Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published on A Public Witness, Word and Way and is shared here with permission.

“How did someone rooted and grounded in a Baptist version of Christianity become a religious pluralist?”

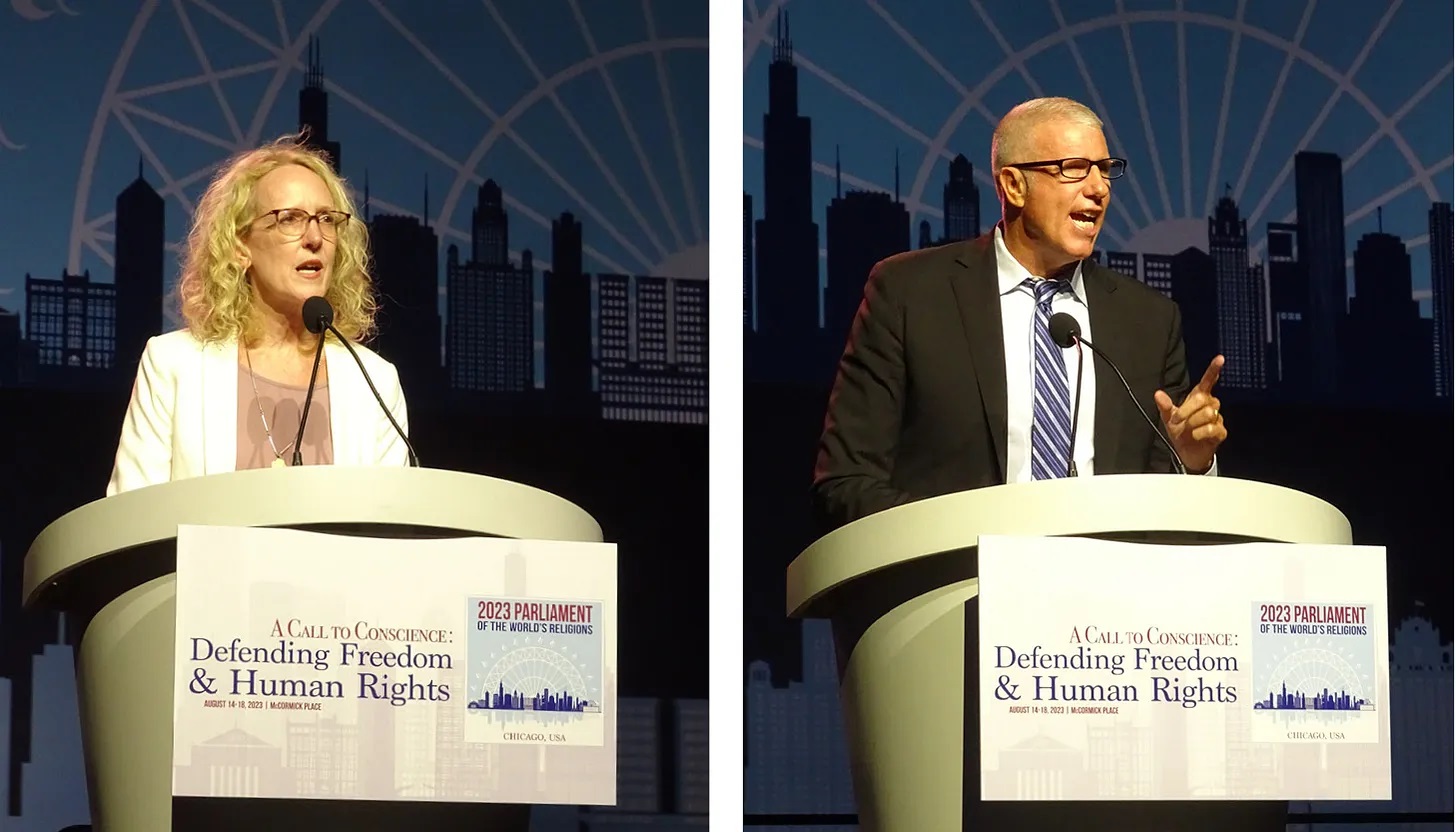

Rev. Rob Sellers, an emeritus professor of theology and missions at Hardin-Simmons University in Texas, posed this question this week during a session at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois. He noted that he is “a lifelong Christian” who grew up Southern Baptist, obtained three degrees from Baptist schools, served as a Baptist missionary in Asia for over two decades, and spent another two decades teaching at a Baptist school. But his experiences in ministry led him to interfaith engagement.

