Last October, InterVarsity, a Christian college ministry with chapters on 4,701 campuses, directed staff members to resign if they didn’t believe in their hearts and confess with their lips that gay sex is a sin.

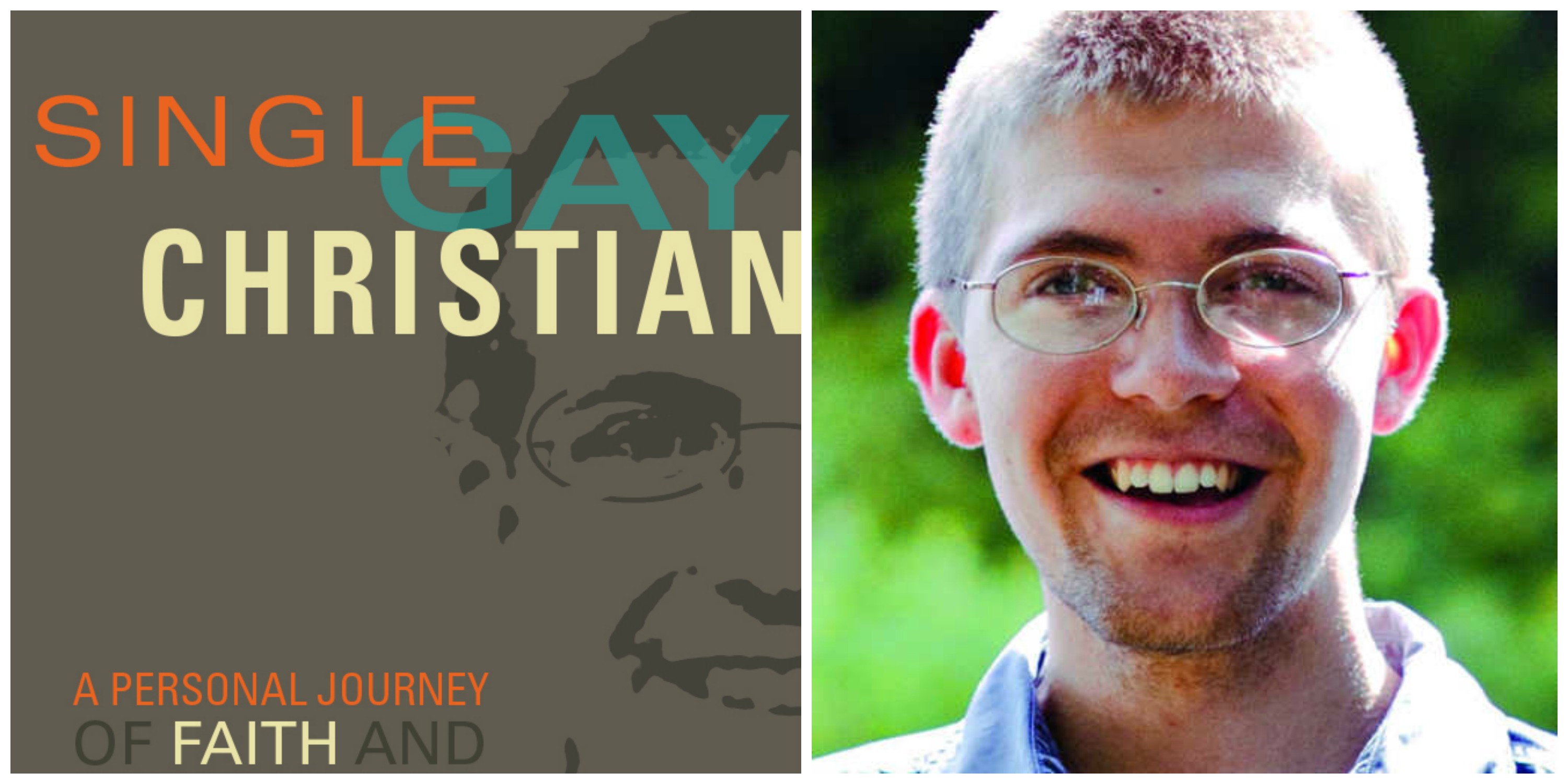

This week, InterVarsity’s publishing house just released a book by a gay, celibate, evangelical worship leader. Gregory Coles, the 26 year old, tall, blond, blue-eyed author of Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity, models InterVarsity’s vision of how a gay Christian should think and act.

Yet the book — winsome, literate, funny, vulnerable, and wholesome — ultimately undermines InterVarsity’s sectarian wall-building. “Chastity,” writes G.K. Chesterton, “does not mean abstention from sexual wrong; it means something flaming, like Joan of Arc.” Girded with a chastity belt and wielding the sword of scripture against affirming theologies, Coles serves InterVarsity’s agenda by torching leftist caricatures that a celibate life is necessarily repressed, self-hating, and unhealthy. But in a flash of fabulous humility at the end of the book, he also sets a match to the dogmatic certitude that fuels InterVarsity’s divisive edict. Throughout history, saints have been aberrant, unpredictable, and reconciling. Greg Coles is the saint we all need now.

Coles would probably object to the title “saint.” He writes, “I’m not larger than life . . . I’m just a human being.” Yet the New Testament uses the word “saints” (holy ones) to describe ordinary Christians who give themselves wholly to God. Contrary to the popular stereotype, a saint isn’t sinless. “A saint,” writes Christian contemplative Thomas Merton, “is not someone who is good but who experiences the goodness of God.” In encountering and writing about the goodness of God, Coles excels.

