When I was a kid I’d go to mass on Sundays and hope that this week’s eucharistic hymn would be my favorite:

When I was a kid I’d go to mass on Sundays and hope that this week’s eucharistic hymn would be my favorite:

We remember how you loved us to your death

And still we celebrate, for you are with us here.

Our shared memory in the mass was indirect; no one in the room had actually been present at the crucifixion of Christ. But we remembered it nonetheless, because we had (or our parents had) joined ourselves to a faith tradition built on that central event: a living God, sacrificing himself on our behalf, never lost to us but willing to be lost for us. With that sung we would take communion, the body and blood of our Lord, and return to our pews.

Probably because this sacrificial act at the heart of Christianity has so pervaded Western culture, we prize and celebrate sacrifice, regularly and creatively remembering those who have “made the ultimate sacrifice.” We don’t celebrate military exploits in the way that ancient Greek and Roman poets did; rather we mark moments such as Veteran’s Day (in November) and Memorial Day (this weekend) by taking our hats off our heads and putting our hands to our hearts, standing in sober silence at the thought of someone taking bullets for us, firing weapons for us, paying the ultimate price for us. There’s the Savior of the world, in the cultural imagination of the West, and then there’s the Soldier by whose stripes our freedoms and rights are vouchsafed.

I don’t have a military background. I have some uncles who long ago fought overseas, but I have an equal number of extended family members who fought against American military actions all over the world. My dad spent some time at the United States Military Academy at West Point, which captured my imagination for a while as a kid (Edgar Allan Poe spent some time there too, in case you were wondering), but I never seriously considered military service or dedicated serious time to reflecting on the military. Memorial Day has never meant all that much to me, to be honest.

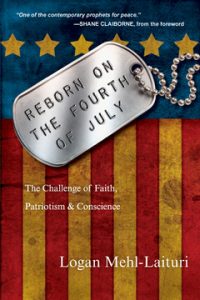

I feel a little differently anymore. That’s due in part to the fact that my country has been at war for more than a decade, much of that time on more than one front, and seems to keep a running list of future targets, just in case. As far away as the U.S. military travels, it’s never not close to home anymore. I’m particularly conscious of the state of war and the challenges faced by military personnel and veterans thanks to Logan Mehl-Laituri, whose book Reborn on the Fourth of July is now in print. Logan served in Iraq during our most recent war there, and sought to return for a second tour as a noncombatant conscientious objector, thanks to a conversion of conviction along the way. His request to return to Iraq as an NCO soldier was denied, and he was later honorably discharged. Now he advocates for veterans and speaks broadly on issues of faith and nationalism and militarism. I edited Logan’s book, which opened my eyes in new ways not only to the cost of war but to the cost of conviction. I may pray and even fight for peace (whatever that looks like), but the greater commandment from the Prince of Peace is to dignify every person (whether enemies foreign and domestic, or ideological opponent) as created in the image of God, and to love our neighbor (whether across the trenches on the battlefield or in military hospitals or on picket lines outside of a NATO summit) as ourselves.

I feel a little differently anymore. That’s due in part to the fact that my country has been at war for more than a decade, much of that time on more than one front, and seems to keep a running list of future targets, just in case. As far away as the U.S. military travels, it’s never not close to home anymore. I’m particularly conscious of the state of war and the challenges faced by military personnel and veterans thanks to Logan Mehl-Laituri, whose book Reborn on the Fourth of July is now in print. Logan served in Iraq during our most recent war there, and sought to return for a second tour as a noncombatant conscientious objector, thanks to a conversion of conviction along the way. His request to return to Iraq as an NCO soldier was denied, and he was later honorably discharged. Now he advocates for veterans and speaks broadly on issues of faith and nationalism and militarism. I edited Logan’s book, which opened my eyes in new ways not only to the cost of war but to the cost of conviction. I may pray and even fight for peace (whatever that looks like), but the greater commandment from the Prince of Peace is to dignify every person (whether enemies foreign and domestic, or ideological opponent) as created in the image of God, and to love our neighbor (whether across the trenches on the battlefield or in military hospitals or on picket lines outside of a NATO summit) as ourselves.

We love our neighbors best, perhaps, when we remember them; I daresay that remembering is the first act of love toward a person. Remembering literally means to piece them back together, to reattach them to ourselves and ourselves to them. Soldiers, fallen and discharged and active alike, are first and foremost our neighbors; whatever your convictions about war in general or particular wars in particular, soldiers have, by entering into our conflicts on our behalf, loved us as themselves. Along the way some of them have been dismembered; some of them have been lost. This Memorial Day let’s rediscover and re-member them, even as we pray for the Prince of Peace to deliver us from our enemies and, I daresay, ourselves.

***

See Logan discussing his book here.

Learn about Logan’s organization, The Centurion’s Guild, here.

Read or contribute to the Wall of Remembrance here.

—-

David A. Zimmerman is an author and editor. His booklet The Parable of the Unexpected Guest, a thought experiment for discipleship and evangelism, was released by InterVarsity Press in September 2011.