“Interfaith friendship is my calling. Interfaith dialogue is my mission. Interfaith cooperation is my passion,” Sellers said. “For many decades, my life’s journey has brought me into relationships with people who follow other religions and spiritualities. I choose to treat these people with respect, admiration, kindness, curiosity, and compassion.”

“I believe that the best way to relate to persons who follow other faiths is through dialogue and cooperation. Why? Because despite the differences in our religious beliefs, our doctrines, we agree so much on what it means to behave ethically,” added Sellers, who also highlighted “scriptures in my own sacred text, the Bible” that led him to interfaith work.

This attitude inspires the Parliament of the World’s Religions and leads many faith leaders from around the world to participate. The Parliament first convened in 1893 in Chicago in conjunction with a world’s fair. It marked an ambitious effort to create a forum for global dialogue across faith traditions and is often considered the birth of the modern interfaith movement.

For the 100th anniversary of the event, a new Parliament was held in Chicago, which led to an effort to convene such a gathering more frequently to foster intentional interfaith dialogue, understanding, and action. The five in-person Parliaments held in the three decades between that one and this year’s that returned to Chicago included events in Cape Town, Barcelona, Melbourne, Salt Lake City, and Toronto. Sellers served as chair of the Parliament for the Toronto event in 2018.

This year, about 8,000 people from more than 90 nations gathered, representing more than 200 faith traditions (including pretty much every denominational branch of Christianity). The event features plenary sessions, breakout workshops, an eclectic exhibit hall, art installations, and even times to experience religious services like Catholic Mass, silent Quaker worship, Jain meditation, and an Indigenous sacred fire ritual. I presented on a panel about “finding truth in an era of misinformation.”

Left: A banner welcoming attendees to the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way). Right: Mark Wingfield, Mitch Randall, and Brian Kaylor speak on a panel about “finding truth in an era of misinformation” on Aug. 14, 2023. (Missy Randall/Good Faith Media)

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson emphasized the history of the Parliament in the Windy City — and the city’s own religious diversity — as he welcomed attendees. The son of a pastor, he also quoted from Psalm 133 about it being “good and pleasant” when people “dwell together in unity.”

“Your spiritual traditions have the power to guide people to a path of peace and nurture a spirit of mutual respect and collaboration,” Johnson added. “When we think about our mission to promote peace and justice and sustainability and dignity amongst all beings, let’s recognize the urgency of this moment. The urgency of this moment requires us to not just simply rely upon the recitation of scriptures in our sacred books, but it requires us to demonstrate the most incredible act and power known to humankind — and that is the act of love.”

Similarly, Cardinal Blase Cupich of the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago praised the mission of the Parliament “to cultivate harmony among the world’s religions and spiritual community.” But he lamented that “growing silos” created by technological advances have made “dialogue across differences even less likely,” which makes it “easier to vilify and dehumanize” those who are different. Yet, he added, “if we hope to advance the causes of peace and justice in the world, we must continue to seek out more forums like this to connect with one another.”

So this issue of A Public Witness takes you to Chicago to hear a taste of religious leaders calling for the people of the world’s religions to work together for religious freedom and to make a more peaceful and just world.

A variety of religious leaders stand on stage during the opening session of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois, on Aug. 14, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Religious Freedom for All

The theme for this year’s Parliament was “A Call to Conscience: Defending Freedom & Human Rights.” With that theme guiding the sessions and speakers, a key focus this week was the push to ensure religious freedom for all, especially those in minority faiths persecuted around the world simply because of their religious beliefs or lack thereof. The Parliament heard reports of persecution, including about Uyghur Muslims in China, Sikhs in India, and Christians and Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

Modeling the effort to highlight religious freedom at the event, the Parliament included a meeting of the International Religious Freedom Roundtable, which usually convenes in Washington, D.C., to bring together government officials and leaders of religious and other non-governmental organizations to discuss critical issues and find ways to partner together to advocate for international religious freedom. Although the session was open for Parliament attendees, the roundtable events are off-the-record so that individuals can discuss sensitive issues. But other sessions included public calls to work together for the religious rights of all people.

