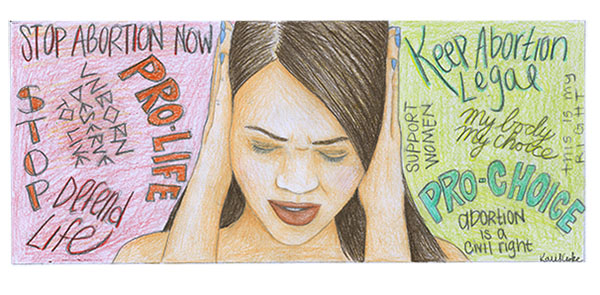

The first time someone called me a “baby killer,” I was 18 and shocked by the invective. I’d not yet developed a stance on abortion, one way or another, and was incredibly naïve about what abortion entailed and why people might oppose it. Yet, my Christian college classmate assumed that because I was a Democrat I would believe killing babies was morally acceptable, preferable even. He was clearly naïve as well.

This week, I was called a baby killer again, this time on social media, when a stranger accused me of having no soul and murdering babies. I had suggested that abortion discussions are rarely nuanced, including the current outrage directed at a failed Virginia law regarding abortion later in pregnancy. Asserting that women in a situation covered by the law are most often devastated by the loss of a much wanted child, and questioning what decision I might make, turned me immediately into a proponent of infanticide.

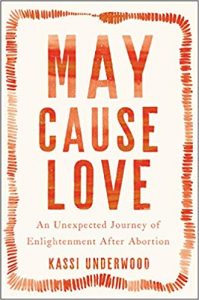

Apparently, there is no room for nuance in a debate pitting presumed baby killers against woman haters. And also, no room to understand the humanity of women involved in heart-breaking choices about their own lives — and the lives of their children (born and unborn) as well. Still, when I read Kassi Underwood’s 2017 memoir, May Cause Love: An Unexpected Journey of Enlightenment After Abortion, I felt sure discussions about abortion might begin to shift, from unproductive arguments based on black-and-white ideology to something far more complex.

In May Cause Love, Underwood narrates her unfolding spiritual journey following an abortion at age 19. The memoir unflinchingly chronicles Underwood’s lonely attempts to discern what she should do with her pregnancy; the painful abortion itself, also lonely; and the months and years that stretched out after the procedure, when isolation, shame, and sadness became Underwood’s constant companions.

Beautifully written, May Cause Love offers no dogmatic statements about what people should believe about abortion, but instead uses Underwood’s experience to explore questions about where God stands in the midst of pain — and how women’s stories about abortion have been co-opted for political purposes, creating a cycle of shame and misunderstanding and despair that does little to address why women have abortions. Underwood’s memoir is a sacred and grace-filled tale of how loneliness can be redeemed by loving communities who support women, no matter the choices they make.

Beautifully written, May Cause Love offers no dogmatic statements about what people should believe about abortion, but instead uses Underwood’s experience to explore questions about where God stands in the midst of pain — and how women’s stories about abortion have been co-opted for political purposes, creating a cycle of shame and misunderstanding and despair that does little to address why women have abortions. Underwood’s memoir is a sacred and grace-filled tale of how loneliness can be redeemed by loving communities who support women, no matter the choices they make.

Turns out, having a nuanced narrative about abortion can be problematic, in and of itself. Narratives that don’t meet our baby killer or woman hater polarity are unwelcomed by a journalism industry too aware that division and moral outrage sells.

In spring 2017, Underwood’s memoir was published by HarperOne, a subsidiary of Harper Collins, one of the top publishing houses in the U.S., suggesting that complicated spiritual memoirs about abortion might be ready to go mainstream. Underwood’s narrative approach seemed unapologetically undogmatic, her story personal and compelling and a reminder that real-life women, experiencing life-ending abortions, can grapple with complicated feelings about their abortions — feelings that cannot easily fit within the usual pro-choice or pro-life paradigm our public discourse offers us.

In the months following the publication of May Cause Love, a handful of journalists pitched reviews of the memoir to Christian publications and to feminist ones. Although the book was reviewed in a few online publications, these pitches were predominantly ignored, the nuances of the memoir seeming unwelcomed by conservative and progressive places alike. Sometimes, journalists working on reviews for Underwood’s memoir were ghosted in the editorial process, as if the very topic Underwood was covering — women’s complex experiences with abortion — was taboo, not ever to be mentioned in any context, professional or otherwise.

Such a response essentially proved the very point Underwood was hoping to make in telling her story: that unless women’s encounters with abortion fit the black-and-white narratives we’ve already heard countless times; we don’t want to hear them. An underlying theme in Underwood’s story is that when women are offered the chance to tell their stories, they are offered a chance to heal; and so until women can tell their stories, no progress will be made in the abortion debate. People will remain entrenched, their beliefs unchanged, and fundamentally, both women and children will continue to suffer.

