On September 12, 2001, I had an encounter with police that could have ended far worse than it did. The tension was high that day. Terrorists had attacked our country twenty-four hours earlier. I was a junior manager for a large retail company, and I had just finished up the evening by closing the store. With the night crew inside stocking shelves, I followed protocol by driving my car around the building to be sure that it was secure.

When I reached the side alley of the building, I noticed a car backed in beside an emergency exit door. The car had no license plate. The terrorist attacks weighing heavily on my mind, I was afraid someone may have been hiding in the store. In order to make sure that my night crew was safe, I called the police.

Three to four minutes after calling 911, three or four police cars abruptly surrounded my car. I had no clue what was going on. The drivers were shining their high beams into my car, and the light completely blinded me. I did not know who was there, how many of them were surrounding me, or whether they had guns drawn on me. I froze. Then I cried. I didn’t want to die.

Eventually, they yelled through a megaphone to roll my window down and place my hands outside the vehicle. My car didn’t have automatic windows, so rolling the window down meant dropping my hands below their line of sight. I couldn’t see them, what they were doing, or how close they were to me. I assumed they had their guns drawn, so I stayed frozen. Then I cried more. I didn’t dare move a muscle. My fear for my own life told me that as soon as I reached down, they would kill me. So here I was in an alley on the side of a store preparing to meet my Maker because I was certain I was about to be shot.

After what seemed like an eternity, one lone officer approached my car. He must have told his fellow officers to turn off their lights, then he tapped on my window and told me that I was going to be okay, and he kindly asked me again to roll down the window. I was terrified, and he knew it, and he saved me and the other officers from reacting in a way that could have ended my life. I was thankful that he didn’t let fear control him or the situation. He did not know me. He did not know that I was the person who made the initial call.

As I reflect on the encounter, two factors played a significant role in the way I reacted: I am Black, and I am autistic. What I wish I had known back then is that many people who are neurodivergent process information differently than those who are neurotypical. Neurodivergence usually includes autism, ADHD, and other neurological differences. One way that neurodivergent brains operate differently has to do with executive functioning, or how the brain absorbs information, organizes it, and acts on the information in a manner that is safe and effective. In intense and high-stress situations, executive functioning can become challenging, if not impossible.

I don’t tell this story very often because for so many people these are not unusual occurrences. They happen regularly. I am grateful that those officers spared my life when all the ingredients for a fatal shooting of an unarmed, young Black male were present. I have lived to talk about it, but so many others have not.

In August 2019, police in Aurora, Colorado, approached twenty-three-year-old Elijah McClain after they had received a 911 call reporting a “suspicious person” walking down the road in a ski mask and behaving strangely. When officers confronted McClain, he repeatedly asked the officers to let go of him and announced that he was going home. Elijah was a young, Black, autistic man.

Those who have sensory-processing challenges, which are common in autistic individuals, are often averse to touch, especially when they do not initiate contact. The body camera transcripts of the event record McClain repeatedly asking the officers to let him go, pleading with them, “Please respect the boundaries that I am speaking.” We can also hear McClain explaining his plan to go home. Another common characteristic of autism is difficulty switching from one activity to the next without a thorough transition or additional time to adjust to the new expectations. The random police officers approaching McClain for an unknown and undisclosed reason most likely interfered with his internalized plan of simply going home.

Finally, we hear Elijah stating, “I’m just different, that’s all. I’m just different.” Many believe this was Elijah’s way of trying to explain his autistic behavior and neurology to officers who deemed his behavior strange and, eventually, dangerous.

Officers at the scene eventually restrained McClain, who weighed only 143 pounds, using a choke hold. When paramedics arrived, an injection of ketamine was administered to calm him down. Because of the strength with which he resisted the officers, they wrongly suspected McClain was on drugs at the time of their encounter. Ketamine is a powerful sedative, and the paramedics administered Elijah a dose that was nearly twice the amount recommended for an individual his size. Shortly thereafter, Elijah stopped breathing. They then took him to the hospital, where he would die three days later.

Elijah McClain had no weapon. His family later reported that Elijah suffered from anemia, which made him cold, so it was not uncommon for him to wear a ski mask in order to keep warm. The investigation found that the Aurora police had no legal basis to stop, frisk, or restrain Elijah. Essentially, Elijah died because of implicit racial and ableist biases.

Implicit racial bias strongly shapes the treatment of people of color in the US judicial system. According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, the NYPD, from 2002 to 2011, conducted stop and frisk procedures on millions of citizens, about 90 percent of those being Black and Hispanic people. Eighty-eight percent of those minorities who the police profiled and stopped had no weapons or contraband. Often, what leads to such practices is the perception that Black and Brown bodies and the behaviors they display are inherently more aggressive—and therefore more dangerous.

There are several research studies that have found that compared to White people, Black people are far more often subject to automatic and subconscious negative stereotypes and prejudice. These thoughts usually extend beyond just negative attitudes; Black and Brown bodies are associated with violence, threatening behavior, and crime. Black men are also more likely to be misremembered for carrying a weapon because of this bias.

Let’s be honest: The stories I am sharing with you are not unusual. There’s nothing new about the statistics that prove racial bias is a reality in our country. There’s nothing new about Black authors, scholars, activists, and clergy speaking up about these issues. What is new, and what I am aiming to bring to this ongoing discussion, is that racial bias in America is not simply an issue of race. It is not simply an issue of skin preference. It is not just an issue of a lack of diversity. Race-based slavery and the enduring racial bias and discrimination it created are about disability discrimination as well. Our issues with racism are in fact issues of ableism— and American Christianity has played a significant role in influencing ableism in our present cultural context.

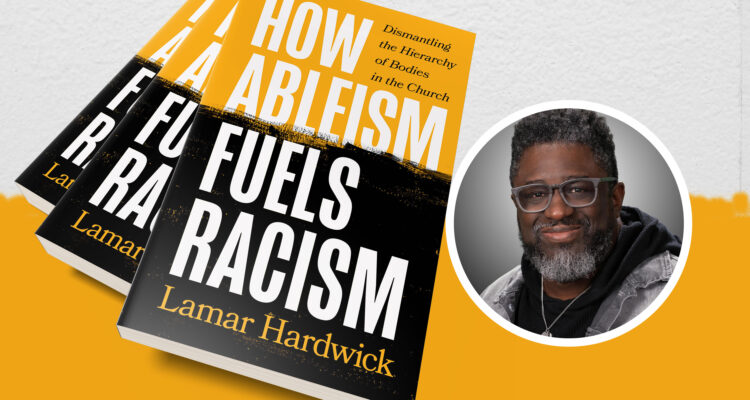

Content taken from How Ableism Fuels Racism by Lamar Hardwick, ©2024. Used by permission of Brazos Press.