Rashad Hussain, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom in the Biden administration, talked about the importance of fighting for religious freedom around the world. The first Muslim to serve as the U.S.’s religious freedom ambassador, Hussain argued the U.S. is “uniquely situated” to “stand up for human rights and for religious freedom for people everywhere in the world” because of constitutional protections and since “we are also a country that is made up of people from literally every corner of this planet.”

Hussain emphasized that such advocacy is particularly needed today. He argued the Parliament is occurring during an important time when people around the world are “at a crossroad” because “religious freedom is challenged.”

“It’s challenged in so many places around the world, but the growing movement that you all represent is responding. And your movement is growing stronger and stronger, as evidenced by all of you who are gathered here today,” Hussain added. “Now is a critical time. It is not a time for us to be fixated on our differences, but it is a time for us to come together.”

Hussain added this work from his office includes standing up for people who have been “unfairly detained or imprisoned” because of their faith, fighting antisemitism, “standing up against anti-Muslim hatred” like that directed against the Rohingya people in Myanmar and the Uyghur people in China, and advocating to “address discriminatory laws and discriminatory policies, including the use of apostasy laws [and] including the use of blasphemy laws.”

Similarly, Rev. Rob Schenck talked about the importance of religious communities advocating for each other. An evangelical minister, Schenck is starting a new role as a visiting scholar of Christianity and religious leadership at the Miller Center for Interreligious Leadership at Hebrew College, a Jewish school in Massachusetts. He quoted from Stephen Haynes’s book Bonhoeffer for Armchair Theologians to explain Christian ethics: “As Christ lived and died vicariously, his disciples are called to vicarious action and responsible love on behalf of the other.”

“Vicarious action is expressed,” Schenck added, “in concrete Christian advocacy and protection for Muslims who wish to build a mosque, or of Sikhs who have been attacked at their temple, or Jews who have been menaced by neo-Nazis carrying tiki torches. Responsible love is demonstrated in the affirmation of every religious adherent’s human rights, a humble appreciation for what the other may know that the Christian doesn’t know or can’t know, or a celebration of what the Christian and the other share in common.”

Left: U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Rashad Hussain speaks at the Parliament for the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois, on Aug. 14, 2023. Right: Rev. Rob Schenck (second from right) speaks on Aug. 15, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Rabbi David Saperstein, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom during Barack Obama’s second term, also stressed the importance of advocating for religious and human rights. The first Jew to serve as the U.S.’s religious freedom ambassador, he also argued that by working together across religious lines, they can be “the shapers of a better and more hopeful future for all of God’s children.”

“We live in a time when conscience is needed more than ever, at a moment in human history when human rights and democracy and religion and political freedom are under such sustained attack,” he said. “The moral call of the global religious community to stand for freedom and justice and peace is more compelling than ever.”

“We are the first generation that produces enough food to feed every human being on earth. A failure to do it now is a failure of moral vision and political will,” Saperstein added. “We are the first generation that can conquer malaria and an array of diseases that have plagued humanity from time immemorial. A failure to do it now is a failure of moral vision and political will. We are the first generation that can educate every child on earth, lift every person out of poverty, undo the damage to our environment if we act fast enough, spread freedom across the globe. For all of these, our failure to do so at this moment in history is a failure of moral vision and political will.”

But amid the calls for action by the religious communities, many speakers also noted that religion is sometimes part of the problem.

Rabbi David Saperstein speaks at the Parliament for the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois, on Aug. 16, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Threat of Religious Nationalism

While the Parliament brought together people from various faith traditions, some speakers warned that other forces are using religion to divide people. The rise of religious nationalism in various nations stands as a polar opposite to the vision of the Parliament, which is why religious leaders must confront such nationalism in the name of religion.

