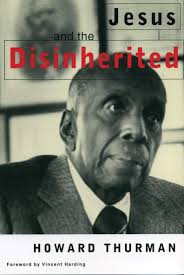

In his timeless book “Jesus and the Disinherited,” Black minister and theologian Howard Thurman wrote, “There is one overmastering problem that the socially and politically disinherited always face: Under what terms is survival possible?”

This was not an abstract question for Thurman.

During the Great Depression, he observed already impoverished Black people further crushed by the nation’s worst economic crisis. He saw the political gamesmanship that made the New Deal into a “raw deal” for Black citizens.

During World War II, he noticed the Black women and men who supported America’s war efforts found their service rewarded with racism and discrimination when the war was done.

His experience during the Depression and the war fueled his writing, especially his 1935 essay, “Good News for the Underprivileged,” which he later turned into a book published in 1949.

The issues Black people and other marginalized groups face today are not all that different from when Howard was writing.

Women still do not get equal pay for equal work. Black unemployment has decreased but still remains about twice that of whites. And Americans who are rich and guilty fare better in the criminal justice system than those who are poor and innocent.

Where is the good news in this situation?

Of course, Jesus is good news for the disinherited. But we also might ask, “Can Christians practice politics in a way that is also good news for the disinherited?”

After all, politics have played a role in creating the rampant inequality in our nation. And politics will have to play a role in addressing this issue.

But followers of Jesus have very different views on politics these days and often find themselves at odds with one another.

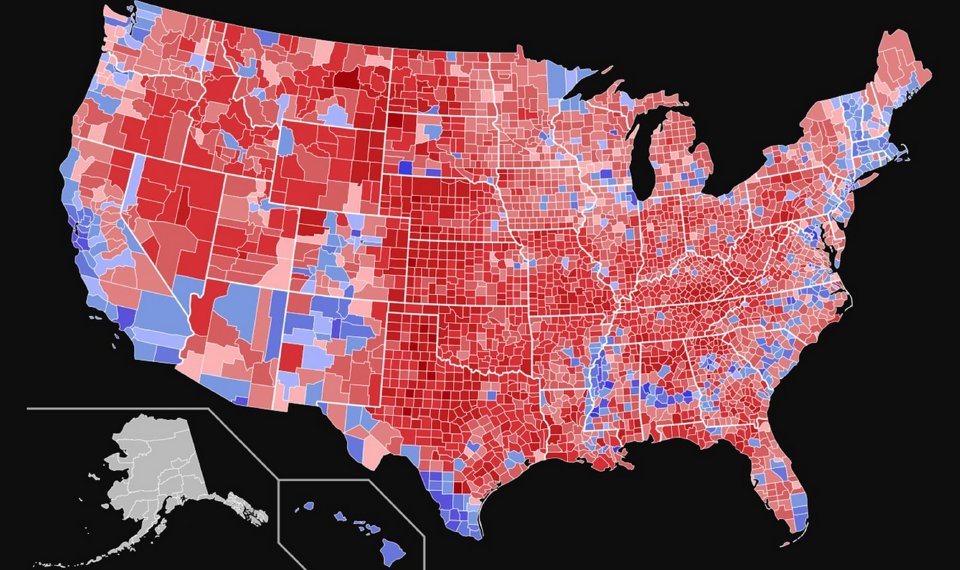

White evangelicals, for example, remain among President Trump’s most loyal supporters. Among white evangelicals who voted in the 2016 presidential election, 81 percent pulled the lever for Trump.

By contrast, more than 6 in 10 evangelicals of other races and ethnicities preferred Clinton leading up to the election. And a recent study by Lifeway Research of Protestant pastors found that just 4 percent of African-American pastors approve of the president’s job performance so far, while more than half, 54 percent, of white pastors approve.

What could possibly bridge this political divide?

I would suggest starting by putting ourselves in the shoes of those Thurman describes as the “disinherited.”

“The masses of [people] live with their backs constantly against the wall. They are the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed,” wrote Thurman.

In his view, the people with the fewest material resources, the fewest rights and the most obstacles in society constituted the disinherited class.

More affluent and enfranchised Christians ought to intentionally seek ways to develop deep relationships and authentic interactions with the disinherited.

How does this happen?

For me, it came through teaching in public schools.

My rural school in the Deep South was more than 95 percent Black, and 85 percent qualified for free or reduced lunch, a federal measure of student poverty. I came face to face with the problems caused by underfunded and segregated school systems. The surrounding community had almost double the national rate of families living at or below the poverty line. This meant the parents, siblings and extended family of my students frequently faced unemployment, poor health care and higher rates of incarceration.

Firsthand experience with disinherited people changed my perspective on politics.

No longer was it about red or blue but about right and wrong. It wasn’t about keeping power but deploying that power for justice. In our current political morass, we need to constantly remind ourselves that Christians, and their politics, should bring relief and flourishing to those whom the world counts as the least.

Maintaining a focus on the disinherited might give Christians a common starting point to discuss political issues.

If the topic is criminal justice reform, then the conversation can’t just be about punishing the guilty. We also have to talk about honoring the image of God even among the accused and incarcerated. If the subject is health care, then the focus can’t simply be on the amount of taxes we pay. We have to find ways for the poorest people to obtain the best possible service. If the matter is immigration, then discussions can’t solely focus on protecting our borders. We have to think about ensuring safety for both our nation and those who seek to enter it.

This does not mean that all our policy solutions will match. A view of politics from the standpoint of the least powerful will still lead people to different political stances.

But perhaps if more Christians kept the disinherited and their well-being central in discussions of political power, we could have more fruitful dialogue across partisan divides.

Thurman summed up our obligations to one another in the theme of neighborliness.

“Every man is potentially every other man’s neighbor,” he said. “Neighborliness is nonspatial; it is qualitative.”

As a guiding principle of Christian participation in politics, love of neighbor puts us all in service to one another.

This article originally appeared at RNS.