I ran across an article the other day entitled, Why Don’t We Want to Talk about Slavery? This article got me thinking. While I wholeheartedly agree with the essence of the question posed within the article’s title, I also feel that there are a number of other historic realities within our nation which we avoid discussing for the exact same reasons. Therefore, while slavery and its implications for how our society is structured today, are essential things that we need to address, and in much greater detail, I want to use this article to create some space to explore another racialized catastrophe; one which occurred shortly after slavery was legislatively abolished. This subject matter is hardly ever broached. Indeed, it’s discussed even more infrequently than slavery. Yet, I believe that if our nation is to ever truly excavate the cancerous tumor of racism which lingers within the core of its soul, it is a subject matter that must be thoroughly exegeted.

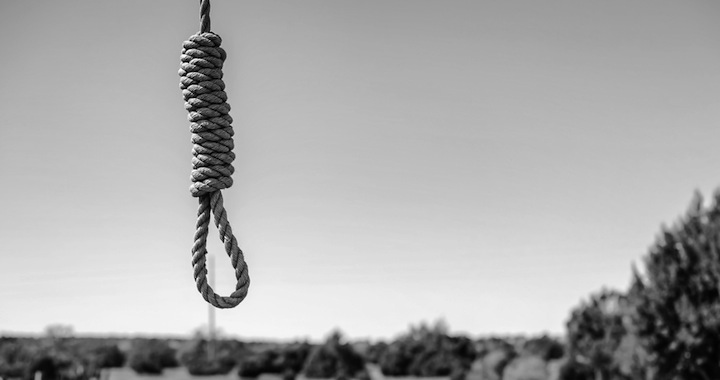

The heinous practice of lynching is both an extremely difficult aspect of our national history and a subject matter that most people quite honestly would rather not deal with. Most citizens know little to nothing about this period of American history. This is because lynching and its horrors are not covered in our nation’s textbooks, nor are they acknowledged—or even lamented—by the broader Church. These unfortunate realities have left the Black Church isolated in its grief over the unnerving reality that during a fifty year period of time, ranging from 1890 to 1940, approximately 5, 500 African Americans were documented as lynch victims. Lynching reached its peak in 1892, shortly after Reconstruction ended, with 155 African Americans lynched in this year alone. This period immediately following Reconstruction became known as the “Nadir Period”[i] of U.S. race relations, after this phrase was coined by Rayford Logan. While it should be noted that African Americans were not the exclusive victims of lynching in the U.S., they were without question the primary prey of this form of vigilante “justice.”

Related: Duck Dynasty, first amendment rights, and Christian values

Moreover, it’s important to note that lynching essentially was not a problem for African Americans prior to emancipation. Because as the following quote from historian Jaqueline Royster indicates, slaves were simply too valuable and profitable to kill.

The lynching of slaves was rare, first and foremost because it would result in a loss of property and profit. Obviously, it was more profitable to sell slaves than to kill them. Second, there was more advantages to planters when slaves were executed within the law, as planters were compensated for their lost “property.” Third, the lynching of slaves served to under-mind the power base of the South’s wealthy, white, landowning aristocracy. In effect, mob violence against slaves would have transferred the power of life and death from the hands of planters to the hands of the mob, whose numbers were quite likely to include non-elite whites, as well. Such a transfer of power would have loosened the systems of control, the general stronghold of the landed aristocrat over both economic and political life. The lynching of African Americans before the Civil War, therefore, was exceptional indeed.[ii]

In fact, during the Nadir Period, the practice of lynching became so prevent and widespread that the Tuskegee Institute, a predominately black institution in Alabama which later became Tuskegee University, decided in 1881 to begin issuing annual reports on lynchings occurring nationwide. Astonishingly, it was not until 1952 that the institution was able to report that there was not a single lynching to report within a given year. Moreover, while popular belief holds that lynching only occurred in the South, this was a national sin, one which the South alone cannot serve as a scapegoated for. While it is true that lynching was particularly prevalent in the South, it was not exclusively a Southern horror, lynchings were enacted as far North and West as Minnesota, Illinois, California, and Oregon. Ironically, Indiana, a state in the heart of the upper Midwest, was one of the states with the highest number of lynch victims.