READ: Why Abortion Should Not Be Politically Decisive for Christians

“The fight right now is extremely superficial and everybody’s trying to stay ‘on message’ and ‘on brand,’ which means nobody is saying anything new,” Underwood told me recently. “We’re trying to solve a mind-bogglingly complex issue with slogans and messaging, and it hasn’t worked after decades of trying. The impact is, millions of people who’ve had abortions feel isolated and misunderstood.”

“One in four women will have an abortion in her lifetime,” Underwood said. “We haven’t begun to untangle the web. The experience of abortion is wrapped up in layer upon layer of patriarchy, including patriarchy masquerading as feminism.”

Underwood had hoped May Cause Love could change the conversation. When the book was released, just months after Donald Trump’s inauguration, it was clear readers weren’t looking for nuance, but were seeking places to confirm their rage in a deeply polarized cultural climate. According to Underwood, “My book didn’t make enough noise, in part because I wasn’t taking a side in the debate. I was talking about attaining peace of mind and community in a time when moral outrage was on trend.”

Indeed, recent public discourse surrounding abortion suggests there has been an intensification of moral outrage, rather than any attempt to find common ground. January’s March for Life in Washington D.C., the remarks there by President Trump and Vice President Mike Pence, and the conflict between adolescents following the march and an Indigenous elder all fueled online discussions about what it truly means to affirm the sanctity of all life. In the same week, the signing of a Reproductive Health Act in New York state enraged some right-to-life advocates, who believed the law would encourage mothers to abort their children in the late stages of pregnancy.

These events have done little to open space for nuance and authentic conversation about abortion. Instead, adversaries on all sides of the debate fail to listen to those at the center of this controversy: women who have had abortions.

READ: Evangelical Women & Men Call for A Pause on Culture War

Even articles purporting to change the dynamics of the issue, suggesting a way forward, offer little by way of women’s lived experiences. See, for example, this recent article in the New York Times, in which a man suggests his pro-life identity matters in a “throwaway culture” where a pregnancy can be ended without a second thought, as if babies are just another disposable item. Yet the writer does not offer any woman’s perspective on what her abortion actually entailed, nor does it acknowledge the complicated decision-making process women report going through when faced with having an abortion.

Many of those who support reproductive rights have also promoted women’s abortion experiences as an unalloyed choice that has few emotional or medical drawbacks, and so have little space for a memoir like Underwood’s, which acknowledges the pain, physical and otherwise, that accompanied the choice she made. Amelia Bonow’s 2015 campaign #ShoutYourAbortion called on women to tell their stories about abortion as a way to normalize it, and the resulting website features women talking about abortion in wholly empowering terms. This winter, writer Lindy West and Emily Nokes collected these and other stories in the book Shout Your Abortion, with a mission of reducing the stigma that can come with abortion. “Abortion is common,” West wrote in 2016. “Abortion is happening . . . Abortion is a thing you can say out loud.”

In some ways, Bonow and West are advocating an approach to storytelling that seemingly makes space for women’s varied experience about abortion. Underwood tells me that she would have been “over the moon” if Shout Your Abortion had been published in the aftermath of her abortion. “It’s high vibe, relevant, and feminist,” Underwood said, “but at the same time, I think I would have felt an eerie sense of aloneness alongside of my joy, because my story isn’t quite as clear and unmitigated as Lindy and Amelias’. And that was a big part of my feeling of isolation. I could talk about my abortion, but I couldn’t talk about the confusing mixture of emotions and war inside of me.”

May Cause Love addresses these tensions well and is an astounding memoir, because Underwood provides a voice rarely if ever heard in abortion discussions. As Underwood’s publishing journey itself reveals, though, such voices are unwelcomed by mainstream and Christian audiences alike, who are looking for their biases to be confirmed, rather than challenged.

And, of course, some anti-abortion activists might argue that women’s stories mean little when babies’ lives are at stake. But attempts to shame women into different choices — by yelling at them in front of abortion clinics, threatening or enacting violence, even posting graphic pictures on social media — fail to offer any way forward in this discussion, because those acts dehumanize and silence women, making them into public enemies worthy of scorn, baby killers rather than people often faced with untenable life choices.

READ: Not Pro-Life or Pro-Choice, but ‘Pro-Voice’

In May Cause Love, Underwood highlights a compassion-based organization called Exhale, which labels itself as “pro-voice,” by providing space and resources for women and men with abortion experiences to simply tell their stories, to be heard, and to process what has happened without shame or judgment.

Exhale believes that when the stigma of abortion is removed, allowing people to converse with friends and family about their experiences with abortion, they will feel less isolated as they wrestle with the decisions they must face, and they will also find a caring community who will love them, no matter what. This kind of support, Exhale believes, could change the shape of public discourse about abortion altogether.

Until women are free to talk about the choices they have to make, Underwood explains, we will not resolve the critical impasse that says people fall into one of two categories: either baby killers or woman haters.

“Elevate the voices of people who have abortions,” Underwood says, a point that resounds clearly in her memoir and in the work she’s done to make space for others to tell their stories, too. But those complex, nuanced narratives won’t be told so long as media companies refuse to promote them — and so long as consumers, activists, all of us who care about this issue, refuse to hear.