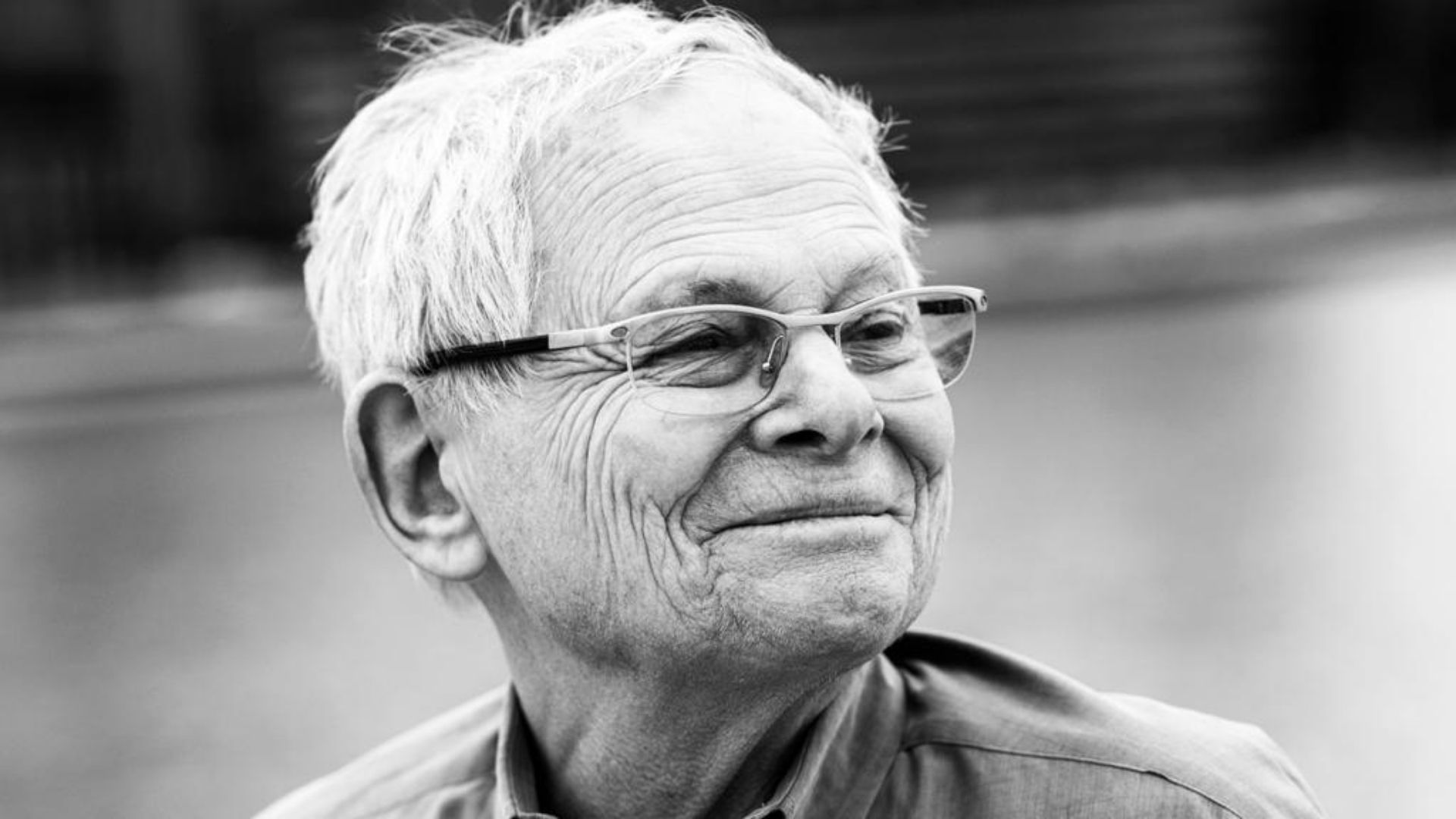

Last month, we lost a giant in the movement for a better world – Steve Schapiro. Some of you may not know him because he was usually behind a camera, capturing some of the iconic images of social changes, from the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war movement of the 60s right up until last year. I am humbled and honored to have had the chance to collaborate with Steve over the past few years. We had no idea it would be one of his last projects. I’ve also lost a friend, one of the most charming and interesting friends I’ve ever met.

He was an absolute legend. He was one of the kindest, grooviest people I’ve ever met (he liked the word “groovy”). We spent a lot of time together these last few years. I sure will miss him.

He was 87 and had been battling pancreatic cancer. He also just got baptized and was so at peace with everything. I talked to him on the phone a few days before he died. He smiled as he told me he would probably be dying soon, but everything was just fine. He was fearless and such an inspiration. He sent me the original photos he took of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. In fact, I have a whole box of his photos here in my office. They are like gold – better than gold – and I’ll post some of them from time to time.

