In his study “The lived experience of spiritual abuse,” David J. Ward makes a case for six common symptoms of spiritual abuse.

1. Leader Representing God—where leadership represents the highest spiritual authority, creates an atmosphere of forced immaturity among members and a culture of distrust for outsiders or naysayers

2. Spiritual Bullying—where ex-members are criminalized either overtly or subtly and members are robbed of the right to be themselves

3. Acceptance via Performance—where one’s worth is measured entirely on very specific productivity that serves the leadership and leadership’s vision

4. Spiritual Neglect—where an environment of omission is fostered, disallowing needs (emotional, physical, relational) to be met by outsiders if at all

5. Expanding External/Internal Tension—where dissonance between inner and outer realities continues to increase

6. Manifestation of Internal States—where that dissonance eventually substantiates through physical and mental maladies

Abuse is a big word. It is charged, laced with nuance, riddled with consequence, one way or another. Like the word trauma, we hear of it a lot these days. And as a writer, as a Christian, I am very careful about where I use them both, not because I think they are insignificant. But quite the opposite. I think they are words that represent grave realities deserving of our utmost responsibility, respect, and care. I enter into this record neither lightly nor rushed.

It quickens my breath to think about it. We were sitting in a circle comprised of my husband, my coworker, all of the executive leaders (older, male, white), and me. I’d anticipated some form of caucus would follow the letter I’d written and delivered at the end of the previous week, but the mental preparation hadn’t lessened my anxiety. It had taken me months to gather my thoughts and even longer my nerves.

For years in the environment of this employment, Matthew 18:15-17 had been drilled into me as the only appropriate (biblical) form of conflict management. (“If your brother or sister sins, go and point out their fault, just between the two of you.”) I was already breaking the rules by writing a letter, and to multiple people at that. But I had tried the face-to-face conversations, and those weren’t working. They left me muddled, interrupted, gas-lit, and embarrassed of my own emotions. If we were going to move forward relationally, professionally, socially, and spiritually (all areas of my life that had become intertwined within this work and community), then I had to share my truth in a way that allowed me both time to think and to speak.

READ: Silence: The Facilitator of Clergy Abuse

I had questions and concerns which were becoming increasingly impossible to ignore. Male employees under female directorship were being paid larger amounts; grant-funding wasn’t being delegated to the needs for which we’d written the grants; we were periodically being asked to go without paychecks (a reality that had been included as a possibility in our original contracts) and praised in the public square for our perseverance despite the sacrifice. Furthermore, protected always was a culture of optimism, and by that I mean, one devoid of challenge to those in power. To convey any of these issues as upsetting or inconvenient was to “sow a root of bitterness” into the otherwise content ministry body.

“You will never, ever accuse this leadership of sexism ever again. I won’t tolerate it,” the founder demanded with a wagging finger and harsh tone as we sat in my kitchen in the round, walking through my letter point by point. “I marched with women!” he scolded.

Today, it is darkly comedic, the irony of this moment. At the time, it was crushing. Who was I to propose such a thing? Had I witnessed any of what I thought I’d witnessed?

A few years before, we’d found each other (this faith-based nonprofit and I) at a time when I was most vulnerable—an ideologue in her early twenties deconstructing the capitalist nature of institutional Christianity and hungry for holistic, communal purpose. I was in transition or wanted to be, aching for mentoring and support. They were a light illuminating a different kind of path, a different kind of faith, and how it functioned in the real world.

