As a Singaporean who has lived overseas for the past decade, coming home for Christmas is always a special time. I love seeing friends and family, basking in the celebratory atmosphere, taking in Christmas decorations, and—as a bonus—enjoying the balmy tropical weather, far warmer than the Christmases I have spent on the North American East Coast, where I am earning my doctorate in anthropology, or in Jordan and the Middle East, where I have worked and conducted research for my dissertation. And, certainly, beyond these little joys, I learned through my faith that Jesus was indeed “the reason for the season”—Christmas marking the birth of Christ, God taking on flesh to reconcile man to Himself, a lowly babe inaugurating a kingdom of peace and righteousness on earth. As Christians, we live in anticipation of this kingdom-not-yet-manifest, in hope of the fulfillment of this promise.

Coming home this Christmas, however, felt different. I had spent the months of October and November glued to my phone, after news first broke of Hamas’ attacks on Israeli citizens on October 7 and then of the Israeli military’s disproportionate response in the weeks thereafter. I watched as horrific violence in Gaza—and later across the rest of the Occupied Palestinian Territories—unfolded over social media through the brave reporting of journalists like Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda and checked in on friends I knew from the region or those who had connections there. Every few days brought new atrocities: Israel bombing a hospital, a Jewish peace activist identified among Israel’s dead, an Israeli airstrike destroying a building in Gaza’s oldest church which had been sheltering those fleeing violence, entire Palestinian bloodlines wiped out under Israeli bombardment. As of this writing, the death toll has reached 22,000, of whom at least 8,000 are children. All this made for a somber Christmas season, culminating with the news that Arab Christian leaders had canceled Christmas festivities in Bethlehem and across the Holy Land.

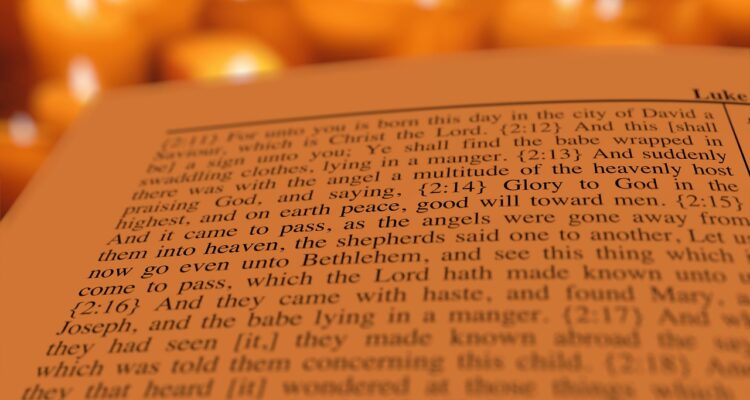

I arrived in Singapore on December 20, and attended a Christmas Eve service a few days later. It was wonderful to see many of my church friends whom I had not seen since my last trip home, and to celebrate this important moment in the liturgical calendar together. I took comfort in the familiar setting, the familiar atmosphere, the familiar music. But when we started singing “o come ye, o come ye to Bethlehem,” the dissonance was jarring. I had been to Bethlehem—three times. I thought of the places I visited there, the friends I made, the people I met, all in mourning during this new chapter of Palestinian Nakba. Did people know that Bethlehem was a real place that still existed? Did they know what was happening in the land in which Jesus lived? Did they know that, if you were to go to Bethlehem today, you would find a church with a doll of baby Jesus, wrapped in a Palestinian kuffiyeh, lying amidst rubble as a commemorative nativity scene? It felt deeply disconnected to be singing and preaching about the good news of Jesus Christ and the liberation He brings with no acknowledgment that, not 50 miles away from His birthplace, there was a literal genocide taking place. Even during the “prayer for the world” segment of the service, there was no mention of the Palestine where Jesus was born, his birth the ostensible point of the entire service.

Two months ago, in Toronto, I attended the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association, the professional organization of my discipline. Anthropologists of the Middle East and our allies organized a series of actions around Palestine: we handed out stickers with the words “Ceasefire Now” and “Stop the Genocide in Gaza” that attendees could put on conference badges; read out the names of thousands of Palestinian children killed in Gaza throughout the duration of the conference; and organized a grief ritual and a die-in inspired by the one held in support of #BlackLivesMatter at our annual meeting in 2014; among other actions. This was the first die-in I had participated in, an experience I found profoundly moving: hundreds of conference attendees lying on the ground, each clutching the name of a Palestinian child who had been killed in Gaza since the start of October. The process took well over an hour and at some point we ran out of space where people could lie down—although we never ran out of names. I thought about this as I was sitting in the pew on Christmas Eve. I consider academics my colleagues but Christians my kin, yet it strikes me that my professional organization was willing to take a stance while so many churches and Christian organizations are not. Certainly, there are exceptions, and I was heartened when my church in Cambridge held a service focusing on Palestine, including the collective reading of a lament written by Palestinian scholar and theologian Lamma Mansour. And certainly there have also been academics who have remained silent on the issue.

When I was growing up in church, the emphasis on the Incarnation always spoke to me: that Jesus was 道成肉身 (“word made flesh”) and 化身之爱 (“love that took on human form”) gives us hope because He understands the human condition in a personal rather than an abstract way. At this moment, what does it mean for us that Jesus was born a Jew, in historic Palestine, during the time of Roman occupation? Growing up, I was also taught that our actions were testament to our faith, that what we did in front of others mattered because others would see the light of Christ in us and glorify our Father in heaven. Now that I’m older, I no longer think that equation is so straightforwardly causal. And, to be clear, I believe there are many ways to help Palestinians. Being vocal about Gaza is just one of them, and is one that in our social media-inundated world can also easily devolve into a kind of clicktivism (even as I note that Palestinians have asked that people keep sharing about what is happening there). Still, I wonder what it means for the testimony of our faith that so many churches are silent about the ongoing genocide in Gaza as it takes place in front of our very eyes, as bombs fall down and corpses pile up in occupied Palestine, where the One we call Messiah was born.

On Christmas Day, Reverend Dr. Munther Isaac preached a sermon from Bethlehem. In his powerful words: “We will be ok. Despite the immense blow we have endured, we will recover. We will rise and stand up again from the midst of destruction, as we have always done as Palestinians . . . for those who are complicit, I feel sorry for you. Will you ever recover from this?” His question should give us pause.

Bio: Timothy Y. Loh is an anthropologist of science and technology completing a doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society (HASTS). He has lived and worked in the Middle East, with stints in Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon, and Palestine/Israel over the last ten years. He sees both his research and his faith as informing an ethical way of being in the world. https://www.timothyyloh.com.