We never skipped a Sunday. Unless one of us was too sick to go to church, my parents faithfully ensured that every member of our family worshipped together every Sunday morning.

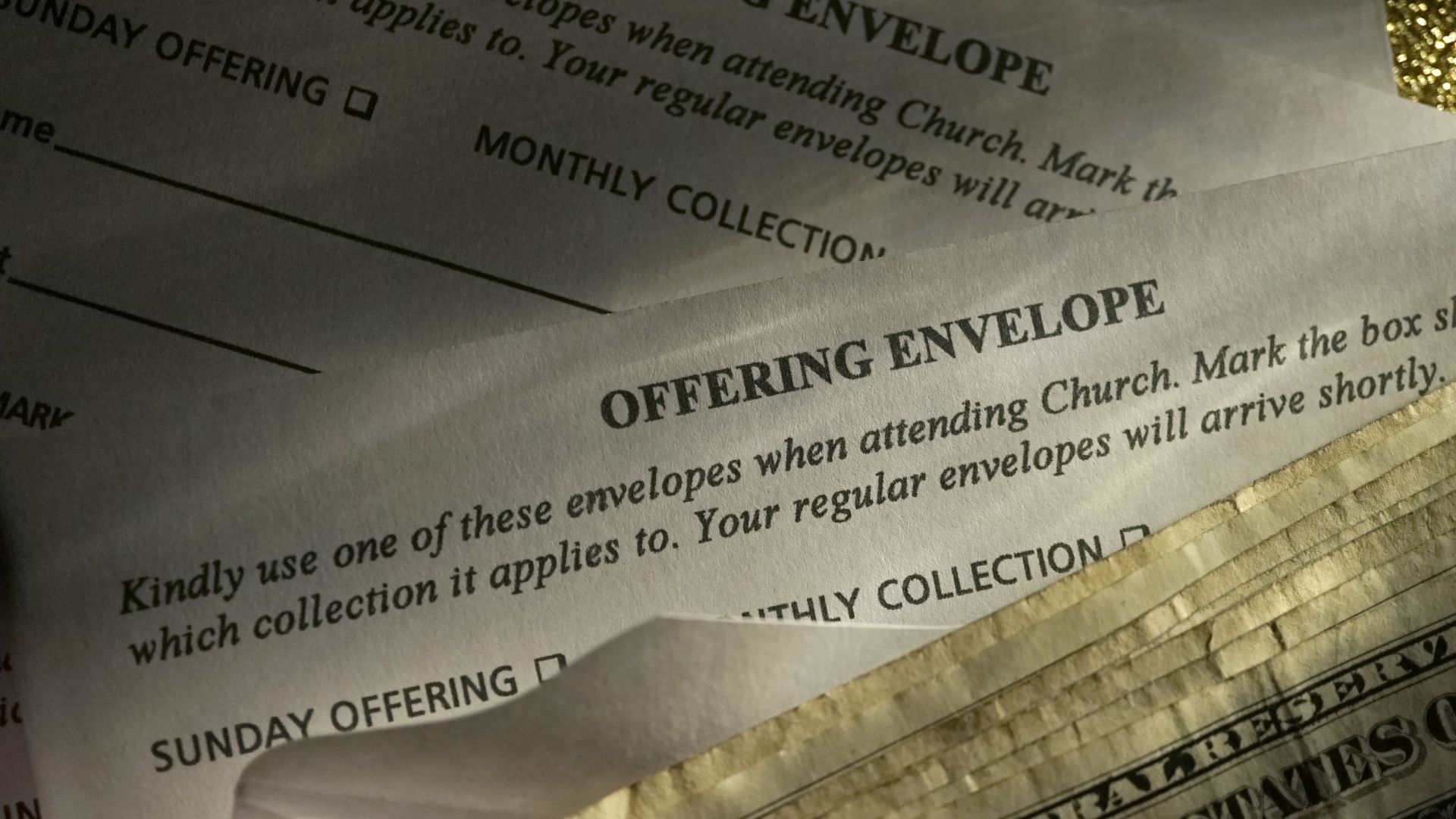

And every Sunday morning, I watched as my parents faithfully dropped their offering, safely ensconced in an envelope, into the offering plate.

As we got older, I paid close attention to the care that my mom put into this weekly offering. It was always their first fruits. My parents faithfully served in all of our churches in a variety of capacities. My father worked as a teacher or administrator in the attached schools and led Sunday morning Bible studies. My mother played the organ, accompanied the choir, and served on altar guild. In all of the ways my parents served the churches where we attended throughout my childhood, it never impacted whether or not they gave an offering every week. Like most church-worker families, we grew up lower middle-class. Yet, they still faithfully gave, confident that their financial gift would be used to further God’s heavenly Kingdom.