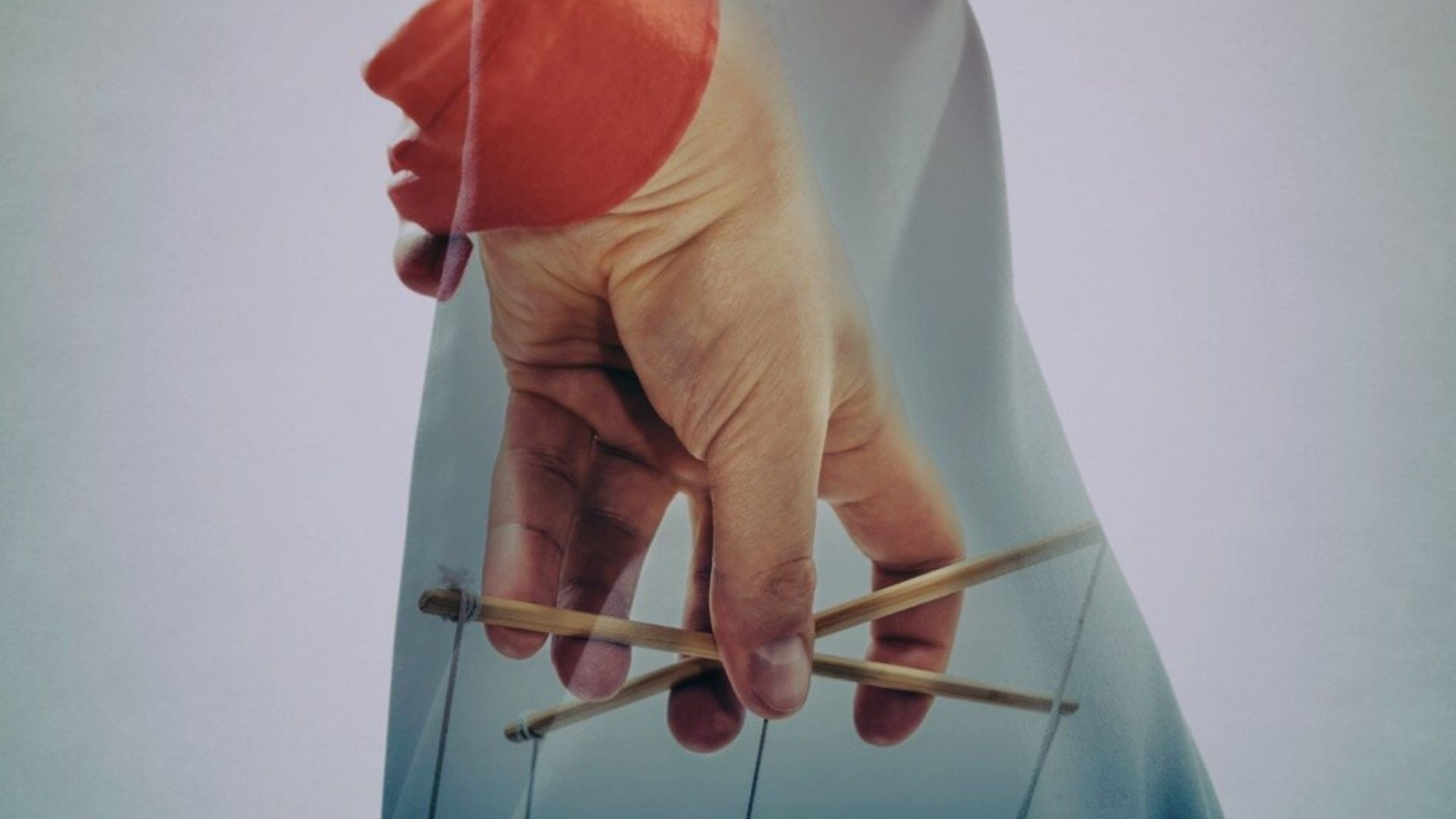

“I used to get up and go to work,” one of their second-career employees would say, “now I get up and come to life.” It was Utopian, this body of people whose careers and religions and friendships were all fed by the same source; I all but begged to be a part. So, I paid for inclusion with the currency of my ideas and network and became an extension of one person’s quest for their vision to be the one thing for all people. For years, I invited it into every part of my life, welcoming the entanglement, rehearsing the answers and systems of the lifestyle, cloning myself into a continuation of the leadership for whom I now represented hope for the organization’s future.

But there’s only so long you can survive with the internal dissonance of inner calling and outer manipulation.

The first writing workshop I was ever selected to attend during my tenure there should have been grand news to all those who cared for me. It was refining for my craft, encouraging for my vocational network, launching for my confidence, and threatening for my mentor. I sipped a La Croix on the couch of a monastic apartment, crafting an essay late into the night that would be workshopped at the next day’s round-table when my phone rang.