One of the many memories I have is when I asked Steve curiously if he’d ever met Abbie Hoffman, one of most eccentric organizers of the anti-war movement in the 1960s, jailed along with seven others as part of the famous Chicago 8 trial. He smiled and said to me, “I photographed his wedding.” Of course he did.

Steve died last month on Martin Luther King’s birthday, January 15. Now he is with Dr. King in glory land. My heart goes out to his family, Maura, Theophilus, and all whose lives he touched.

Here’s a little more about the life of our brother Steve Schapiro:

Steve Schapiro discovered photography at the age of nine at summer camp. Excited by the camera’s potential, Schapiro spent the next decades prowling the streets of his native New York City trying to emulate the work of French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson, whom he greatly admired. His first formal education in photography came when he studied under the photojournalist W. Eugene Smith. Smith’s influence on Schapiro was far-reaching. He taught him the technical skills he needed to succeed as a photographer but also informed his personal outlook and worldview. Schapiro’s lifelong interest in social documentary and his consistently empathetic portrayal of his subjects is an outgrowth of his days spent with Smith and the development of a concerned humanistic approach to photography.

Beginning in 1961, Schapiro worked as a freelance photojournalist. His photographs appeared internationally in the pages and on the covers of magazines, including Life, Look, Time, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, Sports Illustrated, People and Paris Match. During the decade of the 1960s in America, called the “golden age in photojournalism,” Schapiro produced photo-essays on subjects as varied as narcotics addition, Easter in Harlem, the Apollo Theater, Haight-Ashbury, political protest, the presidential campaign of Robert Kennedy, poodles and presidents. A particularly poignant story about the lives of migrant workers in Arkansas, produced in 1961 for Jubilee and picked up by the New York Times Magazine, both informed readers about the migrant workers’ difficult living conditions and brought about tangible change—the installation of electricity in their camps.

An activist as well as a documentarian, Schapiro covered many stories related to the Civil Rights movement, including the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the push for voter registration, and the Selma to Montgomery march. Called by Life to Memphis after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Schapiro produced some of the most iconic images of that tragic event.

REGISTER: Race in America: A Conversation with Michael W. Waters on February 27th

In the 1970s, as picture magazines like Look folded, Schapiro shifted attention to film. With major motion picture companies as his clients, Schapiro produced advertising materials, publicity stills, and posters for films as varied as The Godfather, The Way We Were, Taxi Driver, Midnight Cowboy, Rambo, Risky Business, and Billy Madison. He also collaborated on projects with musicians, such as Barbra Streisand and David Bowie, for record covers and related art.

Schapiro’s photographs have been widely reproduced in magazines and books related to American cultural history from the 1960s forward, civil rights, and motion picture film. Monographs of Schapiro’s work include American Edge (2000); a book about the spirit of the turbulent decade of the 1960s in America, and Schapiro’s Heroes (2007), which offers long intimate profiles of ten iconic figures: Muhammad Ali, Andy Warhol, Martin Luther King Jr., Robert Kennedy, Ray Charles, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, James Baldwin, Samuel Beckett, Barbra Streisand and Truman Capote. Schapiro’s Heroes was the winner of an Art Directors Club Cube Award. Taschen released The Godfather Family Album: Photographs by Steve Schapiro in 2008, followed by Taxi Driver (2010), both initially in signed limited editions. This was followed by Then And Now (2012), Bliss about the changing hippie generation (2015), BOWIE (2016), Misericordia (2016), an amazing facility for people with developmental problems, and in 2017 books about Muhammad Ali and Taschen’s Lucie award-winning The Fire Next Time with James Baldwin’s text and Schapiro’s Civil Rights photos from 1963 to 1968.

Since the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s seminal 1969 exhibition, Harlem on my Mind, which included a number of his images, Schapiro’s photographs have appeared in museum and gallery exhibitions worldwide. The High Museum of Art’s Road to Freedom, which traveled widely in the United States, includes many of his photographs from the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King Jr. Recent one-man shows have been mounted in Los Angeles, London, Santa Fe, Amsterdam, Paris. And Berlin. Steve has had large museum retrospective exhibitions in the United States, Spain, Russia, and Germany.

Schapiro continues to work in a documentary vein. His recent series of photographs have been about India, music festivals, the Christian social activist Shane Claiborne, and Black Lives Matter.

In 2017, Schapiro won the Lucie Award for Achievement in Photojournalism. Schapiro’s work is represented in many private and public collections, including the Smithsonian Museum, the High Museum of Art, the New York Metropolitan Museum, and the Getty Museum.

I am grateful for Steve Schapiro – our friend and our brother. His images show us how the world is changed. They show us what courage and joy and resilience and defiant hope look like. I will miss him, but I am so thankful for every moment I have had with him. And as I think of the ear-to-ear smile he had when he told me he was dying, I am confident there is a party on the other side welcoming him home. I know he is smiling down on all of us now, alongside his friends John Lewis, Dr. King, James Baldwin, Rosa Parks, and the cloud of witnesses on whose shoulders we now stand.

Find more information at http://steveschapiro.com.