And like most church-worker kids (I didn’t become a PK until I was in my 30s and my father finally fulfilled his dream of becoming an ordained minister), I grew up well aware of the struggles of congregations to make it through to the end of the fiscal year with balanced budget sheets and finances in the black.

Contrary to the messages sent by megachurch pastors, most congregations (big and small) struggle to make it through the year with all bills paid. Those who go into church-based careers do not go into the ministry with the intent of making a lot of money. It is not a quick path to wealth, and more often than not, it has the opposite effect on workers and their families.

But for those on the outside looking in, it is getting increasingly difficult to see the American Church as anything but a place where business interests trump the interests of spreading the Gospel.

As scandal after scandal has erupted over the last couple of years, the common refrain exposes “ministries” that prioritize staying open ahead of the interests of the very people who are being hurt by the ministry. When David and Nancy French released their report on the abuses at Kanakuk, one of America’s largest Christian camps, they uncovered years of sexual abuse that had been covered up by NDAs and threats levied against the families of victims. The camp prioritized continued “ministry” over the mental health and spiritual well-being of any and all potential victims of abuse. Jacob Denhollander, husband of Rachael Denhollander, the lawyer and activist whose testimony jump-started the case against Larry Nassar, has openly discussed the financial liability of her work on church-related sexual abuse issues. They are fighting churches that are using the money entrusted to them by church members to cover up the abuses inside their walls so they can continue the ministries that are supposedly helping people.

How messed up is this?

READ: How the Year of Jubilee Challenges Us to Confront Monopoly Power

My childhood was spent in the church. Most of my adult career has been spent in ministries connected to churches. I believe in the good that the Church can do. As a Christian teacher, I’ve seen the incredible good that can be done inside Christian learning institutions. But we need to take a good long look at what we are becoming.

I’ve been often told that excellent programs are a means to an end: a way to get people into the doors so that they can be ministered to. I’ve seen what happens when ministries struggle financially or do not have the means to do good and effective work. A ministry on the brink of closure isn’t doing much good to anyone. The uncomfortable truth is that money makes the world go ‘round. Ministry cannot happen without financial support from the very people who are participating in that ministry. But how should we handle Christian organizations when the survival of the institution comes at the expense of the very people the organization is supposed to serve?

In a recent New York Times piece by Kristin Kobes Du Mez, she wrote, “My own research into the history of evangelicalism made clear to me the perils of covering up harsh truths in the interest of protecting the brand — or, in the words of evangelicals themselves, ‘the witness of the church.’” While she was talking about the uncomfortable history of evangelicalism in relation to the bigger picture of American history, this statement rings true for all facets of American Christianity where protecting the brand—the business of ministry—is more important than the actual mission of Christ.

And it’s damaging the growth of the Kingdom.

When I look at my friends who have been marginalized in the membership rolls, deemed by mainstream Christians to not belong in full church membership, they don’t hear the invitation “come as you are”; they hear “come as we want you to be.” Churches need to keep the clientele that keeps their church doors open and cannot risk alienating them. They can’t afford to “risk” waiting on the broken to begin financially supporting their ministries. In theory, these churches genuinely believe that they are doing God’s work inside the buildings and in communities, but at what expense?

Jesus overturned the tables of the money-changers and merchants in the temple, reminding his disciples, “My house will be called a house of prayer, but you are making it a ‘den of robbers’” (Matthew 21:13 NIV). Instead of money intended to do God’s work, it was money that was only making the merchants rich. There is a fine line between churches ensuring that there is enough for good work to be happening and workers and families are cared for, and the pursuit of financial gain, but it is a line that needs to be clearly defined and held.

There is no easy solution for this. I’ve sat through the conversations about financial struggles with no end in sight. I’ve heard pastors and others in ministry talk about whether or not they can keep their doors open. But the American Church cannot continue to serve two masters. The Church cannot be a place where abusers of the Gospel are protected and raised up and those who speak out against those abuses are marginalized and silenced. It cannot continue to seek security in political and financial gain while pushing away those seeking the reassurances that are only available in Christ. It cannot continue to punish those who speak the truth in an effort to avoid institutional collapse.

Because ultimately, if it hurts Christ’s mission on earth, we should have no part of it.