Scripture tells the story of a 12-year-old Jesus who slipped off without the courtesy of a quick word to Mother Mary or Stepfather Joseph about where he was going or how late he was staying out. His parents assumed that he was moving with the group, as planned, back home to Nazareth at the end of the Passover celebration, traveling with others, not too far away. Eventually, they realized that Jesus was not on his way home at all; he had stayed behind in the city of Jerusalem. It took three whole days before his earthly parents eventually found him in the city’s Temple.

Mary issued the age-old, long-repeated refrain of maternal worry: “Son, why have you done this to us? Your father and I have been very worried, and we have been searching for you.”

Jesus responded, “Why did you have to look for me? Didn’t you know that I would be in my Father’s house?” The tween Jesus offers a response that amounts to I had to do what I had to do and I had to go where I had to go. I’m called. Don’t you get it?

Of course, his earthly parents really didn’t get it.

Jesus is neither the first nor last adolescent to worry his mother with seemingly inexplicable (to her) behavior. The developmental processes of adolescence – rapid growth, self-discovery, identity formation, boundary-pushing, vocational discernment and more – are beautiful, fruitful, creative and powerful to behold and often deeply aggravating to grown adults. This is not a sign of youth being “bad” or “broken”; they’re doing what adolescents are created to do.

Mary’s response to Jesus provides a useful model: the family returned home together and Mary “kept on thinking about all that had happened.” Those rooted in the Christian tradition know that Jesus ultimately gives Mary far more to think about than just this brief stint as a juvenile runaway: Mary’s son will have a truly unique, world-changing destiny. But those of us who parent, teach, mentor or otherwise care for mere mortal children and teens, can still learn from Mary’s practice of pondering. Like Mary, we can take time to “[keep] on thinking about all that had happened” before we react to adolescent and childhood behaviors with knee-jerk punitive patterns. Instead of immediately launching into control-and-punishment strategies – from suspension to criminalization — we can ask real questions that explore both the presenting issue and the larger backstory. These aren’t fake questions (“How could you be so stupid as to do ABC?”) but open, curious questions (“What were you feeling and thinking at the time XYZ happened?”). Transformative and restorative justice practitioners give us abundant tools for such honest dialogue.

We have another useful theological tool, as well: grace. In the language of my own Methodist tradition: we may be on the sanctification journey, but we have not yet arrived at perfection. Grace recognizes that all of God’s children – age six, sixteen or sixty – are people in the process of formation, in the midst of becoming. Grace is especially vital to children and adolescents whose bodies and brains are changing at such a rapid rate that they are quite literally not the same people this month as they were last. Grace is the opposite of juvenile incarceration and a powerful, obvious antidote to the relentless expansion of zero tolerance policies. Grace is vital to growth.

Our institutions already know how to extend empathy and grant grace to some kids: we habitually afford grace to White children and adolescents. We wonder about the “why” of their actions without pathologizing the “who” of their persons. We assume that they will make mistakes and we treat those mistakes as opportunities to learn. We give second, third, fourth and forty-fourth chances. This is not bad. White kids and teens are growing and changing and that’s not easy. They deserve our love and compassion. But kids and teens of color are also growing and changing and that’s not easy, either. They, too, deserve our love and compassion. But it is rarely forthcoming. We simply do not provide the same grace margin to children of color that we do to White children. This is especially true for Black children.

Instead, Black children are routinely held to absurdly age-inappropriate standards and expected to perform perfection as a means of earning their survival. Consider the horrifying victim-blaming rush to defame murdered children like Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice. The Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality has detailed the adultification bias, finding that Black girls are perceived as older than they actually are and erroneously believed to be less in need of protection and nurturance. Living under a veil of hyper-surveillance and racist suspicion starts early. The US Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights has clearly documented that racial disparities in school discipline begin by preschool and persist throughout the PK-12. Recent qualitative research on Black boys’ early experiences paint a clear picture of anti-Black racism and educational harm from the outset. Both Professor Kristin Henning’s The Rage of Innocence and Dr. Monique Morris’ Pushout describe the criminalization of Black childhood and adolescence.

Even when Black children do nothing wrong, at all, they are targeted, punished and criminalized just for the fact of being Black children. Black girls’ joy, itself, is suspect, as in the now-infamous case of four adolescent girls who were strip-searched at school in Binghamton New York for seeming too happy, as though tween girls being “giddy” was somehow unimaginable.

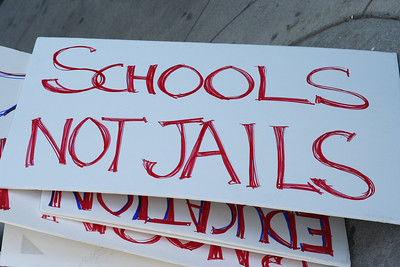

Meanwhile, the schools children attend are increasingly overpoliced and under-resourced. 1.7 million children attend schools with a police officer on site but no counselor. The presence of school-based police, often called school resource officers, increases the use of exclusionary discipline, further driving the school-to-prison pipeline.

