Introduction

An Invitation to Love Life

I grew up in the heart of the Bible Belt, in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. I fell in love with Jesus there. Sunday school, youth group, Young Life, Fellowship of Christian Athletes (I wasn’t even really an athlete)—I did it all. I am a child of the church. My grandparents were Southern Baptists, but Mom and I found a home among the Methodists. Before long, I wanted some of the Holy Ghost fire and the miracles and wonders of the Pentecostals, so I joined the charismatic movement. When that got a little funky, I leaned into the deep roots of Catholicism for a while. I guess you could say I’m a bit of a spiritual mutt, but all of it shaped who I am today.

My political and social imagination was also shaped by the culture wars of the 1980s. I helped lead the See You at the Pole campaign, where high school students gathered at their school’s flagpole to pray for our nation before heading into classes. I was ready to go to jail if they (whoever “they” were) told us we couldn’t pray in public school.

As my theology grew over the years, I learned to appreciate the treasures of many different traditions of Christianity, to savor the meat and spit out the bones. I also began to see some of the church’s blind spots—both the theological ones and the practical ones—particularly when it came to our value for life.

I passionately embraced the label “pro-life,” but my concept of what it meant to be pro-life revolved almost entirely around ending abortion. Ending abortion was as fundamental to my faith as being baptized or taking communion. I did not believe you could really be a Christian and not take a stand against the horror of abortion.

I distinctly remember learning to debate and loving the thrill of trying to argue someone into the ground. I can even recall, like it was yesterday, making the case in my twelfth-grade English class that abortion is murder and murderers deserve the death penalty, so why aren’t we arresting abortion doctors and putting them on trial? I had all the Bible verses that I thought made the case crystal clear. I even thought about becoming a lawyer.

But my crystal-clear case started to crack a little bit when I realized I was justifying one form of violence (the death penalty) as punishment for another (abortion). And it wasn’t too long before I began to see more contradictions, both in the church and in myself. For example, while I was learning to defend my faith with Lee Strobel’s book The Case for Christ, I was also learning to defend guns, war, and the death penalty. The more I leaned into Jesus, read the Gospels, and reflected on the Sermon on the Mount, the more conflicted I felt about many of my political positions.

I began to realize that it would be more accurate for those of us who consider ourselves pro-life to call ourselves “pro-birth” or “anti-abortion.” Sometimes we have been more concerned with life before birth than life after birth. It is a strange thing to live in a world where we can be pro-military, pro-guns, pro-executions, and still say we are pro-life so long as we stand against abortion. But, alas, that is where we find ourselves.

When I think back to those years in high school when abortion consumed so much of my energy, I realize that I had lots of ideologies, but few if any relationships with people whose lives were impacted by those ideologies. Ideologies alone don’t require much of us, and mine hadn’t required much of me.

I had a lot to say about abortion, but eventually it occurred to me that I couldn’t think of a single person I knew who had actually had an abortion, or at least anyone who felt comfortable telling me about it. In retrospect, this is understandable since I had said out loud that I thought abortion doctors deserved the death penalty. As is too often the case, I was good at talking about issues, but not as good about having compassion for the people directly affected by the issues.

Sometimes our theology or our political opinions become an obstacle to love rather than a conduit of love. And that is a problem.

We cannot talk about issues while avoiding the people who are affected by them. We cannot talk at each other; we must talk with each other.

A Lovely Question

This book is not just about issues. It is about people. It is about asking, What does love require of us? Ideologies do not demand much of us, but relationships do. “What does love require of us?” is a lovely question because it is a call to action.

Asking that question changed everything for me because what love required of me was more than a saying on a bumper sticker, a T-shirt, or a yard sign. It required proximity and relationships. It required drawing near and leaning in to those who had been impacted by the issues. In our neighborhood in North Philadelphia, gun violence is more than statistics; it has names and stories and tears. We have murals and memorials on nearly every corner to honor the lives lost to guns. Gun violence is about the three-year-old hit with a stray bullet on Malta Street. It’s about the mother who collapsed onto the sidewalk when she got news her little boy had been killed. To me, gun violence is so much more than talking points because it affects neighbors whom I love. That’s why I’m inviting you to join me in asking this question about every issue: What does love require of us?

It’s the same with the death penalty. For me, the death penalty is not just a political issue, it’s a reality that nearly took the life of Derrick Jamison, one of my close friends who was sentenced to die for a crime he had nothing to do with. He spent two decades on death row, had six execution dates, and was hours from execution when he was finally proved innocent. Listening to Derrick describe what it was like to watch his friends—more than fifty of them—be killed by the state, one by one, and to constantly wonder whether he would be next, does something to you. When you hear a mother say that the first time she kissed her son in thirty years was after his execution because they were not allowed to have contact visits, it does something to you.

When I think about war, it is no longer something I pontificate about in an abstract sense. It is about the children I held in the Al Monzer Pediatric Hospital in Baghdad. Their bodies were riddled with fragments from bombs dropped on them by the US during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. I’m still willing to talk about “just-war theory” with people who care about that, but what changed my heart was not just losing an argument, it was seeing the devastation of war firsthand. I became convinced that love doesn’t do that to people.

