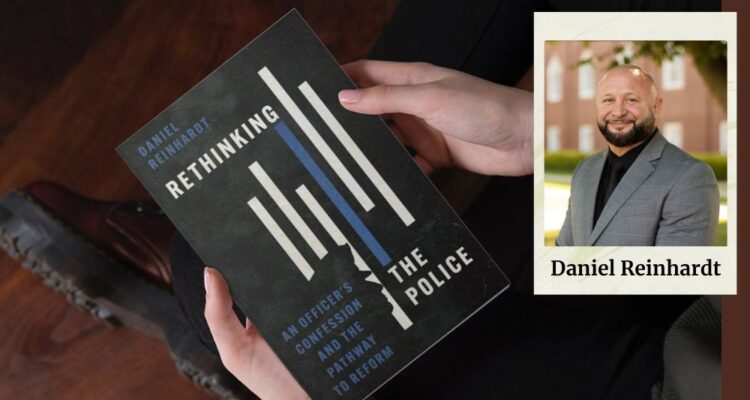

Adaptation from Rethinking the Police by Daniel Reinhardt

(Adapted from the Introduction)

I am a white male and was a police officer for twenty-four years in a racially diverse urban community. I was born and raised in the same community and lived most of my life in the city where I served. As a teenager, my high school had a dense population of African Americans. My wrestling team was coached by an African American man and most of the athletes were African Americans. Although only a few Caucasians earned spots on the team, I was fully welcomed and even loved. I developed friendships with my teammates, some of which have endured to the present day. After high school, I married an African American woman, and we have now been married for over twenty-eight years and have six children.

I am acquainted and even immersed to some extent in a diverse cultural context. I also have deep and meaningful relationships with African Americans. Yet sadly, neither my experiences nor my context freed me from the blindness and moral enslavement of police culture. For decades, I refused to accept what was painfully obvious for so many—police brutality against minorities is not an issue of a few isolated and disconnected incidents but a systemic condition of a compromised institution.

My Journey to the Light

I began my law enforcement career at twenty-two years of age. I spent four months in the police academy, learning laws and standards of conduct as well as training in defensive tactics, driving, and firearms. The academy also indoctrinated me into a particular culture. For the most part, police academies are managed by police officers, and the training is shaped by the stories and experiences that the instructors tell. As a cadet, you’re not just learning the curriculum, you’re absorbing the officers’ attitudes, vocabulary, and mannerisms, and the instructors are seasoned cops, which is the future every cadet hopes to achieve. I remember one instructor whose extensive experience in street crimes captivated me. As a young man, I admired him and hoped to be just like him. Looking back, I can see how my experience in the academy began to reshape my thinking, speech, and even who I perceived myself to be.

After the academy, I spent four months with training officers. Approximately eight months after I first walked in the door of the police department, I was on my own in a police cruiser. My grasp of the power I possessed did not run much deeper than a single, superficial thought: I cannot believe they are letting me do this. Within my first year of experience, I found myself involved in car chases and fights with suspects who resisted arrest. I was on the scene at bar brawls and arrived in the aftermath of rapes and murders. On one occasion, I witnessed an officer shot and later stood less than fifty feet away as two other officers killed the suspect. This was my new normal, yet I still had not meaningfully reflected on the implications. But then something happened during one of my night shifts that forced me to reckon with the power I possessed.

Domestic violence calls are common at night, but this one would turn out to be anything but. The female victim was screaming so loudly that the dispatchers could hear her as the neighbor across the street reported the incident from their front lawn. I was only a block away when I received the call, but my backup officer was blocked by a train. When I arrived at the residence, I could hear the visceral screaming, and I was alone.

I walked up the broken steps that led to the front door, which was open but obstructed by a screen. I pulled it open and stepped inside the residence. Ten feet away, I saw a couch facing the door where a woman crouched as an African American male loomed over her. They were involved in a struggle, and she was screaming. The motion of the man’s arms and the intensity of the woman’s screams made it clear to me that she was being stabbed. I unholstered my gun and pointed it at the man, yelling for him to stop and to get on the ground. Instead, he turned toward me. In less than a second, he had closed the space between the couch and the doorway, leaving me no time to retreat.

My academy training had taught me that deadly force was the appropriate response to a knife attack. I knew that I could not stop him with my left hand alone, but I had no time to holster my weapon to free my right for self-defense. So I took the slack out of the trigger, preparing to fire.

But I never pulled the trigger.

For reasons that I could not explain at the time, I chose instead to grab the young man’s right hand with my left hand, knowing full well it wouldn’t be enough to stop the knife. To my surprise, he didn’t resist. I turned him toward the wall and handcuffed him. Still, there was no resistance. Finally, I turned him around to secure his knife.

It wasn’t there.

Despite my certainty seconds earlier, there was no knife, and there never had been.

Once I realized he was weaponless, I asked him, “Why didn’t you listen to me? Why didn’t you get on the ground?”

With anger and utter sincerity, he yelled, “I’m tired of her! I came out so you could take me to jail.”

I walked the man down the front steps I had crossed only a few moments earlier and placed him in the rear of my police cruiser. When I sat down in the driver’s seat, my hands began to tremble, but not because of stress or concern that my life had been in danger. I was used to those feelings by that point. Instead, I trembled at the realization that I nearly killed a man who had no intention to harm me.

For many years, I couldn’t explain why I never pulled the trigger and ended that young man’s life. My choice was completely inconsistent with my training. I was fully convinced that he was about to stab me and knew I couldn’t stop him by grabbing his hand. More than twenty years later, I now see that my faith was a key part of my response. Because I believed that young man was intrinsically valuable and created in God’s image, I valued his life. My values countered my training, tipping the scales in that encounter, and I am forever thankful they did.

Here’s what I’ve learned from that call and other experiences over two decades of law enforcement:

Police culture matters. Police officers are shaped by police culture, and that internal culture is present in every experience and every encounter they have as officers.

Internal culture shapes the ways police officers use force. If the culture does not promote valuing people and relationships within the community, the exercise of power—and specifically the use of force—can have catastrophic consequences.

Change is not impossible. Influences both within officers and in the culture of their department can reshape police officers and reorient the choices that they make.

The police will continue to use force, and officers will be in in situations like the one I described where their choice is literally a matter of life and death. Unfortunately, this is a consequence of living in a fallen world. We cannot change that reality; however, we can take meaningful steps to ensure officers are shaped in a way that truly promotes valuing the lives of people—particularly people of color.

Adapted from Rethinking the Police by Daniel Reinhardt. © 2023 by Daniel Reinhardt. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press. www.ivpress.com.