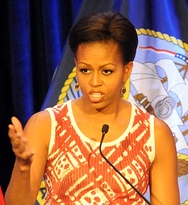

Last month on her official trip to Africa, Michelle Obama gave a speech of encouragement to 76 young sub-Saharan African women participating in the U.S.-sponsored Young African Women Leaders Forum in South Africa. The young leaders are all actively working towards social and economic improvements in their respective countries and communities.

Last month on her official trip to Africa, Michelle Obama gave a speech of encouragement to 76 young sub-Saharan African women participating in the U.S.-sponsored Young African Women Leaders Forum in South Africa. The young leaders are all actively working towards social and economic improvements in their respective countries and communities.

They gathered at the historically significant Regina Mundi Church in the black township of Soweto where 35 years ago in 1976, South African youth courageously and nonviolently protested Apartheid laws affecting their education. Many of those students lost their lives in the ensuing government issued police open shooting.

Today this church is a memorial of those who refused to sit idly by as their country and people continued to suffer under the horrors and injustices of Apartheid. It was here that Michelle Obama had the opportunity to share words with 76 young women. Washington Post reporter Krissah Thompson, who traveled with the first lady, writes that she challenged them to be the generation that ensures women are no longer “second-class citizens, ” fights the “stigma” of HIV/AIDS and “stands up and says violence against women” is a “human-rights violation.” It has been refreshing to have young African women in the international spotlight in a way that’s oft ignored, highlighted not as refugees of war, victims of violent rape and female genital mutilation, contagions of HIV/AIDS, or recipients of monthly dollar pledges. For one day a couple of weeks ago, the world was offered an equally significant glimpse of the African female population, dedicated, persevering, brilliant women committed to using their gifts and talents to highlight awareness, nurture justice, and improve the conditions of their respective African countries.

As a person of faith I often think about the power that our cultural imaginations have to draw us either closer or further away from a God-centered imagination. No one can deny that the way we visualize, imagine and depict people in any culture has repercussions for how we engage one another. It affects how we practice loving “our neighbor as ourselves, ” and honoring the dignity of one another as equal children of God each with unique God-given capacities to offer life-giving practice and witness this side of the kingdom. The fact that in the West, we are mostly exposed to stories or images of African women as victims in desperate political, health or socio-economic situations, influences how we imagine we are called to be in relationship with our sisters spread throughout the 53 countries in Africa. While it is important for the West to acknowledge the legitimate real needs of Africans caught in political and unjust socio-economic strife, an unbalanced portrayal of African women (and men) as poor and helpless risks the danger of fostering an “us/them” mentality that underwrites a pervasive Western notion that as Christians we are called to go and help the “helpless non-Western other” (quotes mine.) For many in the West this plays out in a gentile condescending relationship that entails reaching out to “those less fortunate than ourselves, ” and encourages us to imagine African women mostly as potential benefactors of Western compassion and generosity.

One White House aide claimed that the 76 women participating in the Forum were “some of the most awesome women in Africa.” Recognizably this was a compliment but the fact is that such African women are an anomaly only within Western imagination. In reality there exist countless ordinary, daily stories and images of women across the African continent that witness to a fuller picture of what it means to be an African woman. Stories that if told in equal parallel with the stories of need and suffering might lead to a broader depiction and more faithful imagination in the West of seeing African women, and actually women in other non-western countries in general, as having as much to offer their respective countries and those in the West as we suspect we have to offer them. We might learn to imagine ourselves, all of us together, as co-laborers striving to manifest the kingdom of God right where we are placed, and sometimes crossing boundaries to work alongside one another, empowering one another. I think of African women like Marguerite Barankistse, a Burundian christian whose story still amazes no matter how often one hears of it. Women like Dr. Kaswera Kassali, who with her husband Dr. David Kassali returned to their native war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo to create Congo Initiative because they “felt called by the Lord to help rebuild lives, families and communities through holistic ministries with churches from various denominations.” Women like Ghanaian theologian Mercy Amba Oduyoye, who directs the Institute of African Women in Religion and Culture at Trinity Theological Seminary in Ghana and writes about Christian theology from a feminist and African perspective. Women like Nigerian, Harvard business school graduate Ndidi Nwuneli, who returned to West Africa to start nonprofit organizations that promote and teach leadership to young women. I also think of young women like Delicia Beatrice Kotugondo, one of the Forum participants from Namibia who works with the National Youth Council of Namibia to support leadership and business development in Southern Namibia.

Having been raised in a couple of different African countries and visited several others I know that there are so many unnamed African women across diverse socio-economic boundaries whose daily, ordinary lives tell beautiful and inspiring stories of strength, communal care and reliance, and healing that ripples across generations. Collectively, the witness of all these women, those in the spotlight and those unnamed helps stretch our cultural and holy imagination of what we might be called to, what we might be capable of, and with whom we might be invited to join alongside, where the work of God is already in motion.

—-

Enuma Okoro (M.Div) was born in the NYC but reared in four countries on three continents. A writer, speaker, consultant, and retreat / workshop leader, she writes regularly for abc Good Morning America, Sojourners, Christianity Today and others. Okoro is the former director of the Center for Theological Writing at Duke University Divinity School, of which she is a graduate.

Her spiritual memoir, Reluctant Pilgrim: A Moody, Somewhat Self-Indulgent, Introvert’s Search for Spiritual Community was released in September 2010. She is also co-author with Shane Claiborne and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, on Common Prayer: A Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals. When she’s not writing she can be found with a cup of coffee or a glass of wine in hand, depending on the time of day. Visit Enuma at www.enumaokoro.com

A version of this article was originally posted on Christianity Today’s Her.menuetics blog