Since our young years of learning how to sense the bloom in a wine and how to cross the line just enough to get a good laugh out of a story, we’ve experienced our own table of shifting seasons. It has been loud and full, surrounded by purposeful blessing over gobs of spaghetti, layers of cake, the pull of monkey bread, the pucker of berry tarts, and, of course, multiple servings of soup or beans from giant pots. We have mastered the art of lining up fold-out tables and making them fancy with cloths and candles. Our years as Anglicans were years of the longest tables, encircled by musicians and singing. I don’t know how many tears fell or how many prayers and goose bumps were raised at that table, how many meetings were held or how many decisions were made. Our table became a place of healing and of untold stories finally given voice. We are Seth and Amber Haines, people of a gathered table.

When we first joined the Anglicans, it was the idea of the communion table that drew me in. I came to believe that an ever-present God was particularly present at the communion table, since he is the host there. He wasn’t literally in the bread, they said, but his mystical presence was conveyed through it, somehow. This is the reason I chose to follow the ordination path. I wanted to be as close as possible to that mystical presence, to that table. That table and what was served there became, to me, the whole thing, the entire reason we met together. I wanted to hold the Eucharist in my hand, my mouth, and my body, even if all I was holding was a metaphor, an idea.

But along the way, the focus shifted, and when the centrifugal force in our community spun so tightly around our leader instead of the communion table, I was catapulted out of orbit. As it turns out, the metaphor of the Eucharist can go only so far when it lives exclusively in the mind or the imagination, when it’s not also lived out in the body.

I wanted to fix our congregation for a long time, but I couldn’t metaphor my way out of our confusion. When despair set into my ministry, I wanted to be fixed, to be safe and fed, but I couldn’t think of a single thing to heal me: not the table where the priest offered communion to me; not the table of my friends who wanted to preserve the church at the cost of my story; not even my own table, a table where our church used to gather for meals and music and laughter.

Our identities are tied to what and who feeds us. We are, in fact, what we eat. So what happens when we don’t have a safe table? What happens when we stop eating altogether?

The memory of my inability to see God’s love is strangely vivid for someone who was so far under the river of grief that she was blind. I remember not seeing God’s love, not tasting it at the eucharistic table. The table where I’d once found so much life was no longer safe, because what was supposed to be nourishing was overshadowed by something else. So there was no bread to hold, and in the absence of bread, I groped around for something to stop the hunger pangs.

Now, here’s a hard thing to confess. I don’t want to write this, but I understand reaching for a gun. I understand reaching for another lover, a bottle, anything. How do you stop hunger when there’s no food that can satisfy you? How do you keep that hunger from driving you crazy?

There was a season after the fall-apart when nothing felt safe or sane. When I left the house, I shook violently. I became obsessively afraid that I would stop my car in the middle of any four-way stop and cause a crash from every direction. Driving through a stoplight has been one of the bravest things I’ve done in my life, and no one knew it. There were days I didn’t get in the car unless I had to, because it took so much energy to act like I was okay in front of the boys and to make it back home alive.

It’s hard to explain, but in those days, I could hold our children, remember exquisite meals, see the food in the refrigerator, and reach over in the night and know Seth was beside me, but none of it felt safe. If the Eucharist table could be robbed of safety and meaning, why couldn’t any of these other things? Finding God in all things is easier said than done when you’re in the middle of despair. How do you move forward when even the good things, the gifts, feel like loss?

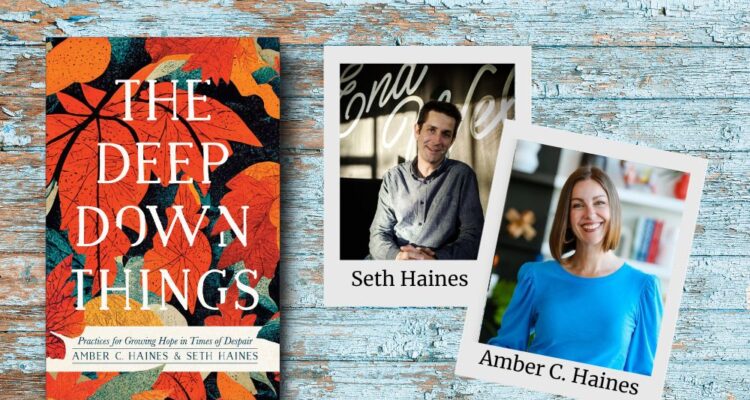

Content taken from The Deep Down Things by Amber C. Haines and Seth Haines, ©2023. Used by permission of Brazos Press.

Amber C. Haines is the author of Wild in the Hollow: On Chasing Desire and Finding the Broken Way Home and The Mother Letters. Seth Haines is the author of Coming Clean (winner of a Christianity Today Book Award of Merit) and The Book of Waking Up. Together with Tsh Oxenreider, he cohosts the podcast A Drink with a Friend. Amber and Seth have experience speaking at conferences and events. They live in Fayetteville, Arkansas, with their four boys.