Chapter 1: Life Is Good

Our goal is to develop a comprehensive, all-encompassing ethic of life that compels us to be champions of life, to cherish life, and to defend it passionately. To do that, we need a foundation on which we can build, and one we can keep coming back to. And where better to start than at the beginning, with creation itself?

Here’s how it all began, according to Genesis, the first book of the Bible. God took dirt and breathed life into it to make humanity. God created life and it was good.

It was good. That’s the refrain in Genesis 1 as God creates the world.

Over and over, like the chorus of a song, the Bible says, “It was good.”

God created the water. And it was good.

God created land and plants and trees and mountains and beaches. And it was good.

God created the moon and the sun and the stars in the sky. And it was good.

God created birds and fish and monkeys and butterflies and elephants and seahorses and the duck-billed platypus! And it was good.

Then God created humans in God’s own image. And God saw all that had been made and declared it very good. After that sixth day, when God made the first human beings and looked at the whole of creation in all its wonder, that’s when we get the addition of “very.” God’s creation wasn’t just good, it was real good. God was pumped. God was absolutely stoked.

And still is.

The Wonder Gap

Not many people are going to argue with the fact that life is good, but life is more than just good, it’s miraculous! And yet we tend to lose a sense of wonder at the miracle of it all. That’s why I love being around kids. They still have that sense of wonder.

Not long ago, I got a wonder wake-up call that started with a knock on my door. And it wasn’t just any knock, it was the frantic kind, the pounding kind, what some of the kids on my block call the “cop knock.” As I ran downstairs, I assumed there must have been an accident, a shooting, someone hit by a car, something bad. I took a deep breath to prepare myself for whatever might be next and opened the door. Standing there was eight-year-old Tysean, one of the neighborhood kids I’ve known since he was born. He grabbed my hand and began dragging me down the block. At this point, I could tell by his grin that it wasn’t something bad, not a shooting or a car wreck. But what was it?

“You’ve got to see this,” he said, pulling me like a dog on a leash. When we had gone about a hundred feet down the block, he pointed into the community garden. “What is that?” he asked. It was the first time he’d ever seen a firefly.

I thought for a moment and said the only thing I knew to say: “That was a really great day for God. God decided to make a bug whose butt glows in the dark.”

Author Paul Hawken notes that Ralph Waldo Emerson once considered what we would do if the stars came out only once every thousand years. Commenting on Emerson’s reflections, Hawken writes, “No one would sleep that night, of course. The world would become religious overnight. We would be ecstatic, delirious, made rapturous by the glory of God. Instead, the stars come out every night, and we watch television.”[1] Or maybe today we miss it all because we are watching Netflix or scrolling through our socials.

One of my friends is an astronomer named Dr. David Bradstreet. Before he was a friend, he was my astronomy professor at Eastern University. He wrote a whole book about the heavens titled Star Struck: Seeing the Creator in the Wonders of Our Cosmos. He starts by sharing how excited he was as a child every time he saw the stars. As he got older, he decided to study astronomy and eventually became one of the leading astronomers in the country. He even has a comet named after him. When you have a comet named after you, that’s beyond legit. Dr. Bradstreet is retired now, but he has never lost that sense of childlike wonder.

Some folks might suggest that the more you study the science of life, the less miraculous and wonder-full it seems. I know Christians who are scared of astronomy, fearful it might distract from the biblical narrative of creation. Others even see faith and science as opposing forces. But for Dr. Bradstreet, studying the science of creation has only increased his sense of wonder, deepened his faith, and further convinced him that there is a magnificent creator behind it all. All through his book, he drops spectacular facts, like the fact that the tail of Halley’s comet is sixty million miles long.[2] Or check this one out: every second, the sun converts four million tons of material into energy, the equivalent of ten billion nuclear bombs.[3] Fortunately, the sun is the perfect distance away and all that heat loses at least a third of its radiant energy in the eight-minute journey it takes to reach the earth.[4] If the earth were any closer to the sun, we’d burn up. If the earth were any farther away, we’d freeze.

Okay, one more. Every day, the divinely constructed and scientifically sound protective shield around the earth—the atmosphere—saves us from being hit by one hundred tons of small rocks and other pieces of space debris that would otherwise destroy the earth.[5] Amazing! Sometimes we miss the fact that life itself is a miracle. It may very well take more faith to believe that all of this life “just happens” than it does to believe that there is a divine creator behind it all.

