“One failed attempt at a shoe bomb, and we all take off our shoes in the airport. Thirty-one shootings since Columbine, and no change in the regulation of guns, ” the comedian, John Oliver quipped, reminding us how the jester can startle us with our tragedies.

The numbers are wrong, of course. The shootings on our nation’s campuses keep escalating. In the last months, our stomachs lurched when we read the headlines. Two middle school students were injured in New Mexico. A student at Widener University was shot. A teaching assistant was killed at Purdue University. A student was killed with a gun at South Carolina State University. This week, a music major was killed by her fiancé, at a Christian school. He was majoring in Christian ministries.

The events continue a worrisome trend. In 2013, someone fired or threatened to fire a gun 28 times on our campuses. In the United States, children are twelve times more likely to die from a firearm injury than in twenty-five other industrial nations combined. Since 1963 more than 166, 000 children and youth died from guns in our country, a number that exceeds the number of U.S. Soldiers who died from wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq by three fold.

In light of all the shootings, it seems like we ought to be able to pass gun restrictions. Isn’t it obvious that we are causing harm to ourselves? How can we, at least, learn how to reduce harm? Why are efforts to stem the violence so fleeting? Instead, it seems like we’re entertained by violence.

Related: If Jesus is a Pansy, I want to be one too — Reflections on Christlikeness

Tyler Wigg-Stevenson, wrestles with our attraction to violence in Fighting for Peace: Your Role in a Culture too Comfortable with Violence (Zondervan 2014). As he looks at violence, particularly when it comes to our entertainment, he writes, “Violence is a weird thing to enjoy. Violence is different, after all, than our other extreme impulses. Fat and sugar taste delicious; that’s why we eat too much of them. Sex feels fantastic, primally so, that’s why we crave it. But violence? Violence hurts. So why on earth do we want it so badly?”

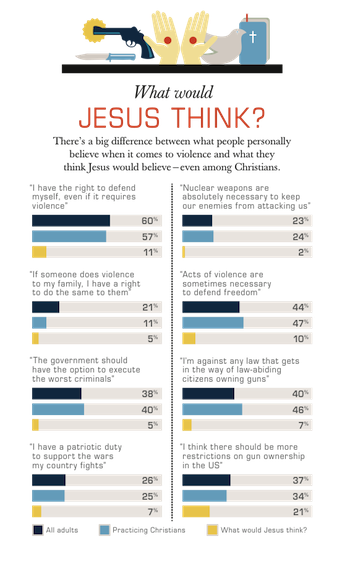

The question becomes even more perplexing for practicing Christians. We are called to follow the Prince of Peace, a man who preached “blessed are the peacemakers.” And yet, there is a stunning difference between what practicing Christians would do in particular situations and what we believe that Jesus would do.

Why is there such a difference? Wigg-Stevenson explains that our nation is addicted. In much the same way that we crave other destructive behaviors, we are a culture with a lust for violence. What can we do in response? How can we begin to reduce the harm we cause ourselves?

A psychologist told me about a young patient he had. The girl was a cutter. After living through a childhood of horrible abuse, she had become emotionally numb. The dulling was a mechanism that allowed her to survive, but now that she was a teenager, she wanted to be able to feel things. She cut her wrists, not in an attempt to kill herself, but because she wanted to remind herself that she was alive.

The psychologist had been skilled at turning around this particular behavior and I asked him how he did it.

“I don’t tell them to stop, ” He answered. “Instead, invite them to experiment with different tools. After a while, I can usually talk them into going from a razor, to an eraser, to a red pen.”

I was horrified. “Isn’t that scary? Aren’t you condoning risky behavior?”

He angled his head thoughtfully, “Yes. But it works when nothing else does.” When the interventions, hospitalizations, and medications had no effect, meeting the girl where she was did cure her.

He angled his head thoughtfully, “Yes. But it works when nothing else does.” When the interventions, hospitalizations, and medications had no effect, meeting the girl where she was did cure her.

The psychologist engaged in a harm reduction model of therapy. Social workers and counselors often use this model to meet people where they are, then lead them through steps to reduce risks.

It’s very controversial, especially when it comes to things that seem so black-and-white for Christians. Advocates of harm reduction may not be able to persuade a sex worker to leave her trade, but they might be able to get her to use a condom or get tested for AIDS. A social worker may not be able to get someone to stop abusing drugs, but she might be able to get him to use clean needles.

Also by Carol: Sex, Pills and the Image of God

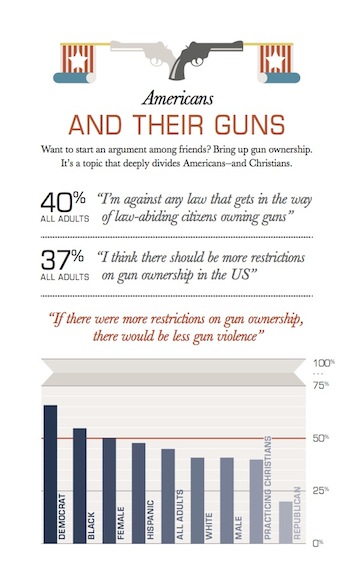

So, if we as a nation have an addiction to violence and we cannot stop handguns on our streets, can we at least do something to reduce the harm?

This is what Christians have been doing in the D.C. area. When D.C. churches found out that nearly one in three guns confiscated in the District and Prince George’s County came from one place, the faith community began to organize a prayer vigil at Realco guns. The store had been selling without background checks, and their customers were people with criminal records and mental health issues. The Christians gathered, prayed, and commemorated the victims and families that had been touched by shootings. Vigils, protests and prayers became a weekly practice, a discipline for those concerned about violence, a way to reduce harm.

The gun lobby is strong in our country. We may not be able to stop the guns that have been flooding into our streets. Some Christians may not even want to. But in light of what we are doing with our addiction to violence, can we at least look at ways to reduce harm? Can we get behind common-sense restrictions? Can we begin to understand that this is a spiritual problem and try to align what we would do with what we believe that Jesus would do?

Source for graphics: Fighting for Peace: Your Role in a Culture Too Comfortable with Violence (HarperOne)