factual and objective, and may not suppress or distort significant historical events, such as the Holocaust, slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction, the civil rights movement and the contributions of women, African American and Hispanic people to our country.” So far so good.

But here are the next two sentences:

Examples of theories that distort historical events and are inconsistent with SBE-approved standards include the denial or minimization of the Holocaust, and the teaching of Critical Race Theory, meaning the theory that racism is not merely the product of prejudice, but that racism is embedded in American society and its legal systems in order to uphold the supremacy of white persons. Instruction may not utilize material from the 1619 Project and may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.

The magnitude of the contradictions here, separated only by a comma, is jarring. The minimization or denial of the Holocaust is prohibited, but the minimization and denial of America’s treatment of Native Americans and African Americans is mandated.

A critical reading of history has lessons for the Germans, but not, evidently, for Floridians. The systematic oppression and murder of Jews overseas holds lessons for today, but the bigotry and violence toward Native Americans and African Americans at home does not.

Never mind that Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime studied America’s treatment of Native Americans and African Americans in their search for models for subjugating and exterminating European Jews. Never mind that the Declaration of Independence’s “universal principles” include a description of Native Americans as “merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions.”

The most pernicious part of the bill is its bizarre definition of “individual freedom,” consisting of eight principles plainly written to protect white people. The final one is the most sweeping: “An individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.” The bill then proceeds to define “discrimination” under Florida state law as a violation of “individual freedom.”

This provision effectively gives any single white person veto power over the content of history curriculum in schools or trainings in the workplace. White discomfort governs historical truth.

As I noted in October (“Shutting Down the Manufactured Critical Race Theory ‘Debate’”), this bill shares a common purpose with the raft of other CRT bills emerging in state legislatures across the country. These bills are political theatre and campaign tools dressed up in the guise of legislation. There simply is no evidence that the problem these bills purport to address—a widespread use of CRT in primary and secondary education settings—exists.

It’s easy to dismiss all of this. But the conjuring of discomfort avoidance as a mark of individual freedom and thereby the grounds of a novel conception of discrimination is revealing.

First, we should answer the question, “Why are we seeing this strategy emerge now?” According to a study by The Brookings Institution, as of November 2021, 9 states had passed, and 20 states had introduced bills that are being promoted as banning CRT.

Part of the answer lies in the unique cultural moment we are inhabiting as a country. As I argued in my 2016 book, The End of White Christian America, the visceral nature of today’s white conservative politics is driven by its desperate need for new mechanisms for ensuring white supremacy amid America’s changing demographics, particularly the loss of a white Christian majority over the last decade. As recently as 2008, white Christians comprised 54% of the population, but that number is 44% today.

More immediately, this legislation lifts language directly from former President Trump’s executive order targeting CRT, which banned the use of so-called “divisive concepts” and introduced the white “discomfort” criteria. Biden repealed this executive order on his first day in office. The Florida bill, like the other bills, are part of a coordinated Frankenstein-style strategy for exhuming and resurrecting Trump’s defunct executive order.

However absurd the premise, the language merits further interrogation.

READ: Unlearning the Gospel of Whiteness

What does it mean to say that the avoidance of discomfort, particularly by those who represent the country’s historically dominant race and religion, is constitutive of individual liberty? And what does it reveal about the health and mindset of white Christians today?1

Let me start with an easy analogy.

What if this bill included the avoidance of individual discomfort not just to Florida’s teachers but to Florida’s athletic coaches? Florida, like most southern states, is obsessed with football. But what kind of football teams would Florida schools produce if players could argue that they were being discriminated against if they were made to feel uncomfortable?

When I was younger, I had dreams of playing soccer at the highest levels. I participated in the Junior Olympic development program, made the high school all-star team for my state, and played Division III NCAA soccer for my Baptist college. Essential to my development as an athlete were coaches who were willing to address both mental and physical conditioning. At the end of a hard practice, One of my most demanding coaches would say, “It’s time to run.” If anyone dared to ask, “How many laps?” or “How long?” his regular response was, “Until I get tired.” Those practices often meant painfully pushing through a wall of fatigue with no end in sight.

