Don Golden interviews Red Letter Christian friend and renown Old Testament scholar, Walter Brueggemann, on his book, God, Neighbor, Empire: The Excess of Divine Fidelity and the Command of Common Good (Baylor University Press, 2016). This is the first in what will be an occasional series.

DG: The Bible confronts empires from Egypt to Rome, each, as you say, “amid great concentrations of wealth and power.” How is the biblical pattern of empire at work today?

WB: Until recently it was U.S. domination. But I think now it’s the oligarchy of concentrated wealth…the network of the wealthy and powerful in the U.S. and around the world who basically outflank or control governmental structures. The control of technology is key, but more importantly is the control of imagination. So that it becomes impossible to imagine any social reality outside the scope of what that system offers.

DG: A new world is not possible.

WB: That’s right. And the biblical tradition and particularly the prophetic tradition is an act of imagining outside that closed system.

DG: You call that social reality, “the patterns of political economy.”

WB: Right. The political economy of imperial systems is always extracting wealth from vulnerable people and transferring it to powerful, wealthy people.

The recent House action about health care is exactly that transfer of wealth: tax breaks of trillions of dollars at the expense of the vulnerable who will not have health care. I think you can see the extractive system.

It has occurred to me that tax collectors in the New Testament were Jews who had forgotten that they were Jews and had signed on with the Roman system which was exploitative. So in Luke when Jesus talks with Zacchaeus and calls him “a son of Abraham,” he invites Zacchaeus to reaffirm his identity in the Abrahamic tradition and to distance himself from the extraction system of Rome. The truth is that the imperial system is so powerful that many of us have largely forgotten our true identity in this alternative tradition.

DG: So there’s wealth extraction and transfer from the vulnerable to the wealthy. Then you point to commoditization and violence as two more features of empire at work today.

WB: Commoditization is the reduction of everything and everyone to a marketable product. The identity of individual persons is forgotten. They simply become a pawn in the traffic of commerce. And when everything and everyone is a tradable commodity, then anyone with money and power can call the shots. The more vulnerable you are the more disposable you are.

The rhetoric of the extreme Right about health care is a statement that, “If people can’t afford health care, they don’t get health care. And if they need to die, then they need to die.” Which is a radical notion of dispensability.

DG: Then violence. You do what you must to protect that system.

WB: The system itself becomes a justification for violence. The deep, old tradition of being chosen people is operative in this. If you are successful and powerful, you obviously are chosen and entitled and privileged. And people who are left behind or excluded are obviously the unchosen, and they’re not entitled to anything.

DG: A song by Rage Against the Machine says, “Jesus blessed us with his future, and we protect it with fire.”

WB: Haha, that covers it!

DG: How can we resist “the patterns of political economy?”

WB: The Hebrew word for steadfast love is hesed. I translate it as tenacious solidarity. God is in tenacious solidarity with Israel in the Old Testament, particularly with widows and orphans and immigrants and poor people. God is tenaciously in solidarity with them and with the community that participates in God’s faithfulness. We are called to be in tenacious solidarity with the vulnerable which then leads to all kinds of actions and policy formation out of this tenacious solidarity.

DG: As a Calvinist, you believe in what government can and should do. I’m afraid I can’t conceive of a pathway to a just government. Are we approaching some kind of break, some kind of collapse, like the apocalyptic scriptures describe?

WB: I share that sense of the danger we are in. A hymn by John Calvin says, “My hope is in no other save in thee alone.” Yes, hope is beyond all social governmental structures. But radical hope ought to lead us to community organizing on the bet that God works in the world through the solidarity of the excluded. Radical hope beyond social governmental structures has to be engaged actively in the construction of new social governmental structures. We have to avoid escapism.

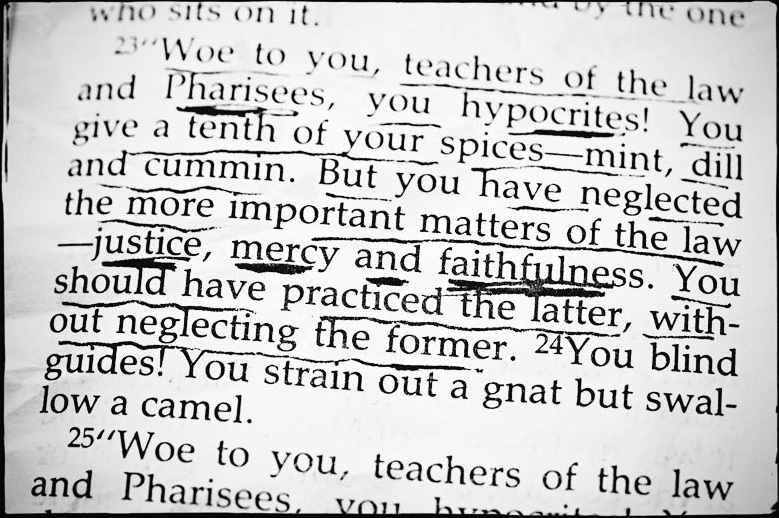

DG: Your book highlights Matthew 23:23 in the struggle against empire where Jesus confronts the hypocrisy of a scrupulous religion that denies “the more important matters of the law—justice, mercy, and faithfulness.”

WB: That verse occurs in Matthew’s “woe” oracles. In the book of Proverbs, woe meant “sadness over loss and death.” I translate it here as “big trouble comin.’” Big trouble comin’ to those who put their energy into the facades of a fake society. Big trouble comin’ to the keepers of a fake economy. Big trouble comin’. It’s inevitable.

You don’t have to believe in the swooping in agency of God. You just have to recognize that creation is morally ordered in a way that cannot be outflanked.

When we are wealthy and powerful, we can engage in the illusion that we are beyond accountability. American exceptionalism has invited us to think that we don’t have to answer to anybody. Matthew 23 is exactly a statement that, “Oh yeah, everybody is accountable and, sooner or later, its comin.’” And your statement that we are at the edge of an apocalyptic moment – yes, the chickens are coming home to roost.

Big trouble comin’ is hope for those on the underside. Hope that this phony fabric of a political economy is simply unsustainable, because Jesus declares that the way of the world is overcome.

An astonishing thing to say.