One Coin Found was not written for me, but I needed to read it anyway.

Although I also grew up in one of those relatively liberal Protestant denominations, spent some limited time co-mingling with evangelicals because of their fervor, and attended a Lutheran college, I did none of those things while carrying the identity of an LGBTQ person. Author Emmy Kegler admitted on Twitter what she unwittingly discovered at her book launch event: This faith memoir is really for her 17-year-old self.

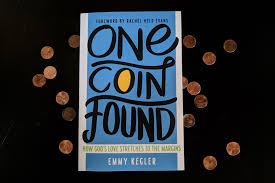

One Coin Found: How God’s Love Stretches to the Margins is full of longing, a desire to embrace and be embraced by God and the Church — all through the witness of faithful people like those found in the Bible. For young adults searching out their footing as queer people of faith, it could serve as both a road map and a tangible sign of solidarity.

Rev. Emmy Kegler loves Jesus and church and words. She also loves women. All of these loves are abundantly apparent in the way she uses her words: Kegler coins evocative phrases like “a spiritual allergy to the word ‘sin.’ She debunks some of the common LGBTQ “clobber verses” in the Bible. She distinguishes between “real” and “true” — although I think I have usually understood those terms in the opposite way from how she describes them in Chapter 1. Kegler shows her relief at identifying with the suffering of Christ, because although it is horrific, it is the experience of a marginalized person revealing who they really are.

At the same time that she identifies with Christ, Kegler admits that her story is not as traumatic as members of her LGBTQ family like Matthew Shepard, who was killed the year before she realized she was gay. Her privilege is apparent in thinking that people who hated and wanted to hurt LGBTQ folx did not even live where she lived. It is perhaps a slower read at points because of her safety — not that a reader would wish any added oppression — as she struggles primarily with this one trait among the intersectional oppressions faced by others in the LGBTQ community, including economic instability, alienation from family support systems, and marginalization of people of color. On the other hand, maybe this is what makes it more accessible to those from a similar white, middle-class, suburban background.

For the faithful who really like to get into theology, Kegler picks apart why different approaches to interpreting homosexuality in scripture ultimately left her unsatisfied, landing on the most pithy and meaningful theology of the entire book: “a hermeneutic of the hip” from the story of Jacob who wrestles with God until God blesses him and leaves the encounter limping.

This must be the hallmark of a truly worthwhile memoir: I am not the intended audience, yet I still found it insightful and applicable, not only as a “window into her world” but in my own faith journey.

Emmy Kegler’s hard-won love of scripture is such a struggle because of us. We, who do not include ourselves in the circle of her queer family members for whom this memoir is written, need this book to tell the truth about ourselves. She writes: “The brutality of others’ silence and apathy is a test to my faith far more than my mental illness has ever been.”

Readers cannot escape how depression and anxiety are intertwined with Kegler’s identity throughout. There is a much higher suicide rate among teens and young adults who identify as LGBTQ, but there is nothing like a meticulous personal description of the effects of mental illness and social triggers over time to put flesh on those statistics. One Coin Found repeatedly emphasizes how differently scripture sounds in the ears of those who have been pushed to the margins.

I will admit I appreciated reading and having the type of church I belong to characterized in this way:

This was the danger and blessing of my liberal mainline upbringing: I was not raised to be afraid of God. I was not taught to be too scared to question. All of my models for living, from my mother to my storybook heroines to the faithful women of the Scriptures, told the same story: we are a people who push back.

Maybe you find yourself in a progressive faith community now and this makes you feel a little smug as well. But that smugness must confront the reality that however accessible our theology, many people like Kegler are drawn to join worshiping communities like the evangelical one that would ultimately condemn her sexuality, primarily because of the lack of enthusiasm for faith and spiritual life among their peers in the congregations of their upbringing.

Even if we do not readily identify with the lost coin, the lost sheep, or the lost sons on different sides of the door to home, we are beloved by a God who will put down everything to search for the ones whom we have pushed to the margins. That tells me something significant about who I am, too.