Dr. Bradstreet has helped me appreciate Scriptures like this one: “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of [God’s] hands” (Ps. 19:1). And yet one of the questions Dr. Bradstreet raises is this: As the heavens cry out the glory of God, is anyone listening? He notes that some of his atheist peers in the scientific community have a deeper sense of wonder and awe about the universe than many of his Christian friends who are not scientists. He calls it the “wonder gap.”[6]

Too many of us have a wonder gap when it comes to the miracle of life in the natural world. That’s a problem because the more out of touch we are with the earth and the creatures of the earth, the easier it is to devalue or even destroy life.[7] When we are no longer awed by the miracle of creation, it gets harder to believe in the goodness and beauty of life—and the good and beautiful creator behind it all. That’s why gazing at fireflies and sunsets is a holy and spiritual practice. It not only fills us with wonder but also strengthens our foundation for life.

One of the ways we can bridge the wonder gap is by studying and contemplating how truly marvelous the world is. I’ve learned a lot about this from my wife, Katie Jo, who is one of the greatest nature lovers I’ve ever met. At one point, we had a spider who lived in the corner of the school-bus-turned-tiny-house we lived in for two years. When I went to remove it, she told me the spider’s name was Gladys and we needed to keep her because she ate the bad bugs, like stink bugs and mosquitos, so she was now a pet. Later, Gladys got pregnant and I finally talked Katie into putting her outside. Spiders can have up to a thousand babies, and that is too many pets for a tiny house.

Katie doesn’t have a wonder gap. She’s always telling me nature facts. For example, that the male seahorse is the one that gives birth. And that a hummingbird’s heart beats more than 1,200 times a minute and its wings flap sixty to eighty times a second. Katie is an aspiring beekeeper, and she taught me that bees have five eyes and that one hive can house around fifty thousand bees. Oh, and get this: the bees visit five million flowers to make one pint of honey. That makes you appreciate your honey, eh?

She’s always marveling at how the octopus changes color or that there is a flamingo that makes its nest out of salt. She just told me starlings can learn multiple bird languages or song patterns and speak them. And here’s a pigeon fact, which is important to know since pigeons can be challenging to love for those of us who live in the urban world. Even though they aren’t mammals, pigeons apparently have a milk reservoir in their crop—a section of the lower esophagus. Their “crop milk” contains antioxidants to keep their little ones from dying. Those are just a few Katie Jo wonder facts for you.

One of the wonders of the natural world that always amazes me is the complex emotional lives of animals. Did you ever see that viral video of the mother whale circling and crying out over her dead calf? Whales mourn, loudly and visibly, when another whale dies. How wild is that?

I was also amazed at a video taken at an elephant refuge, where a lot of old circus elephants are taken when they are rescued from abuse. The video shows a new arrival running up to another elephant and the two ecstatically wrapping their trunks around each other in an elephant hug of sorts. Refuge staffers later discovered that the two elephants had been in a circus together years before. How about that?

We need to recapture the childlike sense of wonder that kids so often have, because our lives are bound up with the beauty and flourishing of the natural world. We also need to pay attention to it because creation itself has a lot to teach us about who God is. The apostle Paul wrote, “Ever since the world was created, people have seen the earth and sky. Through everything God made, they can clearly see his invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature. So they have no excuse for not knowing God” (Rom. 1:20 NLT).

And when it comes to having a foundation for life, one of the most important things we can learn about God is revealed within the miraculous diversity of life.

The Miraculous Diversity of Life

Did you know that there are roughly ten million forms of life on the planet? Among other things, that includes more than 300,000 different plants, 1.25 million animals, 900,000 insects, 10,000 birds, and 8,000 reptiles.[8] Those numbers are even more astounding when you consider that 95 percent of the species that have ever existed on earth are now extinct. More specifically, one in eight birds, one in four mammals, and one in three amphibious creatures are now extinct. And we lose about one hundred species a day, which is twenty-seven thousand per year. Fortunately, we also discover several thousand new species of living creatures every year.