What has changed me over the years is not slogans or rallying cries but listening to my immigrant neighbors, visiting refugee camps, sleeping on dirt floors, and biking along the US-Mexico border to talk with refugees and asylum seekers. These are the things—or to be accurate, these are the people who have caused me to wrestle with the question, What does love require of us? What does love require of me?

I am still a work in progress, and I don’t pretend to have answers to all of the questions that will arise in the pages that follow, but this I know for certain: Being in proximity makes a difference. Relationships make issues real and complicated and personal. Relationships move us from ideology to compassion. We can’t love our neighbors if we don’t know them. And once we are proximate, love requires us to take action, to stand up for life in tangible ways.

Pro-Life for the Whole of Life

Back when I was trying to sort out the contradictions of what it means to be pro-life, I eventually bumped into this idea of a “consistent ethic of life,” the conviction that all of life—from womb to tomb—matters. To have a consistent ethic of life is to be comprehensive in our advocacy for life and to refuse to think of issues in isolation from each other. It is a fundamental conviction that every person is sacred and made in the image of God. It requires pursuing whatever allows people to flourish and fighting everything that crushes life. That means that all these difficult issues—the military, guns, racism, the death penalty, poverty, and abortion—are connected, and we need a moral framework that integrates them. That’s what it means to be pro-life for the whole of life.

For some, a consistent ethic of life is nothing new. Catholics have used the language of a “seamless garment” woven of all the issues. For centuries, Anabaptist Christians have maintained a commitment to life and a passion for nonviolence. The early Christians, as we will see, had a consistent ethic of life. They were a force to be reckoned with, speaking out against every manifestation of violence in their society. They spoke against war, domestic violence, capital punishment, and they spoke against abortion. They even spoke out against gladiator games, a popular form of entertainment in the Roman Empire and one of the particular ways our human infatuation with violence expressed itself in their culture.

Christianity’s first three centuries were strikingly and wonderfully pro-life in the best and most encompassing sense of the word. And today, this idea of a consistent life ethic is resonating with a whole new generation that has grown tired of death in all of its ugly manifestations.

I want to invite us to love bigger, to extend the same passion that many of us have for one issue to all of the issues. We’ll be building a broad, firm foundation that helps us be advocates for life comprehensively, without exceptions. We won’t minimize the conversation about abortion, which we will address. Instead, we’ll situate that conversation within an expansive, passionate ethic of life that includes other issues. We care about issues because behind the issues are real people.

I must confess that I wish some of my conservative friends cared as much about life after birth as they do life before birth. And I wish some of my progressive friends saw abortion not just as a rights issue but also as a life issue, a moral issue. Then we might do a better job at reducing the number of abortions.

So this is a book about life. And it’s a book about love. We are asking the most important question of all: What does it look like to love God with our whole heart and mind and strength, and to love people as ourselves—without exceptions?

My primary ambition is not to reclaim the pro-life label. Instead, my hope is that you and I will embrace a robust ethic of life. I want this deep, heartfelt conviction that every person matters to God to impact how we think—theologically, politically, socially, morally—about a whole range of issues.

So let’s get to it. This book is divided into three parts. Part 1 helps us build a foundation for a better ethic of life by looking to Scripture, Jesus, and the early Christians for inspiration. Part 2 is an honest look at where the foundation for life began to crack over the centuries. And I’ll warn you, this part of the book is pretty heavy and heartbreaking, but the truth sets us free. So we’ll take a closer look at the Crusades, slavery, colonization, and other ways Christians and the church have failed to be champions of life. Finally, in part 3, we’ll explore what it will take to repair the cracks in the foundation of our ethic of life and how we can be a force for life and for love in the world. All along the way, we’ll be asking, What does love require of us?

It’s time to rethink how precious life is so we can reclaim the sacredness of every human being.

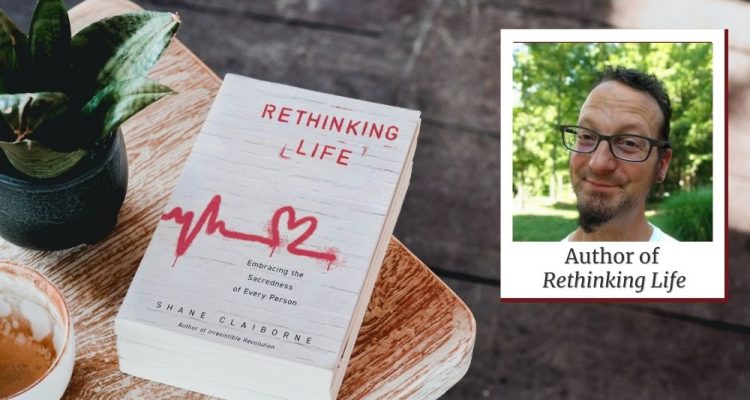

Excerpt from Shane Claiborne’s Rethinking Life, Zondervan Books, Published February 7, 2023, Used by permission.