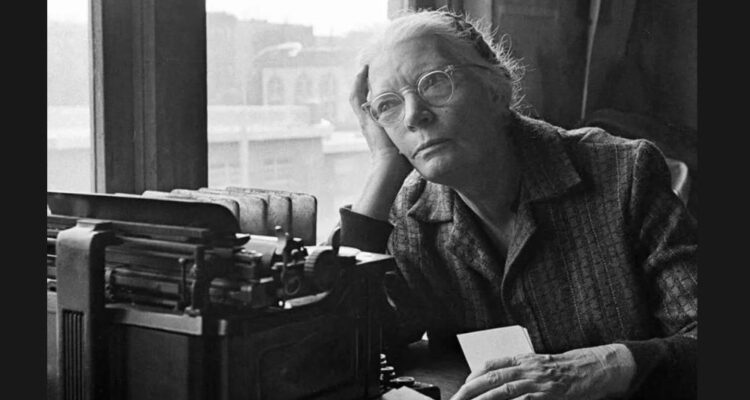

Dorothy Day’s article, “Suicide or Sacrifice”, was previously published by The Catholic Worker on November 1, 1965 and is reprinted with permission.

On November 9, 1965 Roger LaPorte, a young man who had been volunteering part-time at the Catholic Worker, immolated himself on the steps of the United Nations as a protest against the Vietnam War. He died the next day. No one at the Catholic Worker had known of his intentions. Nevertheless, Dorothy was blamed by many—even by some of her supporters–for encouraging this “suicide.” In her reflections, Dorothy acknowledged the church’s prohibition of suicide, but preferred to see Roger as a “victim soul,” who had taken on the suffering of others in hopes of easing their pain. (On Pilgrimage: The Sixties, by Dorothy Day and Robert Ellsberg, editor, published by Orbis Books)

Dorothy concluded by reflecting on the significance of intentions, noting the importance of purifying one’s intentions, “and how complex and elusive a thing an intention is and how often other motives of which we are unaware are at work. Finally: “There will undoubtedly be much discussion and condemnation of this sad and terrible act, but all of us around the Catholic Worker know that Roger’s intent was to love God and to love his brother. May perpetual light shine upon him and may he rest in peace.”

Suicide or Sacrifice?

by Dorothy Day, November 1, 1965

Summary: Reflects on the self-immolation of Roger LaPorte as a protest against the Vietnam war. Discusses suicide doctrinally, psychologically, and in literature. Tries to understand his intentions and the need for protest in the midst of war and building for war. Speaks of the notion of the victim soul and why she prays for those who kill themselves. (DDLW #834). The Catholic Worker, November 1965, 1, 7.

A Carmelite priest was called to the Emergency Ward of Bellevue Hospital last month where Roger LaPorte lay dying of his self-inflicted burns which covered ninety-five per-cent of his body. According to the testimony of the priest, Roger having made his confession, made an act of contrition in a loud clear voice. Unless we wish to doubt the integrity of a dying man, we must believe that he knew and realized with the clarity of one who lay dying, that he was wrong in taking his own life, trying to immolate himself, to give his life for the cause of peace. He had said he wanted to “end the war in Vietnam.”

He wanted to lay down his life for his brothers, to take his own life instead of taking theirs, to follow the example of the Buddhist monks, and the two other Americans, who had done the same.

It has always been the teaching of the Catholic Church that suicide is sin, but that mercy and loving-kindness dictated another judgement: that anyone who took his life was temporarily unbalanced, not in full possession of his faculties, even to be judged temporarily insane, and so absolved of guilt. Many years ago, when the eighteen-year-old son of a friend of ours committed suicide, a priest told me: “There is no time with God, and all the prayers you will say in the future for this unhappy boy will have meant that God gave him the choice at the moment of death, to choose light instead of darkness, good, not evil, indeed the Supreme Good.” I had been a Catholic only a year, and I had the names of ten people I knew who had taken their own lives on my prayer list. As I look back, I recall how many of my own dear dead never had in this life a living faith.

November is the month when the Church commemorates all the holy ones who have ever lived, on All Saints’ Day. To be holy is to be whole. On November 2nd, she commemorates all the souls who have gone before us. So it is fitting to be writing about these things now.

I remember how Kirilov, in Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, took his own life, in this case as his supreme denial of the existence of God, to demonstrate to the world his conviction that man is not created, that his life is his own and he can lay it down as he pleases. Kirilov is the supreme literary example of self-will and self-deification.

I remember also reading in the memoirs of Lenin’s widow her account of the self-inflicted deaths of Karl Marx’s daughter and her husband, and her own commendation of this act. They had finished their work; they were making the supreme assertion of man’s autonomy. They died as they had lived, she wrote, consistent with their principles.

I mention these two instances of suicide on the part of those who were dedicated to serve their brothers and who had lived for what they considered truth in themselves and in the world. Perhaps the current reaching out for dialogue between atheist humanists and Christian humanists (see January 1965 Catholic Worker) will explore this field more deeply.

But the case of Roger La Porte was different and must be spoken of and written of in a far deeper context. It is not only that many youths and students throughout the country are deeply sensitive to the sufferings of the world. They have a keen sense that they must be responsible and make a profession of their faith that things do not have to go on as they always have–that men are capable of laying down their lives for others, taking a stand, even when the all-encroaching State and indeed all the world are against them.

