All of us in the United States arrived here as immigrants, refugees, or slaves. The only exception is Native Americans. This land was originally their land. For the immigrant, the U.S. was a land of hope. For the refugee, it was a place of asylum. The slave was unwillingly brought here. But we have all, together, made the United States our home.

My family, who were Irish, sought America as a place where they could make a new life. The exact details of what precisely brought them here are lost in the sands of time, only known through their folklore. But at the core of it, we know why they came — the American Dream.

Is the American dream any longer truly American, if it is not the hope for all people who seek a new life or refuge in this land? Even for those whose ancestors came here against their own will, the American dream became something worth fighting and dying for. Many African Americans fought in the Civil War with the hope of becoming free. And many sought refuge in the North to join the great fight for abolition — believing that Abraham Lincoln would honor his word.

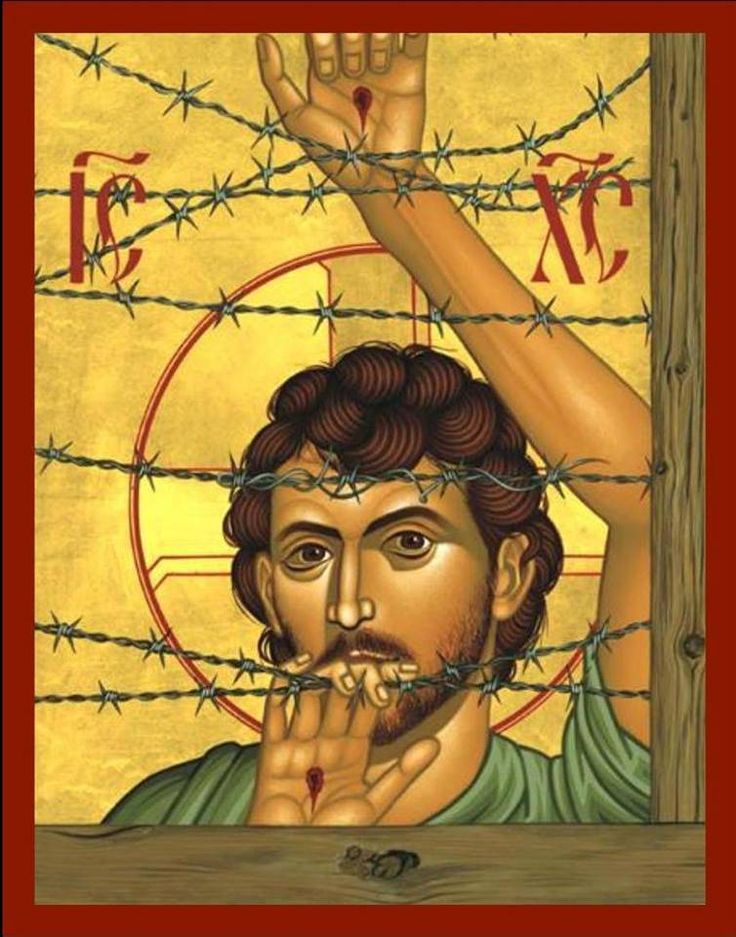

There are all kinds of arguments about the history of America that can be made in favor of refugees and immigrants having a place here. But today I address Christians. And for you, my dear Christian brothers and sisters, I implore you to hear the words of the book you so rightfully claim as the bedrock of the great nation of America. I am not arguing today about policy or politics. Today, I am arguing about human dignity, based on the scriptures we hold so dear.

Yahweh, our God, said to Israel — the same nation so many are quick to protect:

“You will not mistreat an alien, and you will not oppress him, because you were aliens in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 22:21 LEB).

“And when an alien dwells with you in your land, you shall not oppress him. The alien who is dwelling with you shall be like a native among you, and you shall love him like yourself, because you were aliens in the land of Egypt; I am Yahweh your God” (Leviticus 19:33–34 LEB).

From the beginning of Israel as a nation, there is recognition of the pain of oppression. There are laws made to protect the asylum seeker (the sojourner) and the immigrant. Justice demands justice for all — not just for a select few. We cannot say, “We shall love this person this way, and that person another way.” Furthermore, the very reason why Americans have the right to cast a vote is because we were once allowed into this country, or we were incorporated into it.

The reality of what God demanded of Israel comes into full picture when we read the next lines of the same passage in Leviticus, which lays out laws about the refugee:

“You shall not commit injustice in regulation, in measurement, in weight, or volume. You must have honest balances, honest weights … I am Yahweh your God who brought you out from the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 19:35–36 LEB; compare Deuteronomy 25:13–16).

The proximity of this verse to the one about the refugee or immigrant cannot be ignored; the implication is that the refugee or immigrant is the very person who was most likely to be treated unjustly. Thus, God makes provision against this.

Let’s fast forward in time to the New Testament, to see how this same language is reflected. In 1 Peter 2:11, the language of sojourners and exiles is used to describe Christians. Peter uses refugees as a metaphor for all Christians. We are living in a world that no longer reflects God’s full justice and ideals. If we are to call ourselves Christian, we must recognize that there is no difference between us and the asylum seeker or immigrant.

The plight of humanity — the difficulties in our world — is shared between all people. This is the case no matter what our background is, income level, or race. We are equal before the eyes of God (Galatians 3:28; Colossians 3:11). We are all in desperate need of God’s justice in our world. It is the best thing for all of us.

I’m not making a case here that I have the answer to the precise policy that America should use. In fact, I’m not even arguing here about policy or politics. Instead, I’m making the argument that the biblical view of immigrants and refugees is simple — they’re like us, and we’re like them. Furthermore, the Bible is clear that we are to do something in favor of justice, always — and that we are to find a way for the person seeking asylum to have it. And finally, there must be room for the immigrant in the world to have the same rights as everyone else.

No matter how we welcome the refugee and immigrant — no matter how we choose precisely to be hospitable and loving — we must acknowledge that the Christian response is love.