I learned a lot about the incredible diversity of life on earth when I visited my friend Claudio Oliver in Brazil. Claudio is part theologian, part veterinarian, and 100 percent nuts. He reminds me of the character Doc from Back to the Future—eccentric, wild, and full of passion and curiosity. When I visited, he woke me up at 5:00 a.m. and took me on an all-day adventure to show me what life is like running an urban homestead. We fed the rabbits, one of which would be dinner. We traded eggs for the milk of a neighbor’s cow. We went to the shopping mall, as Claudio denounced the evils of capitalism, to pick up used coffee grounds from the food court for his worm compost. Then he took me to the holy of holies, the “gene bank” where he is helping preserve endangered species of chickens.

“Do you know how many kinds of chickens there are?” he asked. Naturally, I started rattling them off like Bubba rattled off kinds of shrimp in Forrest Gump. “Well, there is fried chicken. There’s teriyaki chicken. Barbeque chicken. Chicken kababs.”

“No, no!” Claudio belted out with a laugh. “How many types of chickens?”

I had no idea, so I kept going. “Chicken curry. Sweet and sour chicken. . . .”

And then he told me that there are more than four hundred kinds of chickens—species of chickens, that is. Heck, he added, there are also forty thousand different kinds of rice. And apparently twenty-nine thousand different fish. Then Claudio got on his biodiversity soapbox and brought it all home: “Monoculture is diabolical. Diversity is divine.” He smiled and kept saying it louder and louder. “Monoculture is diabolical, but diversity is divine!”

Diversity is divine.

And diversity isn’t limited to plants and animals. Did you know that human beings speak more than seven thousand living languages in the nearly two hundred countries of the world?[9] Not to mention that each human being has a unique fingerprint. Each of us also has our own DNA that is distinct from the other eight billion people on the planet.[10]

If my friend Claudio’s theory sounds a bit out there to you, let me take you on a little Bible adventure to unpack this idea of monoculture and diversity. Think back to the Old Testament story of the Tower of Babel, one of the first major projects of human beings (Genesis 11). As the story goes, the whole human race was the same. There was one language, one culture, and the people were pretty impressed with themselves. They began an ambitious building project to bridge the heavens and the earth—the Tower of Babel. But God was not impressed. God scattered the people and had them speak different languages. Diversity was the way forward.

Flash forward to Pentecost in the New Testament, which is described in Acts 2. It is interesting to see what happens when the Holy Spirit falls on believers in the young church as they are gathered together in one room. The writer goes to great lengths to emphasize how diverse the people were. They were Parthians, Medes, Elamites, Cretans, and Arabs; they were residents of Mesopotamia, Judea, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, Pamphylia, Egypt, Libya near Cyrene, and Rome (Acts 2:9–11).

When the Holy Spirit falls on them, the people begin to speak in “other tongues” (v. 4). We often think of this event as when they got filled with the Holy Ghost fire and things got rowdy. While that’s true, and they were in fact accused of having “too much wine” (v. 13), it’s also true that we sometimes overlook the real miracle in this event. As they heard the gospel proclaimed, each one “heard their own language being spoken” (v. 6). Despite their diversity, they were “one in heart and mind” and began to share possessions radically, holding all things in common (4:32).

As we look at the juxtaposition of the Babel story and Pentecost, something is strikingly clear. Unity is not uniformity. Oneness is not sameness. This is the key difference between what happened at Babel and what happened at Pentecost. Babel is about the power of a monoculture—people impressed with themselves and the possibilities of uniformity. Pentecost is about the power of God to bring people together across all that divides them. Unity exists most powerfully when there is diversity. And the more diverse we are, the stronger we are when we unite, and the more clearly we see God’s power at work to reconcile us.

Diversity is divine. Every human being is a reflection of God. And when we are surrounded by monoculture, by people who all look like us, we miss out not only on the full experience of God’s wonderful and miraculous creation but also on who God is. To have a consistent ethic of life is to be awed by life in all its diversity and complexity. That’s why I’m known to say from time to time, “If our community is all white, something’s not quite right.” And the same can be said of monoculture anywhere—it limits our vision, our perspective, our appreciation of the bigness of God’s love for all people. We are all a reflection of God, and we are all made from the same dirt.

Breathing Life into Dirt

Dirt is an interesting contrast to the color-full, wonder-full creatures God made. And perhaps that is part of the point. God makes beautiful things out of dirt. And God continues to bring new life out of the compost of Christendom. There’s a whole sermon there for sure, but we don’t have time for that one right now.