We have heard this all before. When it comes to building safe and supportive educational spaces for children and adolescents, we know what works – and what doesn’t. But, in our collective anxiety, we don’t follow any of these best practices. We know that supportive relationships work wonders for all people and for children, especially; but we pour funding into “school hardening” strategies with no track record of efficacy while we starve counseling budgets, cut enrichment programs and lay off teachers. We know that real, commonsense gun control measures could improve public safety and save children’s lives in all the spaces they spend their days, from home to street to school; but, instead, we vote up funding for school-based police officers (SROs) despite the horrendous track record. while making only the most meager movements on gun safety.

We are not wrong to worry about gun violence. Firearms are the leading cause of death for people under 20-years-old in the United States. About three in ten of those deaths are due to suicide, one in twenty are the result of accidents, and two thirds are homicides. The New England Journal of Medicine notes that child mortality due to firearms increased by 13.5% between 2019 and 2020. The vast majority of these deaths do not happen at school. Nonetheless, it is inexcusable that children and youth in the United States are more likely to die from guns than from car crashes, cancer, injuries or congenital disease. It should shame us from our complacency to realize that our nation is alone among similar countries in this grisly statistic.

But putting more police in schools won’t help.

Robb Elementary was full of police officers. On that terrible day there were 376 officers from at least eight different departments and divisions present at the school in Uvalde. After an initial engagement, police stood by for over an hour, even as children lay bleeding to death inside the classroom, their peers making desperate, repeated pleas to 911. One officer, husband of a teacher trapped inside, did try to storm the school as his wife was dying, but he was stopped and his gun taken away. Meanwhile, at least one mother, Angeli Rose Gomez, was handcuffed by officers before she persuaded someone to release her and pulled her two children out of the building. All of this took place while police officers remained outside waiting a terrifying 73 minutes to intervene and stop the shooter. The Texas House of Representatives’ Interim Report concluded that while it was likely that most of the children died in the initial attack, “it is plausible that some victims could have survived if they had not had to wait 73 additional minutes for rescue.”

While Uvalde showcases an especially egregious response failure, school-based police did not have a strong record on stopping mass shootings prior to this summer, either. A school resource officer was on site at Mary Stoneman Douglas High School, too. As of 2021, he was facing charges for child negligence because he hid during the shooting.

Who died protecting students? A fourth-grade teacher and a football coach both jumped in front of bullets. An athletic director ran into the building, a first-grade teacher hid children in a closet and a geography teacher provided refuge in his classroom, though it cost them all their lives. A paraprofessional died holding the student she worked with in her arms while covering others with her body. Another fourth-grade teacher, finishing her 23rd year at the school, embraced students to her dying breath. This list is not exhaustive; we could keep going if we had the heart for it. All these contemporary hero-educators deserve our honor, our respect and our unrelenting efforts to end gun violence in America.

But, as a public policy matter, school-based police do not keep our children safe. The Dignity In Schools Campaign, in conjunction with the Advancement Project, Alliance for Educational Justice and NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund released clear and compelling evidence that “Police in Schools Are Not the Answer to School Shootings” after the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012 and then again after the Parkland shooting in 2018.

If school-based policing strategies were just another well-intentioned but ineffective government expenditure then we could count the pro-SRO policy trend as a disappointment but not an emergency. But school-based policing is not neutral: it increases the number of children who are pushed into the school-to-prison pipeline. Black and Native children are the most likely victims of criminalization due to America’s longstanding and deep-rooted systemic racism. Policies that harm Black students and other students of color, by definition, do not make “all students” safer – not if we think of Black students and other students of color as a real part of the student body, equally in need of protection and care. We may sing “Jesus Loves the Little Children” on Sunday morning, but if we’re willing to throw some children in harm’s way in pursuit of strategies that give no evidence of protecting any children, then who exactly is the “all” children we’re keeping safe?

The failure to see Black children as children is perhaps one of the most damning indictments of the spiritual depravity of white supremacy and anti-Black racism. This is not merely an issue for expert educators and professional policymakers; it is a profound ethical crisis that concerns us all.

What can we do? We can publicly resist false promises of security through “hardening,” oppose increases to school police budgets and continue to push back on the criminalizing of children of color. We can support key federal legislation, including: The Counseling Not Criminalization in Schools Act; The Ending PUSHOUT Act; and The Protecting Our Students in Schools Act (POSSA). Most importantly, we can work at the local level, partnering with Dignity In Schools Campaign member organizations and others, to push school boards and other decisionmakers to prioritize racial equity, stop school pushout and interrupt the school-to-prison pipeline.

12-year-old Jesus would be a juvenile status offender under today’s standards. But his mother knew better: she knew to love her child, to go home together, and to wait and sit with what she couldn’t yet understand. After all, who might any of our children live to become, if given the chance?