“Autocrats are weaponizing religion to amass power and maintain control, from Russian Orthodox nationalism to Catholic nationalism in Hungary and Poland to Hindutva in India to Jewish nationalism manifesting in Israel’s new ruling coalition to evangelical and Pentecostal forms of religious nationalism in the U.S. and Brazil,” said Rev. Jen Butler, a Presbyterian minister and author who founded Faith in Public Life. “Religion is being manipulated to give moral sanction to hideous acts of violence that run contrary to moral teachings.”

Butler highlighted how those espousing Christian Nationalism have for years praised Vladimir Putin as a moral leader because of his actions against LGBTQ people and Muslims. She believes these global relationships among those supporting Christian Nationalism magnifies the urgency to speak out.

“It is so critical that we speak boldly from our specific faith traditions to counter the rhetoric of religious nationalists even as we model respect for all faiths,” she explained. “We cannot cede the language of faith to autocrats who perpetuate this outrageous lie that human rights and democracy are antithetical to faith rather than the fulfillment of our religious values.”

“Tyrants will try to convince us that our dream of dignity for all is impossible, unrealistic, or even undesirable,” Butler added. “But hope is born in our ability to imagine God’s vision of human dignity for all becoming a reality. And that is why we’re here in Chicago.”

Rev. Paul Raushenbush, president and CEO of the Interfaith Alliance, similarly warned that “across the world, authoritarian movements are gaining control.” He added, “Too often they are legitimized and sanctified by religious leaders consolidating their own power for their own tradition and restricting the religious, social, and political liberty of those who are different.”

He specifically condemned White Christian Nationalism as “a crusade for power that betrays our nation and degrades my faith.” And Raushenbush criticized the “misuse of the principle of religious freedom” by those pushing Christian Nationalism.

“To which I respond: Who’s religion? And who’s freedom?” he said. “As we are holding this Parliament, Christian Nationalists are attacking churches that do not agree with them. They are attempting to rewrite our history. They are banning our books. They are restricting voting and women’s rights and targeting minority faiths.”

But Raushenbush added that as he looked at those gathered at the Parliament and thought of the faith communities they represented, he saw “the organizational, spiritual, and moral power of religion that the world needs to meet the crisis that we face.” So he urged those gathered to “be guided by love” and to work together.

Rev. Jen Butler (left) and Rev. Paul Raushenbush (right) speak at the Parliament for the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois, on Aug. 15, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Other speakers echoed this call to work together across religions to make the world a better and more peaceful place for all. This included sessions on confronting the climate crisis, addressing nuclear weapons, responding to the Russian war on Ukraine, feeding the hungry around the world, and addressing gun violence. As both Butler and Raushenbush noted, religious nationalism has been fueling and inspiring violence, thus religious leaders at the Parliament considered how to act for peace.

The Parliament also included art installations to help people ponder the crises faced in the world and consider how people of faith could respond. One exhibit featured scraps of orange fabric torn at vigils across the country to represent the more than 30,000 children who have died in the U.S. from gun violence since the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre in 2012. Some of the scraps included handwritten notes and others featured the names of some of those killed.

Next to that display, Shane Claiborne and others from RAWtools brought a blacksmith forge to the Parliament to invite attendees to join them in beating guns into garden tools. As people picked up the hammer and pounded on the hot metal, they created a symbol of what the Parliament hopes to inspire: people coming together across faith traditions to transform the world.

“This is both a form of public lament but also a way of declaring that all things can be made new, that something that’s designed to kill can be recrafted to cultivate life,” Claiborne said as he held up a spade made from a gun barrel. “I tell my evangelical friends: This is what a gun looks like when it gets born again.”

“It is poetic and symbolic and prophetic, but it is also sacramental,” he added. “When we transform that metal, it’s proclaiming that the world doesn’t have to be this way.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor

Left: Shane Claiborne speaks at the Parliament for the World’s Religions in Chicago, Illinois, on Aug. 16, 2023. Right: A man beats on a gun barrel to help transform it into a garden tool. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)