While the historic legacy of lynching hovers over our nation as a haunting reminder of racism enduring presence, well beyond slavery, there are two reasons why I believe that lynching is an indictment upon the U.S. Church, in particular. The first reason is the broader Church’s appalling silence around the issue during the Nadir Period. With lynching be as commonplace as it was, there is no way that the Church was unaware of this grave injustice being exacted by vigilantes within its communities. Therefore, the Church’s silence on the matter makes it complicit in this national tragedy and thus explicitly suggests that we have a unique role to play in mourning and repenting of this national turpitude. The second linkage between lynching and Christianity, the latter being indelibly connected to the former, is that most lynchings actually occurred on Sunday afternoons, shortly after church services concluded. After Sunday services concluded, these barbaric executions communally served as a sort of perverted social soiree, which were habitually well attended by Christians.

This harsh reality is not only beyond frightening, but it also serves to prove the necessity of beginning this conversation. In fact, many of those believers who were present at lynchings did not consider themselves to be racist, because in their minds the racists were the ones actually conducting the lynching. These individuals would avoid the stigma of racism and the conviction of the Holy Spirit by rationalizing their presence as purely spectators; arguing that they just happened to be present at the scene of the hanging, which in their minds did not make them culpable. Lynchings were routinely photographed and turned into postcards, which would then be used to promote future lynchings.[iii] According to historian Ralph Ginzberg, “lynching [which also frequently included burning, castrating, & disfiguring the victim, ] were spectacles, announced in advance, attended by whites including women and children, and covered on assignment by newspaper reporters in a manner not unlike contemporary coverage of sporting events.”[iv] People would send these postcards to their friends inviting them to attend the next lynching…as if these executions were some sort of theatre at a local country club. The most disturbing part about this spiritually is that people who self-identified as Christians played a significant role in these events, in both the promotion and execution of lynchings.

Theologically, this exists as the most disturbing part of the lynching phenomenon. Believers’ lack of morals and ethical response to God’s love was so nonexistent that it was commonly acceptable within the last one hundred years of this nation to watch someone be tortured, burned, castrated, and killed for sport just because of the color of their skin. Moreover, one’s faith was thought to have nothing to do with coming to the defense of these helpless victims. In fact, one’s faith did not even prohibit Christians from participating as enthusiastic observers within the crowds. Furthermore, it was normative for infants and children to be taken by their parents to see these “spectacle” lynchings. Imagine the psychological trauma of growing up seeing this sort of barbarism on a semi-regular basis. This had to have had a profound impact on these young minds. Being taken to public executions, where African Americans were looked upon as a kind of game animal to be caught and executed for pleasure, had to permanently hallmark the image of black inferiority within the young, impressionable minds of children, not to mention the scarring and damning psychological effect this had to have on the entire African American community who saw family members, friends, and neighbors persecuted with such brutality.

Also by Dominque: What Does Micah 6:8 Really Mean?

Thus, the psychological impact of these pervasively grotesque images cannot be divorced from the diseased racial imagination which exists within our country. The remnants of racism that are expressed within society, many of which have become institutionalized, have to be understood in relation to the reverberating effects of the trauma of the lynching tree. Racism today seeks to hide behind its institutionalized manifestations, which makes the façade of colorblindness a tempting one for many citizens, particularly Christians. Sadly, it is in our inability and unwillingness to authentically talk about, lament over, and repent concerning the historic realities of racism in our nation, which undergirds the existence of this sin within the Church and country today. This article’s not intended to point fingers at particular Christians nor is its intent to cause further division within the Body. Instead, its aim is to open our eyes to this often untold historic reality of barbarism within our nation, to create a space to begin lamenting this reality, and to summon us to begin this conversation as followers of Christ, so that we can begin to heal the wounds which have historically gone untended and consequently unmended.

[i] Nadir means the lowest point; time of greatest depression. For U.S. race relations, this period of time following Reconstruction is identified as the era where racism was worse than any other period in our postbellum nation.

[ii] Jacqueline Jones Royster. Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892-1900 (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1997), 8.

[iii] James Allen. Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America; http://withoutsanctuary.org/.

[iv] Ralph Ginzberg. 100 Years of Lynching (New York, NY: Lancer publishing: 1962), 46. Lynching frequently included ritualized burning at the stake, castration, and mutilation in addition to the victim being hung from a tree.