The word human comes from the Latin humus, which literally means “dirt.” It’s also where we get the word for the chickpea side dish called hummus, which, some people contend, does look and taste a little like dirt. The humus of humanity hearkens back to the fact that God took dirt and breathed life into it to make us. It is also why on Ash Wednesday we remember the dirt from which we were made and the dirt to which we shall return. God sculpted human life from the raw material of creation itself. God made beautiful things out of dirt and continues to do so today. Maybe you’ve heard that Gungor song “Beautiful Things,” which talks about how God makes beautiful things out of dust, and God makes beautiful things out of us. (I’m humming it now as I write.)

Adam, the name given to the first human being, comes from the Hebrew word adamah, which means “earth” or “the ground.” Adam was made from the earth. And the name Eve simply means “life.”[11] Isn’t that beautiful? Life was made from the dirt as God breathed into it. The fact that we are all made from the dirt means none of us should think too highly of ourselves. But the fact that we are also made in the image of God means that none of us should think too lowly of ourselves either.

There is a fascinating lesson from the rabbis of old that explores another aspect of God’s breath.[12] The rabbis suggest that the mysterious word for God in the Hebrew scriptures, YAHWEH, can actually be translated as “breath.” The Hebrew word doesn’t have vowels; vowels were added later to help the word make sense because YHWH is an odd word. But the rabbis suggest that this is part of the point. In the Hebrew alphabet, the vowels represent breathing sounds.

God is more glorious than we can wrap our heads around and doesn’t need a name. That’s why when Moses asks for God’s name, God says, “I am” or “I am who I am” (Ex. 3:14). God’s response can also be translated “I am becoming who I am becoming.” In similar fashion, YHWH has that reverent, mystical, transcendent quality that addressing God warrants. But here’s the cool part: the rabbis suggest that YHWH is the sound of breath. Even as you listen to your breathing you can easily think of inhaling “YAH” and exhaling “WEH.” On several occasions, I’ve been present when my friend Richard Rohr has led a group in a lovely prayer doing exactly that—breathing in YAH and breathing out WEH.

What if, just as God breathed life into the dirt, everything that has breath is praising God simply by existing, by breathing in and breathing out?[13] That is exactly what Scripture says: “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord” (Ps. 150:6). Jesus even said that if we don’t praise God, the breathless rocks will cry out (Luke 19:40).

My friend Jason Gray is a musician who wrote a beautiful song about the breath of God called “The Sound of Our Breathing.” When he introduces the song in a concert, he reflects on how wonderful it is to imagine that we are designed to say God’s name simply by breathing in and out, which means that none of us can go very long without calling upon the name of the Lord. When babies are born, are they taking their first breath or are they calling out the name of the Lord? Do we die when we breathe our last breath, or are we no longer alive because the name of God is no longer on our lips?

Here are a few of Jason’s lyrics.

Everybody draws their very first breath

With Your name upon their lips

Every one of us is born of dust

But come alive with heaven’s kiss. . . .

So breathe in

Breathe out

Breathe in

Breathe out. . . .

’Cause the name of God

Is the sound of our breathing

The deep conviction that life is good matters. Not only is life good, it is holy and wonder-full. It is a gift from God. Losing a sense of wonder and gratitude may be the first sign of a crack in a firm foundation for life. So protect your childlike wonder.

Creation is amazing. And the most sacred, beautiful thing God ever made is us. As incredible as all the creatures are, nothing is more sacred than human beings. Looking into the eyes of another person gives us one of our clearest glimpses of God. And the closest we can get to killing God is to kill or crush a child of God. Every single one of us bears the image of our creator. That’s what we’ll explore next.