In Ignazio Silone’s book Bread and Wine, the revolutionary in hiding risks capture by going out and chalking slogans on the walls of the village where he has taken refuge, and when he is scoffed at for the seeming futility of this gesture, he answers:

“The Land of Propaganda is built on unanimity. If one man says, ‘No,’ the spell is broken, and public order is endangered.”

Throughout our country the protests against the war in Vietnam have grown and young men have been imprisoned, some of them for years. (One was recently sentenced to five years for refusal to cooperate with the draft.) Stories keep coming out in the press of planes spraying napalm, gasoline jelly, over the enemy, and that means over villages of men, women and children; of mistaking targets and destroying innocent villagers. In forty-eight hours, last week, there were six massive air strikes. There were more killed on both sides last week than at any time since the war began. The Wall Street Journal for November 3rd had a first page, first-column headline.

“Vietnam Spurs Planning for Big Rise in Outlays for Military Hardware. Spending on Tanks, Copters, other Gear may double…

“‘Now that we are finally committed to an active combat role in Vietnam the whole atmosphere has changed within the Pentagon and elsewhere in Government,’ says one Defense official. Extra Zip for Economy … Both the Army’s spending plans and those of the other services promise added zip for the nation’s peppy economy… added billions will be funneled into pocketbooks in many parts of the land.” The story goes on with “shopping lists” and paragraph after paragraph listing the expenditures to be made for this “five-year package” as it is blithely called. There is something satanic about this kind of writing, which envisions a colossal waste of the resources of the earth, and of man himself.

One day our Catholic Worker farmer, John Filliger, talking of drying up the cow a few months before she was about to calve, said, “The only way to do it with a good cow like this is to milk her out on the ground. She gets so mad at the waste of her milk that she dries right up.” That may be an old wives tale, or an old farmer’s tale, but there is a lesson in it. We waste what we have, and the source of supply will dry up. Already we are suffering a drought in the whole Northeast. Any long-range viewpoints to an exhaustion of our economy, not to speak of man himself.

On the other hand, witness Roger La Porte. He embraced voluntary poverty and came to help the Catholic Worker because he did not wish to profit in this booming economy that The Wall Street Journal speaks of so gloatingly.

Many a time when I have spoken in colleges, the bitter comment is made that “conscientious objectors should not benefit by the high standard of living made possible by our American way of life that our boys are fighting for.”

Conscientious objectors around the Catholic Worker certainly do not so benefit. In the Second World War those who accepted alternative service in hospitals and camps around the country worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week, in order to save up four days a month to take a brief leave. They not only had no pay, but some of the religious peace groups stipulated that they pay their own way, thirty-five dollars a month, to show their willingness to go a “second mile” with the Administration. I am glad to see the stiffening of resistance to war and conscription in this present war.

Roger La Porte was giving himself to the poor and the destitute, serving tables, serving the sick, as St. Ignatius of Loyola did when he laid down his arms and gave up worldly combat. Roger wanted to continue working to support himself, and he was looking for an apartment so that he could take in others and by living poor afford to help others more.

And now he is dead – dead by his own hand, everyone will say, a suicide. But after all, there is tradition in the Church of what are called “victim souls.” I myself knew several of them and would not speak of them now if it were not for the fact that I want to try to make others understand what Roger must have been thinking of when he set fire to himself in front of the United Nations early Tuesday morning. There had been the self-immolation of the Buddhist monks; and of a woman in Detroit, of a Quaker in Washington – all trying to show their willingness to give their lives for others, to endure the sufferings that we as a nation were inflicting upon a small country and its people by our scorched-earth policy, by our flamethrowers, our napalm. One priest we knew in the Midwest offered his life for his parish and when he said this, he spoke of some child suicides, whether in his own or a neighboring parish I do not know. He offered his life, and God took him a year later. He died after a six months’ illness with tumor on the brain. Another priest was stricken with paralysis and dies daily in a long illness. Our own Father Pacifique Roy, whom I visited when he was confined to a hospital in Montreal, said, “We say many things we do not mean to God and He takes us at our word. You make an offering. He accepts it. But he always gives strength to accept the suffering.” All these priests knew that only in the Cross is there redemption.

We have this teaching in the Church about victim souls, but what about that teaching of an eminent theologian, quoted in many a diocesan paper and religious weekly last spring, who said that it was permissible for a man in the service of his country to commit suicide if he was in danger of betraying secrets of his country to the enemy? (If I can find this quotation by the time this paper goes to press, I will reprint it.)

I have heard it said that in the armed services of some countries suicide pills were given to soldiers to take if they were in danger of torture when captured. Certainly Andre Malraux, in Man’s Fate, told of this and he also said that once a man had taken the life of another, all was changed for him in his life, that he had crossed a certain point and would never really recover from the effects, no matter how hidden.

Last week, on the occasion of a college talk, I was the guest of a priest who had been a chaplain in the Army, who told me that he would use any weapon if he were about to be attacked, gun or bayonet, but he added that he had encountered many soldiers who refused to use their arms, who would accept death, rather than inflict it. According to an article on Suicide in The Catholic Encyclopedia, such an action might come under the heading of suicide, as being a direct refusal to save one’s life.

In this month’s Theology Digest, Father Karl Rahner, S.J., has an article called “Good Intention.” Roger “intended” to lay down his life for his brother in war-torn Vietnam. The article is about purifying one’s intention and how complex and elusive a thing an intention is and how often other motives of which we are unaware are at work. There will undoubtedly be much discussion and condemnation of this sad and terrible act, but all of us around The Catholic Worker know that Roger’s intent was to love God and to love his brother.

May perpetual light shine upon him and may he rest in peace.