My best coaches also relentlessly pointed out my individual shortcomings: tactical mistakes, sloppy play, insufficient leadership, and inadequate strategic compensation for my slight 5’6” 130-pound frame. These criticisms often angered me and certainly made me feel uncomfortable or embarrassed in front of my teammates. But they were necessary for motivating me to be a better athlete.

Spurred by the pandemic, I’ve taken up cycling. As I’ve been inducted into cycling culture, I’ve been surprised to find that the word “suffering” is common parlance. You hear it from amateurs in training and from commentators at the Tour de France. One of the most popular indoor training apps until recently went by the enticing name, “SufferFest.” The accepted wisdom is simple: Victory often goes to the competitors who have befriended suffering, those who can keep the cranks turning even when their quadriceps burn and their lungs feel as if they are about to explode.

At the elite level of sports, where everyone has talent, the winning edge is often the willingness to endure to the far edge of tolerable pain—because discomfort, even extreme discomfort, builds resilience and strength and prepares one for achievement when it matters.

Here’s another analogy, closer to the mark.

What if this metric were applied not just to teachers we entrust with educating our children but to parents? What kind of children would we have if we never wanted them to feel discomfort? Every parent wants to protect their children from pain. But we intuitively know that some forms of discomfort, such as feeling bad about ourselves when we’ve done something wrong, helps us assume responsibility for our mistakes and spurs us to make things right. Sitting with, owning this kind of discomfort is an essential part of forming a strong moral core and becoming a mature adult. Without that unpleasant psychological experience, a person becomes a sociopath, someone who has an inability to care about the feelings or needs of others—someone who lacks a sense of moral conscience.

Discomfort and moral responsibility are also linked in the work we face as descendants. Some of us find ourselves the beneficiaries of intact, generally functioning families that go back generations. But many of us find it necessary to reckon with disfunction, abuse, addiction, bigotry, and other unpleasant family inheritances. There are parts of our heritage we do not want to pass on. In those cases, only by facing these uncomfortable truths do we find the courage to declare, as my parents thankfully did with racial prejudice, that those destructive legacies stop with us.

Finally, what about the role of discomfort in Christian theology? This topic is particularly important, since most of those supporting these anti-CRT bills also wear their conservative brand of Christianity on their sleeves.

Particularly in white evangelical circles, discomfort is central to both salvation and discipleship. In traditional revival meetings, the experience of discomfort was even institutionalized, represented by the “mourner’s bench”—also tellingly called the “anxious bench”—where those wrestling with a newfound conviction of their sins would visibly struggle in prayer, often crying out or wailing as the reality came crashing into their consciousness.

The beloved hymn, “Amazing Grace,” captures this dynamic. In the very first stanza, a Christian singing that hymn identifies as “a wretch” in need of salvation. The familiar refrains—“I once was lost, but now I’m found/Was blind but now I see”—begin with lament and confession. Grace is amazing precisely because God accepts us despite our own shortcomings. But we don’t come to salvation, nor do we grow in discipleship, without honesty and this experience of exquisite discomfort.

Moreover, the sacred role of discomfort is not limited to sin in individual hearts. The Bible is replete with language about the sins of one generation being visited down three or four generations (Exodus 20; Numbers 14; Deuteronomy 5; Jeremiah 32). This transmission is not mystical but is both genetic and cultural. Just as abuse begets abuse and addiction begets addiction, prejudice begets prejudice.

In the New Testament, Paul talks about the need to reckon not just with sinful individual nature but with “principalities and powers,” a theological way of describing the impersonal, menacing aspects of cultural and institutional power.

In White Too Long, I summarized some remarkable research demonstrating these effects playing out among southern whites by political scientists Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen:2

Whites residing in areas that had the highest levels of slavery in 1860 demonstrate significantly different attitudes today than whites who reside in areas that had lower historical levels of slavery: 1) they are more politically conservative and Republican leaning; 2) they are more opposed to affirmative action; and 3) they score higher on questions measuring racial resentment. After accounting for a range of other explanations and possible intervening variables, Acharya and his colleagues conclude that “present-day regional differences, then, are the direct, downstream consequences of the slaveholding history of these areas.”

