Adapted from Chapter 4, “Isolated and Othered”

“Pick a color,” she said. “Write down your color.” I was at a writers’ workshop in Minnesota, and this was our prompt. I wrote down “pink.” No one else will pick that color, I thought to myself. Then we were told our assignment: head outdoors and look for the color we had chosen.

I couldn’t find anything pink. It was cloudy, with no streaks of a pinkish sunset brushing the sky. I spotted peach-colored raspberries ripening on the vine. Spiky lavender thistle blooms swayed high above the grasses. I detected tiny maroon slivers of crushed stones in the concrete road. Otherwise, I was surrounded by swaths of green grass and leafing trees in shades of emerald, jade, lime, pistachio, sage, and artichoke. No pink anywhere.

Should I change my color? No one would know.

No, I’ll be honest and stick with pink.

Then I remembered a science lesson. The color we see with the naked eye is the hue that is not absorbed by the object; what we see is the color reflected back to us. Green leaves and grasses absorb every color in the spectrum except green, so what I see bouncing back to my eyes is green. That meant pink really was everywhere, even if my human eyes could not see it.

Similarly, when I see your face, I see dimly. I can’t see your past, but if I’m paying attention, I might detect bits of joy flashing when your eyes light up. I can’t see your thoughts—though sometimes your emotions give themselves away. Sometimes, we only reflect back to others what we want them to see. Sometimes we think what we can see with our human eyes is all there is. Sometimes all others see is “different,” when there are really rich tones of melanin and shades of brown reflecting back, with all of their accompanying tones, tints, stories, and songs.

Colorblindness

In an attempt not to sound racist and separate themselves from obviously racist individuals, some folks will say, “I’m colorblind.” But the truth is we are not colorblind. Babies and children actually notice race at young ages—some studies indicate as early as three months. By nine months, babies use race to categorize faces, and by age three, children associate some races with negative traits.

I’ve heard the idea that America is colorblind: America elected a Black president, and therefore, we’ve overcome our obstacles. Electing a Black president is something many did not believe would occur in their lifetime, so does that now mean we’ve achieved racial equity? Electing a Black president did not change the fact that Black Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of white Americans. Electing a Black president did not radically alter the tragic number of police brutality cases against Black people. Likewise, just because we have neighbors in a racially mixed marriage, or a couple at our church adopted Black or Brown children, or we did so ourselves, does not mean that we’ve achieved ethnic and racial harmony. Proximity does not erase structural inequality.

We can see color, and the idea of colorblindness actually cloaks the real issues of living in a racialized society and the systems perpetuating it. Colorblindness doesn’t work toward injustice. It may be well-intentioned, but colorblindness actually causes harm. “Colorblindness has a kind of homogenizing effect on communities: it suggests unity through uniformity instead of belonging in spite of difference,” according to David P. Leong, author of Race and Place. Instead, we are “color-blessed,” as Dr. Derwin Gray, pastor, author, and former NFL player, says.

***

In the science lesson I discussed where the only color visible is the one not absorbed by an object, we learn that the physics behind color itself is a multidimensional story. If color is a wavelength of light, then white is actually not a color on the visible light spectrum. When we see white, we are seeing all the colors bouncing off the object and hitting our eyes.

For objects that appear black to our eyes, we are seeing the color black because all the colors are absorbed by the object; nothing is reflected back for us to see. That’s why darkness looks black: there is nothing for us to look at.

It is curious that humans chose these two “non-colors” to describe color in each other. The physics behind the colors themselves is representative of what has taken place in our world, and how people of color from the African continent became referred to as “Black,” as if they were seen as nonexistent, nonentities. Colonizers and slave handlers erased their humanity by treating them as slaves and subjugating them. That is how many have chosen to “see” Black folks: not worthy, less-than, dehumanized. Additionally, the racial divide is often defined by this Black-white binary, yet there is so much more to be known, so many colors in-between.

***

El Roi

Imagine having a name that meant “Foreign Thing.” Unthinkable, right? Yet, that is the approximate translation of Hagar, the name of Sarah’s handmaiden. Sarah was married to Abraham, but in the story, Sarah gave Hagar to Abraham because Sarah and Abraham had no children. Hagar then gave birth to Ishmael. But Hagar’s name, which isn’t really a name, means something like “foreign thing.” And this is exactly how she was treated. Not as a person with autonomy, but as a slave, an object to be used at will. When Hagar was forced out of Abraham’s household, God met her in the desert, told her to return to the household, and declared that her son should be named Ishmael, which means “God hears” (Gen 16:11). Hagar responds by naming God El Roi, which means “the God Who Sees.” The “Foreign Thing” was seen, heard, and known.

Though we may walk through life unknown by society at-large or in majority white spaces, we are known by the Creator. Being known necessitates a curiosity beyond stereotypes and toward specifics. Being known means we are known completely and loved by a Creator who sees the good, the bad, and the ugly and loves us anyway.

Indeed, we have a God who sees us and knows us. We are not foreign things but beloved people, those who belong. We are seen, heard, known, loved, and embraced. And if culture at-large doesn’t see us or know us for who we are, we can be certain that God does and will not stay silent forever. We are not isolated or forgotten; we are seen, and as we negotiate belonging and assimilation, we are integrated into the story of humanity, and a story of love and belonging crafted by a God who sees.

So, What Are You?

God knows your name

Your past, present, future

You are seen, remembered, known

In the land you are looking for

You belong both/and

There is no either/or

You are known

And loved as-is

You are not out here

Making it all alone

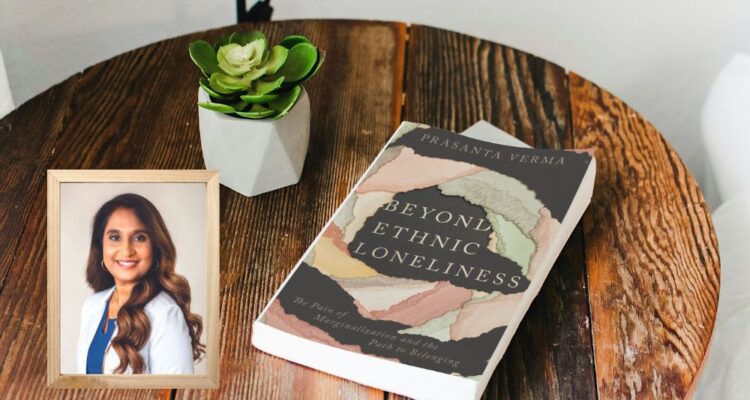

Adapted from Beyond Ethnic Loneliness by Prasanta Verma. ©2024 by Prasanta Verma Anumolu. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press. www.ivpress.com.