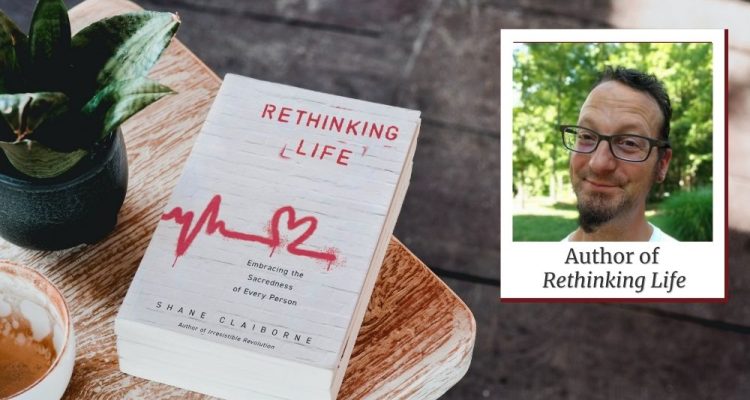

Excerpt from Shane Claiborne’s Rethinking Life, Zondervan Books, Published February 7, 2023, Used by permission.

Footnotes

[1] Paul Hawken, “Healing or Stealing? The Best Commencement Address Ever,” in A Sense of Wonder: The World’s Best Writers on the Sacred, the Profane, and the Ordinary, ed. Brian Doyle (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2016), 191.

[2] Dr. David Bradstreet and Steve Rabey, Star Struck: Seeing the Creator in the Wonders of Our Cosmos (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016), 19.

[3] Bradstreet and Rabey, Star Struck, 83.

[4] To be exact, it takes 8.3 minutes to get here, traveling 186,000 miles a second over 93 trillion miles. Which also means, if the sun stopped shining, it would take us 8.3 minutes to know that. The next closest star, Alpha Centauri, is so far away that it takes 4.3 years for its light to reach us over that 25-trillion-mile distance. Whoa. Bradstreet and Rabey, Star Struck, 249.

[5] I could go on and on about the wonders I learned from Dr. Bradstreet in Star Struck. For example, did you know there are nineteen essential factors that not only make life on earth unique and miraculous but also provide the precise conditions for life to be possible at all? I won’t go through all nineteen, but they are pretty spectacular. For example, the alignment of the earth’s poles is off by exactly 23.5 degrees, creating the earth’s tilt on its axis. That minor detail is why we have seasons and climates. Without the tilt, we would either burn up or freeze to death. The fact that the earth is 75 percent water is also clutch. Life on earth is possible because we have roughly 352,670,000,000,000,000,000 gallons of it, and because some of it evaporates and flows back to the earth as rain. The sun is just one of 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars. There are 200 billion stars in the Milky Way alone. But get this: in addition to ours, there are 200 billion more galaxies in the universe. The conditions for life on this little planet are truly a miracle. It makes you feel small and extremely special all at the same time. Bradstreet and Rabey, Star Struck, 58, 207.

[6] Bradstreet and Rabey, Star Struck, 43.

[7] Sometimes it’s not even intentional destruction but a subtler apathy about things such as climate change. For example, did you know that the temperature of sand determines the sex of sea turtles? That means that because the sand has become warmer from climate change, male turtles have become almost extinct. More than 90 percent of the newborn turtles on the Great Barrier Reef are now female, which means the survival of the species is in grave danger. “Over 90% of Turtles Born Female Due to Climate Change,” World Wild Fund for Nature, January 8, 2018, wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?320295/90%2Dpercent%2Dfemale%2Dturtles.

[8] I keep learning all the time. I just watched a documentary that said the three-toed sloth has eighty different species that live in its fur. Crazy!

[9] “How Many Languages Are There in the World?” Ethnologue, www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages.

[10] “Current World Population,” Worldometer, www.worldometers.info/world-population/.

[11] Don’t read too much into the fact that Adam, the man, is dirt, and Eve, the woman, is life. I think it’s enough to recognize that we are all equally fallen and equally holy. Maybe that’s part of the point. As reformer Martin Luther put it, we all have a sinner and a saint at war within us, and each day, each moment, we get to choose which we will be. Just as original sin is a part of the story, so is original innocence. Good stuff comes from dirt. New life comes even out of compost.

[12] To learn more about this, see Rabbi Arthur Waskow, “Why YAH/YHWH,” The Shalom Center, April 14, 2004, https://theshalomcenter.org/content/why-yahyhwh.

[13] This is all consistent with traditional rabbinical teaching, which is that life begins at our first breath, something I had a fascinating conversation about with Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg. I know it raises a potentially contentious issue about when life begins. We won’t get into that here, but we will explore it in chapter 12. Just giving you a heads-up. For now, the point is to simply ponder the connection between breath and life, and God’s breath giving us life.