“Heal my heart and make it cleanOpen up my eyes to the things unseenShow me how to love like you have loved me.Break my heart for what breaks yoursEverything I am for your Kingdom’s cause

As I walk from earth to eternity.”

Last weekend my wife, Missy, my 8-year-old son, Silas, and I went to the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis which is the site of the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This was the first visit for Silas. Given the color of my skin and the fact that I have been blessed to obtain a higher level of education, and therefore a higher level of income, I have had the privilege and opportunity to largely shelter him from some of the harsh realities of the world and to be the one to introduce him to them and interpret them to him. That is simply not possible for many people and it is a privilege that I believe comes with a great sense of responsibility.

I don’t want him to grow up and be in denial that there are injustices, inequalities, and other major issues in the world though they are right before our eyes. I don’t want him to be blinded to the pain of others due to a high level of personal comfort, a lack of being affected personally, or because he has assimilated to a political, social, or philosophical paradigm. I don’t want him to be afraid to follow his convictions and therefore shrink in the face of pressure, bullying, or fear of exclusion by peers. I don’t want him to grow up to react to the acknowledgement that black lives matter with the rebuttal that all lives matter. I don’t want him to grow up to ask “What about black on black crime?” and to not really want to explore the deeper meaning of, and answers to, that question.

When we looked at the conditions on the slave ships and the treatment that the enslaved endured he was dumbfounded. “How could people do this?” I could answer that the personal and collective psychology of the perpetrators was one of denial that these captured humans were fully human and had worth. Their lives did not matter. The consensus was that a superior race can do this to an inferior race.

When he saw visual representations of babies being taken from their mother’s breast and separated from them for life we were all three visibly upset. He positioned himself between us and held onto us. So we huddled up and talked about it: “What if that was us? Even under the best circumstances, do you think that trauma would find full healing in our bloodline by the time our great grandchildren got here?” When he’s older I will ask, “Do you think developmental traumas, attachment disorders, the mental illness that comes with such comprehensive suffering, the internalized hatred towards self, and the justified but unexpressed rage that gets stuck in the psyche and the body can find resolution in a hostile or indifferent world?” “Do you see how not just an individual, but also an institution or a society, can suffer from collective narcissism, projection, and denial?”

At one point Missy looked at me with tears in her big, beautiful eyes and said “We’ve got to do more.” I fell in love all over again.

When we got to the exhibit about Ole Miss and James Meredith it became more real for him. He loves Ole Miss football. His mother and I both teach at Ole Miss. In this exhibit there was footage of Mr. Meredith’s three denials for enrollment as well as footage of Governor Ross Barnett coming up from Jackson to “personally deny Mr. Meredith admission in order to preserve the integrity of the institution” with a hateful smirk and haughty, superior, unloving tone in his voice. This got to Silas. He recognized the setting. He saw the streets, houses, buildings, trees that are still here. It became real for him. After the video, he took a minute to make sure he could maintain his composure before going to the next exhibit.

Then we saw the KKK costume. He had lots of questions. His mom told him that when I was younger I was arrested for protesting them. He looked at me and grinned. A seed was planted.

There is a bus in the museum with a statue of Rosa Parks sitting in her rightful place. He wanted a picture with her. He sat behind her and put his hand on her shoulder in a loving way. He exhibited a softness and a desire to be affectionate toward her. If she had been a live person, he would have embraced her.

All of this is so foreign to him. His heroes have so far been African American. When he was four he became fascinated with Neil deGrasse Tyson through watching documentaries. He wrote him letters and begged us to take him to the planetarium that he heads and asked for him when we got there. His sports hero is Paul George. He has a Paul George shower curtain. He’s written him letters as well. In those letters he is thanking them for inspiring him and affirming the value that these men carry for him. That love is pure. That is why I try to preserve his innocence and try to interpret the world to him.

Racism is not innate. It is taught. It is learned. And it is traumatic to the psyche of the hated and the hater alike. It is a spiritual cancer. A social cancer. A crippling disease. A destroyer of innocence. It is evil. It is not God’s way.