In my own family’s history, I’ve seen these dynamics play out, particularly in two moments of revelation. The first was realizing that my extended family’s Christian denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, was explicitly founded in 1845 as a place where the gospel of Jesus Christ could coexist with the practice of race-based chattel slavery.

The second came just five years ago. While doing research for White Too Long, I discovered the estate settlement records of my sixth great uncle and the namesake of my fifth great grandfather, Pleasant Moon, whose 1815 Bible rests on my bookshelf.

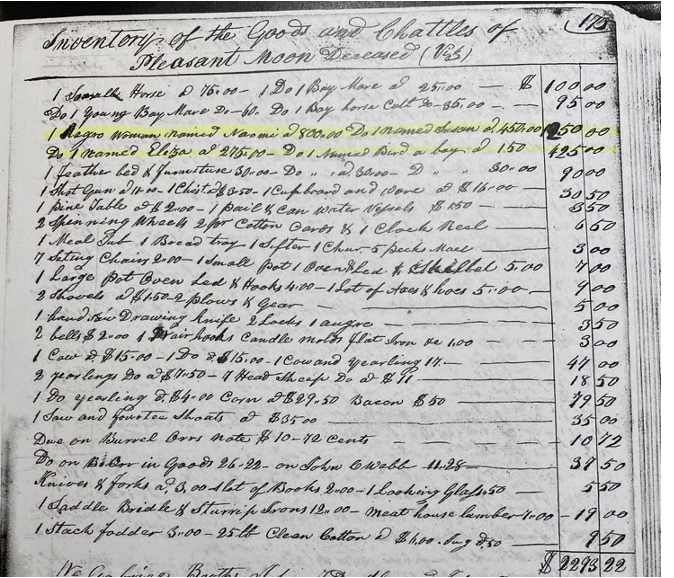

Inventory of the Goods and Chattles of Pleasant Moon Deceased (1815). From state of Georgia digitized archives.

Through the marvels of digital technology, this page moved from a leather bound book in the Twiggs County, Georgia, archives, to the printer in my living room. And then it was in my unsteady hands—an accounting ledger in which four human beings are intermixed with material objects such as a feather bed, a spinning wheel for cotton, and a cow. I ran my finger over these lines, first touching the name, then the monetary value assigned to the person:

1 negro woman name Naomi @ $800

1 named Susan @ $450

1 named Eliza @ $275

1 named Bird, a boy @ $150

I knew my family had been given land the U.S. government had forcibly taken from Native Americans, and I knew there were enslavers in the family tree. I knew that “my people,” even up through my parents’ generation, had benefited from Jim Crow segregation in Macon—with schools, libraries, parks, pools, theaters, jobs, and entire neighborhoods marked “for whites only.”

Still, holding this page in my hands alongside the old family Bible was disorienting. They seemed to hold equal weight. The straightforward pride and connection I had felt to the lineage of people inscribed in the births/marriages/deaths pages of our heirloom Bible became mixed with feelings of shock and shame. How could the same people in my family be reflected in both of these documents?

“Discomfort” is an impotent word to describe the strong emotions these dueling histories have generated in me. But wrestling with the truth of this difficult history has not been debilitating. It has been a source of personal and spiritual growth. And it has freed me from from the delusional fantasy of “goodness” we white Christians feel compelled to defend in every narrative about ourselves and our country.

Most importantly, holding a more truthful understanding of the history of my family, my faith, and my country has given me more agency, not less. The assertion in these anti-CRT bills that white people should not be made to feel uncomfortable because of their race presupposes that unpleasant truths are always debilitating. It also assumes that the inevitable result is that white people will simply feel bad for being white.

But these desperate measures fail to imagine the transforming alternative I discovered along this journey, and the only alternative that will allow us to live into the promise of a multiracial democracy. The discomfort didn’t make me feel bad for being white; it gave me the critical distance that enabled me to continue freeing myself from the power that whiteness has held over my family for generations.

If we white Christians can muster the courage to walk in its company, discomfort with our racial history can be a sacred and saving gift.

This article was originally published on Jones’ Substack #White Too Long.