“Fred, ” I ask in Creole last Friday in Port-au-Prince, “do you mind giving us a quick campus tour before we sit to talk?”

I work with a non-profit focused on education in Haiti, and Fred is one of 25 Haitian seminary students we give full scholarships to and who intern with us. I was about to introduce the students to our board of directors.

“Yes, no problem.”

“Thanks, Fred. And how are you?”

“Good. You and your family?”

“They’re well, thanks. And your family?”

Fred pauses. He’s in his mid-20s. His charismatic spark usually shadows his slight frame, but I’m realizing it’s not lit today.

“I’m OK, ” he says. “But, well, my younger brother was murdered last night. I found out this morning.”

What can you say?

Nothing, of course.

What can you say?

Ask. Feel your heart break a little next to his. Find out his brother’s name was Macdonald. That he was fifteen. That they were robbers who killed him in the sometimes-unsafe neighborhood where their family lives. That on days when Fred couldn’t get home because of his studies, his mom would send Macdonald up with dinner for him.

Fred then stands in front of our group to graciously welcome us to his campus. (After he told me the news, we talked and then I suggested someone else do it. But he wanted to.) Alongside studies, these students engage in the hard, complicated work of helping churches to improve their education and to take more responsibility to protect vulnerable, exploited children in their communities.

Seminary is a time to learn about big “What can you say?” type questions, which are searingly unacademic for Fred right now. Practice and theory should crash into each other. Just not so violently.

Fifteen years ago, I was a second-year seminary student. I studied in Princeton, which is about as far from Fred’s reality as imaginable. I’m grateful seminary helped aim the trajectory of my thinking, my faith and the work I do. He and the other Micah Scholars are promising leaders who wanted to go to seminary but didn’t have the means. They deserve the chance too; good both for them and their communities. It’s an honor to be part of doing this for Fred. But there’s something more. I’m humbled to get to do this work and this searching about God and life with him.

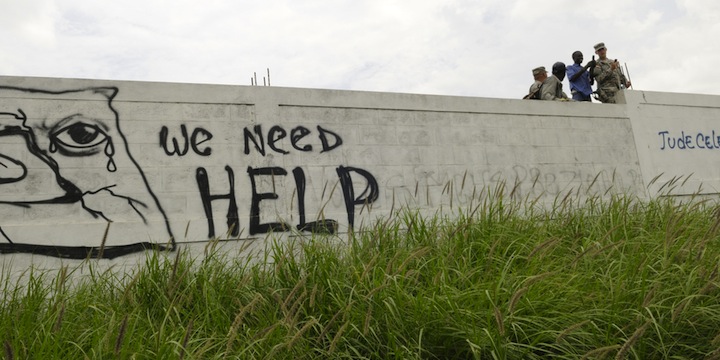

Early Sunday morning, two days later, I attend Fred’s church with some of my visiting friends. The church was gray unfinished concrete all around, floor, walls, ceiling. The orange and red plastic flowers in front of the pulpit were slightly wilted. The singing and worship was anything but. Gospel-type hymn singing was drenched in holy sweat and pushing the speakers to wattage-crackling limits. Faith achieved lift-off from the rough floor on the spirited songs and prayers of hundreds of voices squeezed close on wood benches.

The pastor preached (again, speakers crackling) about tragedy — the earthquake, the death of Fred’s brother — and about the kind of faith that doesn’t crumble. They took an offering and many people who have very little walked to the front to put coins and crumpled bills in a wooden box to help Fred’s family. After helping with funeral logistics, Fred had arrived late at church to teach Sunday school.

The service ended. We said goodbye and hugged Fred in another of those moments when silence, speaking and actions need to find a way to rhyme:

To tell him we care about him and that we’ll pray for him … but not to pretend that’s enough.

To stand with him in faith … but not say “It’s all in God’s plan” or some such theological opiate.

To not let the pain and mystery cower us into silence … about the hope we still somehow hold.

To do something real to keep helping. Because if we don’t, any theology and comforting words rightly collapse. But if we do, hopefully we take another step together toward love and truth.

—

Kent Annan is author of the new book After Shock: Searching for Honest Faith When Your World is Shaken. He is co-director of Haiti Partners and also author of Following Jesus through the Eye of the Needle. (100% of the author proceeds from both books go to education in Haiti.)