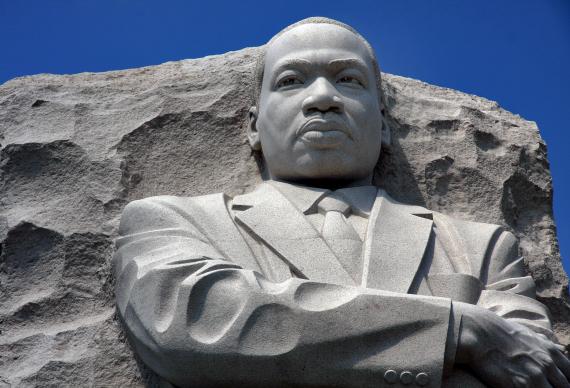

When we got to the end of the exhibit we saw rooms 306 and 307 and the balcony outside of these rooms. From that view you can see where Dr. King was standing when murdered and where the bullet came from. That is where the above picture was taken. The markers in this area contain an account of how Dr. King was nervous and could not sleep that night before he was shot. He was afraid. Larger forces in the world wanted him dead. He knew that many carried something in their hearts even more dangerous than disinterest toward him.

At this spot was the following quote from his father, Martin Luther King, Sr.: “We had waited, agonizing through the nights and days without sleep, startled by nearly any sound, unable to eat, simply staring at our meals. Suddenly, in a few seconds of radio time it was over. My first son, whose birth had brought me so much joy that I jumped up in the hall outside the room where he was born and touched the ceiling — the child, the scholar, the preacher, the boy singing and smiling, the son — ALL OF IT WAS GONE.”

As I’m simultaneously looking at my son sitting in this spot looking at where another man’s son was murdered and reading this father’s words about losing his son in such a horrific way, I recaptured the appropriate kind of heartbreak that I hope to carry all of my days. It is a sacred heartbreak. And to see my son feel it as well is so affirming that his heart which loves God so much also loves God’s people appropriately and, therefore, he can be broken over what breaks God’s heart.

On the way home Missy said, “Silas, I want to know how you are processing all of this.” He replied, “That stuff back there, that’s terrorism.” My heart smiled. He got it. Mission accomplished.

The next morning I preached a sermon tying the Beatitudes and a Christian response to social justice issues together. When it was over and I sat down, Silas curled up to me and wrapped his arms around me. He is precious. He is God’s. Just like every boy and girl on this planet.

I’m often discouraged. I’ve often wondered why we are here in Mississippi and how our call to serve God’s purposes in this world can be expressed during our lifetimes in this place, especially as that expression, that call, has called us deeper into the discomfort of figuring out how to relate to a broken, hurting world in ways that are consistent with our faith. But toward the end of the museum, I recognized it in the words of Dr. King: “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, to Georgia, to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities…..knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.”

For better or worse, this is definitely a part of our call. That is why we happen to be blessed to teach at Ole Miss, with it’s troubled history and lingering problems, of all places. This is why we happen to be blessed to teach classes on social issues, social justice, and how to understand, to look deeper, how to engage, and how to create change. This is why we are blessed to be part of a passionate and diverse faculty that is making a difference in the world. This is why we are blessed to spend time in a counseling capacity with people affected by the social ills of our time and place and whose need for a safe place qualifies them as “the least of these.” And every time a student finds their voice in class, every time a student crosses that stage at commencement, or a client gets ready for discharge, I see empowerment, I see change, I see human flourishing, I see the overcoming of obstacles, I get a glimpse of God’s dream for the world, God’s handiwork in action in real time, and I know that I am a blessed man to be able to observe it all.

In each class yesterday we, Black, Hispanic, and White together, spent a lot of time in conversation, checking in with one another, and talking about how we are all processing everything, supporting one another, honoring one another’s viewpoints, and sometimes peacefully agreeing to disagree. And we will take that heart into our homes, communities, jobs, and places of worship. I am blessed to be able to engage in such beautiful dialogue with such beautiful souls.

Taking a stance is not easy. It’s scary. It’s stressful. It’s exhausting. You lose friends and gain enemies. It’s harder to relax. It’s burdensome. It’s lonely. But it’s part of the work that God has given us. We are blessed beyond measure. And “We’ve got to do more” means “We have more to do.”

I believe in the God that brings about the reconciliation of all things and the healing of the world. I believe that God has a dream for the world that is yet unfulfilled, and I can think of no other way I’d rather spend my days than participating in the coming of that Kingdom, that Beloved Community, in some small way.