In spite of Coles’ undeniable pain — he confesses that “loneliness never stops bleeding” — he delights in God and seems to know Jesus in the biblical sense. The poet John Donne tells God that he will never be chaste “except you ravish me.” Coles writes as a man razed, overthrown, grinning shyly, and smoking a cigarette. Delivering on his promise to write the story of someone “in love with Jesus,” he recounts his love affair with Jesus in all its arguments, joy, and passion. “I’ve known love . . . in the moments of silence and long solitary walks as the presence of God surrounds me like a vapor, filling my lungs, racing through my veins, throbbing in my heart.”

With God as his heartthrob, Coles’ celibacy is a variety of queer love. Queer enough to make both liberals and conservatives squirm.

Christians who find themselves bi, trans, or even pan-ideological will enjoy the way Coles queers liberal orthodoxy. He makes a classically liberal move as he critiques the way capitalism teaches us to understand bodies. But his critique also challenges the liberal presuppositions underwriting sexual permissiveness. His body, he reports, is not a bundle of needs that must consume scarce goods, services, and sex in order to be sated. Rather, his ongoing intercourse with the Trinity supplies him with an abundance that he can pass on to others.

For any cis-liberal, Coles’ view that gay sex is sin will be hard to take. In support of his perspective, he doesn’t resort to any fancy theological abstractions about the teleology of bodies or their nuptial meaning. Rather, he poses the question saints often ask: If love doesn’t cost anything, what is it worth? In the midst of Western entitlement and affluence, he reminds us that Christian love requires picking up a cross. He wonders — given the plainest sense of scripture — why his gay love of the divine and others wouldn’t cost the difficulty of celibacy.

Before conservatives can crown him with a saintly halo, however, Coles bores holes into the wall of evangelical certitude with his final chapter. Having turned onto the sexuality highway and faced into the daunting headlights of most everyone going the other way, Coles remains unflinchingly humble about how much any of us can truly know.

Though Coles perceives that the Spirit of God is asking him (a white man of privilege who came from a family rich in love) to give up sex in order to love widely, he acknowledges that others may be hearing the Spirit say different things to their hearts. When one of Coles’ friends asks him if he ever worries about being wrong, Coles replies, “Of course. I’m human. I could be wrong about everything.” Then Coles tells his friend to test his beliefs and weigh them against the Bible.

It’s not that Coles is a relativist. Rather, like any good saint, he reminds us of which truths are important, when they need to be remembered, and how they need to be acted upon. When his friend goes on to ask, “What if I get married to another guy?” Coles responds, “Then I’ll still love you. And I hope you’ll still love me too. And I’ll pray that both of us fall more desperately in love with Jesus, that we keep becoming more willing to give up everything for the sake of the cross.” Rather than pressing a single “truth” that will cause fracture and alienation, Coles chooses to embrace a greater truth — that Christians are called to love one another in spite of disagreements (per John 15:12-14).

Coles’s generosity in following this more difficult path of persevering love is a stark counterpoint to InterVarsity’s decision to separate in the face of disagreement. In InterVarsity’s statement about the drama, vice president Greg Jao says that InterVarsity’s stance stems from “beliefs about Scripture” and its interpretation. Yet Coles’ posture more closely mirrors the commandment of Jesus to “love one another” (John 15:17).

To paraphrase novelist Kurt Vonnegut, beliefs are like badges; we wear them to show to whom we belong. InterVarsity is wearing the “gay sex is bad” badge to mark itself as part of the tribe that regards scripture as authoritative and truthful.

Scripture, however, is not an ancient moral Wikipedia in which one types in a topic and gets the right answer. Rather, scripture is the unfolding story of God’s surprising and good work in the world. Most Christians now agree (in spite of verses withstanding) that the deep story of scripture embraces uncircumcised Gentiles, celebrates women as equals, critiques slavery, and reconciles races. Could it be that the biblical story’s deepest logic also welcomes gay people?

Galatians, for instance, Martin Luther’s favorite New Testament book, is much on the mind of Protestants during this 500th anniversary of the Reformation. In Galatians, the Apostle Paul, a former zealot for the law, notices the Spirit’s work among uncircumcised Gentiles and angrily denounces the Christians who impede God’s work by insisting on their circumcision. He does this in spite of that fact that Hebrew scripture predicted that Gentiles would be added to Israel as part of God’s people — but through submitting to circumcision and the law of Moses (Ex 12:48, Isa 2:2-3). Paul exclaims, “I wish [those insisting on circumcision] . . . would castrate themselves!” (Gal 5:12). Since the Spirit is clearly at work in partnered gay people — just as the Spirit was working in Gentiles during Paul’s time — perhaps gay Christians do not need to submit to laws that serve as boundary markers? Perhaps these divisive boundary lines are as obsolete as the practice of forced circumcision for converts?

Coles’ response to his friend is the badge for Christians that Jesus proposed: “By this all will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). Non-believers won’t be impressed by a religious group that expels members in order to be “right.” They might be interested, however, in a group of people who vehemently disagree and yet seek to love each other anyway. Coles reminds Christians of the deeper truth that the most enduring badge of Christianity is the cross — which is demonstrated in costly love. For as Jesus taught, “Greater love has no one than this, that one lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13).

Gregory Coles is God’s good gift to a polarized world that needs people who practice the virtues of unity and peaceableness. May InterVarsity’s leadership accept his example into their hearts and confess with their lips that loving across differences is God’s good and holy work among us.

Tim Otto is a gay pastor and author of Oriented to Faith: Transforming the Conflict Over Gay Relationships. He may be followed at @Tim_Otto.