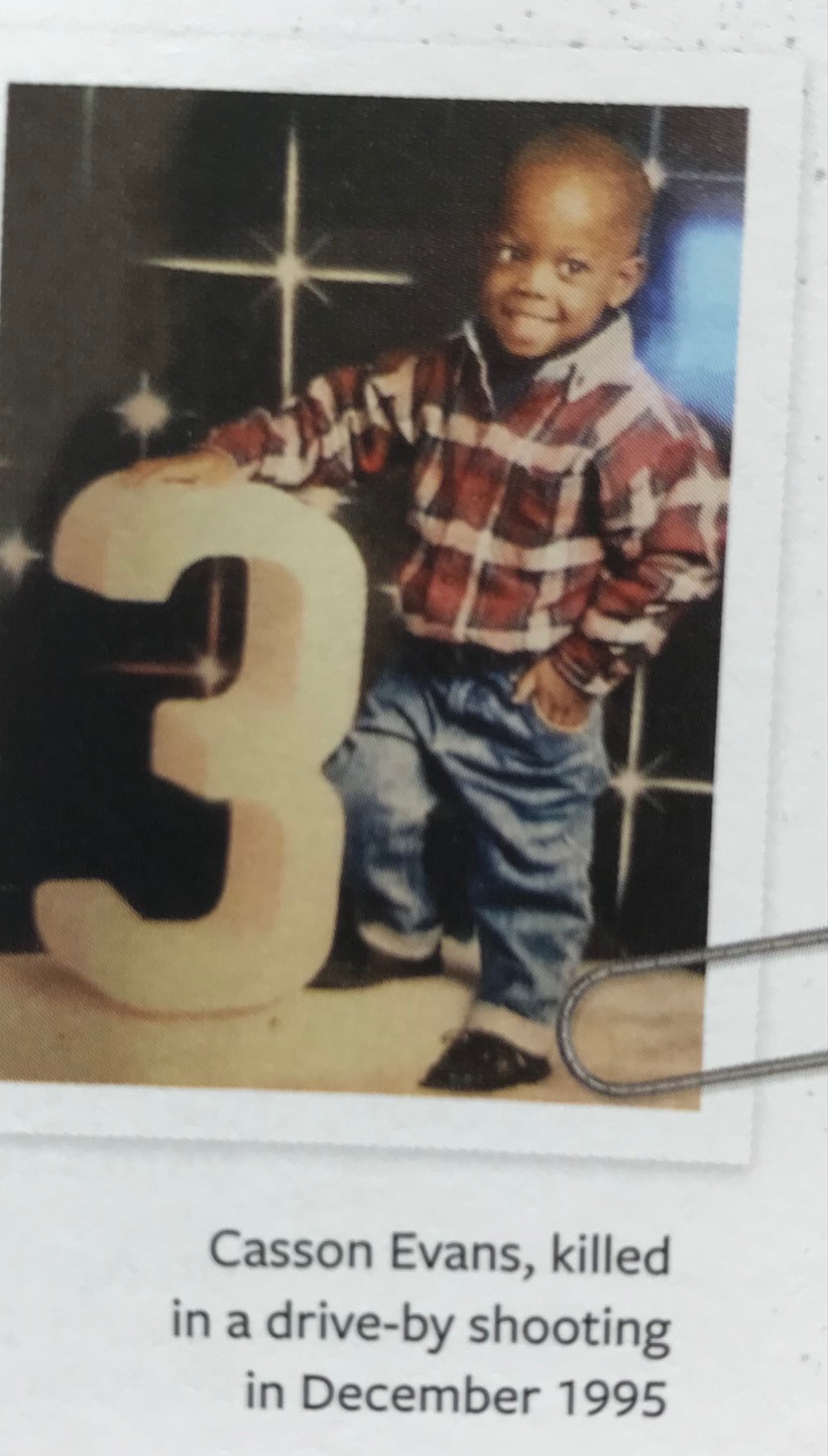

It was the winter of 1995, just before Christmas. Sharletta Evans had her two sons with her as she drove to a relative’s house to pick up a grandniece after a drive-by shooting in their neighborhood the previous night. She left the kids in the car with her twenty-one-year-old cousin and seventeen-year-old niece and went inside to pick up her grandniece. While she was inside, the shooters came back. Bullets rained down on the car and the house. After the shooters left, Sharletta went back out to the car to find that the bullets missed her six-year-old son, Calvin, but one hit her three-year-old son, Casson, in the head.

Sharletta held her son and walked on the sidewalk. She talked to him. “You can make it. Hold on big guy.” Her dress was covered in blood from her collar to the hem. As the ambulance arrived, Casson took his last breath in his mom’s arms. Attempts to revive him at the hospital were unsuccessful.

What happened next Sharletta can only describe as an act of God. She heard a voice asking her if she would forgive the people who did this. By the power of the Spirit, Sharletta said she forgave them.

Seventeen years later she would be the first person to participate in a pilot program with the Colorado Department of Justice, the High Risk/Impact Victim Offender Dialogue. The victim-based restorative-justice program makes it possible for victims to meet with their offenders. There’s a long process of counseling on both sides that prepares the victim and the offender to explore every possible outcome from such a unique and weighted conversation.

Raymond Johnson was one of three teenagers in the drive-by car, and it was determined that he was the one who fired the bullet that killed Casson. At the time in Colorado, juveniles could be sentenced to life without an opportunity for parole, as Johnson was. As reporters explained about the program, “Beyond a sheer willingness to participate in restorative justice, the offender has to meet a three-part test for acceptance based on demonstrating accountability, genuine remorse and willingness to repair harm. Johnson met all the criteria, though on the last count the only reparations he could offer were honest answers to a mother’s unanswered questions.”

“There were so many questions,” Sharletta said. “When it came to every emotion, [my facilitator would] ask me where was I at. What did I want to say to him? I really had to dissect every emotion so there were no surprises.”

After each of them had prepared for their meeting, Sharletta and Raymond spent time asking each other questions and recalling that night seventeen years prior. Since their meeting, the Colorado Supreme Court struck down life sentences without parole for juveniles, and Sharletta has actively testified for Raymond to get a new sentence with an opportunity for parole. Sharletta actively advocates for victim-offender dialogue and juvenile sentencing reform. She has testified numerous times for restoration.

In 2009, three years prior to their meeting, Raymond sent Sharletta a Mother’s Day card and asked if she would be his mother. She didn’t answer until their meeting. It was hard for her to consider. Their meeting lasted eight hours. At the end, she held his hands and prayed over him. She also brought the card he sent and told him, “Yes, I will be your mother.”

In 2016 Sharletta was able to meet with the driver of the car through restorative justice.

Sharletta’s story of forgiveness and extensive work to offer the opportunity for restitution and restoration for offenders is awe-inspiring. It’s an example of what it looks like to no longer learn how to make war. It’s what we’re called to do when we choose to carry a plow instead of a gun. We have to recognize the trauma in our community and support the people like Sharletta who are working so hard, telling us to see the face of God in others.