“I’m sorry to bother you so late, but the Holy Spirit has just told me to tell you not to sign anything. Do not sign anything while you’re there,” the urgent voice of my boss said.

Caught off-guard, I offered comfort, “There’s nothing to sign here. This is just a workshop. I’m learning from other writers.” When I hung up the phone, I noticed several texts had preceded the call: “DO NOT SIGN ANYTHING.” Upon returning to my city, I was whisked away to a lunch where I was told that the nonprofit would actually be starting a publishing house soon through which I could share all of my work. And that, if I so chose, of course, I could assign a percentage of the profits to the organization since most of my stories came from shared experiences within it anyway.

That was probably the first time I experienced a flag without the compulsion to coat it with internal excuses. Something was wrong, and now I could see it.

A breakdown ensued, first of my body; because a breakdown of my external reality would have meant the loss of everything. Every single part of my existence had been kneaded deeply into the milieu of the organization. To walk away from the work would equate to burning down my metaphorical house while I sat inside, weeping for what could have been. I thought maybe I would have a heart attack by age thirty, the stress was so consuming. But eventually, the cost of staying was at least equal to if not more than the cost of leaving. And, with much peace and gutting sorrow, I lit the match.

I’m told that my leaving, and therefore the total erasure of the program I and my friends had built, was excused by my eight-month-old child. She just couldn’t handle the work and motherhood.

Ward writes, “Spiritual abuse is a misuse of power in a spiritual context whereby spiritual authority is distorted to the detriment of those under its leadership. It is a multifaceted and multilayered experience that includes acts of commission and omission, aimed at producing conformity. It is both process and event, influencing one’s inner and outer worlds and has the potential to affect the biological, psychological, social and spiritual domains of the individual.”

With every year that passes since I began extricating my life and faith from the organization, I understand the experience with a little more clarity. But what colors most my evolving understanding is not an increased demonization of my former superiors, but rather a good, long look at how easy it was to become like them—to adopt a spiritual hierarchy, to mimic the enforcement of the rules onto those considered “under” me, to shame challenge and truth as “divisive.” Was I spiritually abused? Maybe you have an answer. Did I experience and further a culture of spiritual abuse? I’m willing to say yes.

Abused power is tricky when it comes wrapped in love and brilliance. We want so badly as people to be connected, to find the answer to all of our problems, to employ the systems that can fix everything when it feels like the world is burning. Because of this, especially if we’re vulnerable, it is easy (exciting even) to hitch our wagon to a wave of hope without the aid of critical thinking, no matter the cost.

But utopia and hell are just one refusing-to-be-challenged leader away from one another. It’s crucial to recognize this along with our susceptibilities as humans to jump headfirst into a persuasive person’s promise—especially those who fuel their influence and decisions with God, creating a manipulative atmosphere for those who wish to please God. And why is this important right now?

As a country, as a Church universal, we are in transition or want to be, aching for guidance and support. We are starved for a light to illuminate a different kind of path, a different kind of faith, and how it functions in the real world. We are vulnerable, but we cannot be desperate to the point of turning a neglectful eye to injustice wrapped in the language of faith. The result of this level of unchecked desperation can and has invoked the creation and perpetuation of silencing cultures, absolved maltreatment for the sake of “the cause,” and spawned trauma that is both deeply embedded and often unrecognizable to those stuck. We see this in the unwavering loyalty to political affiliations and the church’s countless sexual misconduct stories of #churchtoo.

But if the abuse of power is historically difficult to identify (and it often is, at least at first), how do we know what to look for? We need leaders who are willing to tell the truth, who—as Ward outlines—respect individual autonomy, tolerate and encourage critical thinking, recognize and are sensitive to power issues, accept the individual due to intrinsic human worth, seek to incorporate healthy bio/psycho/spiritual integration, and recognize and acknowledge their own personal flaws and limitations. And we need community members who are willing to invest in them rather than in the narcissistic megalomania of those who willingly trade integrity and humility for vision and power.

We need people who love the world more than they love themselves. Furthermore, we need people who love the world enough to not just better it but also release control over it. For to love your neighbor as yourself is to lay down your life, not enforce the duplication of it onto another.